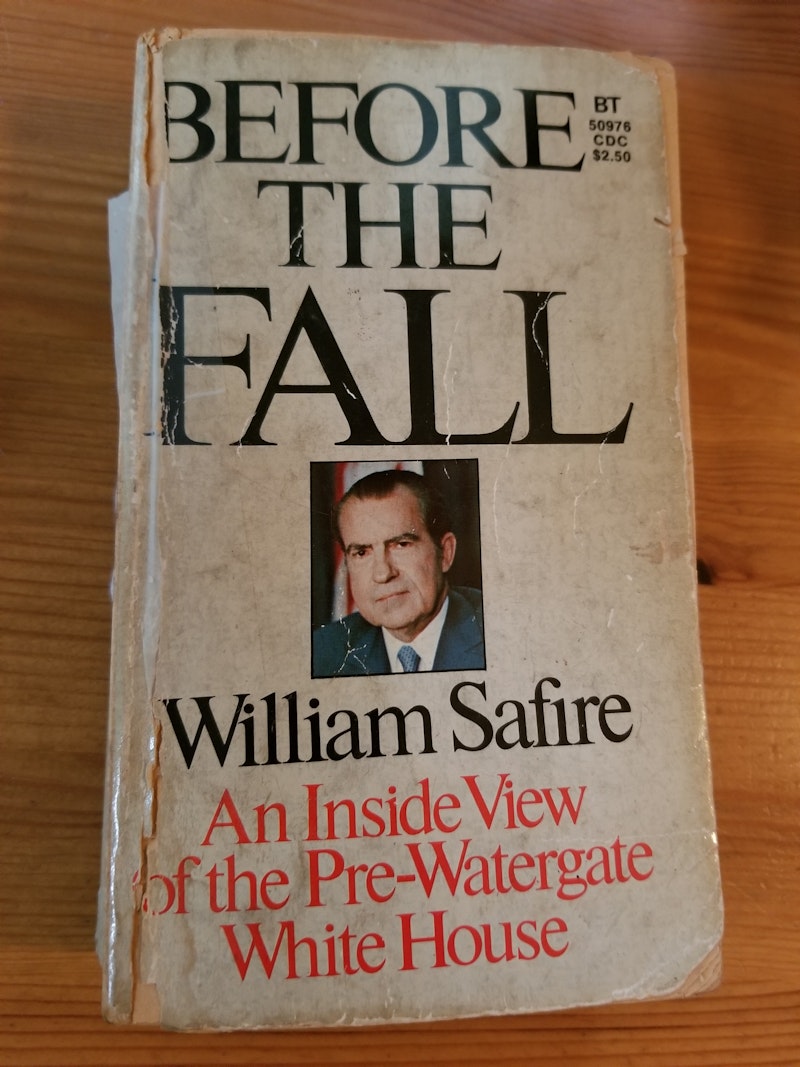

Recently, as talk of impeachment ratcheted up, I reached for my battered copy of William Safire’s Before the Fall: An Inside View of the Pre-Watergate White House. I’d gotten it in 1981 at a used bookstore in Maine while visiting my brother and his friend Bruce Ohr, then college students working as summer caretakers; it so happens this is the same Bruce Ohr who, at the Justice Department decades later, emerged as one of President Trump’s scapegoat nemeses.

I leafed through the yellowing pages of Before the Fall. Safire, who’d worked for Nixon as a speechwriter before becoming a New York Times columnist, presented a complex picture of a president who had genuine virtues alongside serious character flaws; whose crimes and lies were mixed into a career that included earnest and sometimes brilliant efforts in public policy.

Nixon’s “greatest achievement,” Safire wrote, is that “he was in the end what he wanted above all else to be—a peacemaker, which better men who were Presidents often failed to be.” Trump aims for similar status based on his diplomacy with Kim Jong Un, except that unlike Nixon’s dealings with the Soviet Union and China, there’s no substance behind it. Trump just wants a show of making a hostile power less dangerous, regardless of what North Korea does.

Safire wrote that Nixon “patterned himself after Charles de Gaulle, above all others,” a statement that rings true. I recall a reverential chapter about the French statesman in Nixon’s Leaders, and lately was struck by a passage in Julian Jackson’s new biography De Gaulle describing a 1969 meeting in which the newly elected U.S. president “imbibed de Gaulle’s advice almost like a pupil receiving the wisdom of a master.

But if Nixon was no de Gaulle, Trump is certainly no Nixon. Nixon would laugh at Trump; guttural belly laughs fighting against self-containment at the thought that the latter’s defilement of the presidency will enhance the former’s posthumous reputation through comparison.

I live in northern New Jersey, a few miles from where Nixon lived in the 1980s. That house, in the town of Saddle River, has been torn down, having fallen victim to mold under its subsequent owner, a Japanese absentee businessman who delighted in possessing Nixon’s onetime residence but couldn’t be bothered with the details.

There are still some traces of Nixon in the area, though. I enjoy eating at the Ho-Ho-Kus Inn & Tavern, partly because Nixon was known to eat there. At the horseback riding stable at Campgaw Mountain, there’s a plaque signed by President Nixon, opening for recreation what had been a federal site for national defense; antiaircraft missiles were controlled from there.

Nixon had an impact on me in my youth, and so did Safire. In my teens or 20s, I read Nixon’s books The Real War and Leaders; I re-read the latter in translation to improve my Spanish. Safire was a role model for me in his career as a wordsmith, a savvy political analyst and a “libertarian conservative,” the last a label I long used to describe myself before deciding the negative associations of each could no longer be obscured by combining the terms.

I’m a centrist independent now. Trump fills me with cold fury at the thought of what my former party has become, such that I write manifestos proposing a new one. However, as it happens, New Jersey allows independents to switch to a party on primary day. Watching the boomlet of interest in Maryland’s moderate Gov. Larry Hogan, I can imagine myself doing that.

Still, I will never truly be a Republican again. The Trump phenomenon has made me reevaluate not just the party as it is now, but its history. Watergate now looms larger for me as a threat to the rule of law. Back in the 1980s, I could admire G. Gordon Liddy for the fanatical, hand-burning and rat-eating toughness he described in his autobiography Will. Now, someone eager to burglarize and wiretap the opposition party’s offices strikes me as repellent.

Yet I can also see that Nixon, however wrongly he acted in Watergate, at least had some sense of the public interest mixed in with his political self-preservation. He wanted to cover up the campaign lawbreaking so that he could continue his high-level diplomacy. He recorded his Oval Office conversations because he aspired to write great memoirs. He fought against release of the tapes with a genuine concern about the confidentiality of presidential deliberations.

There will be no book like Before the Fall about the Trump presidency. Trump may still have his apologists after whatever is yet to happen, but no one will write of him in the vein of this Safire passage: “The dismaying truth to those who know Nixon is that underneath the imitation-oak-grained formica veneer is solid oak, beneath that phony image of character is character.”

And despite Trump’s impulsivity, there will be no scene like that of May 1970 when a sleepless Nixon, in the dead of night, spontaneously went to the Lincoln Memorial and met student protestors who were camped there, this at the height of antiwar upheaval just days after the Kent State shootings. He conversed with them about pacifism, environmentalism, the plight of minorities in America and “the spiritual hunger that all of us have.” He encouraged them to travel, advising an architecture student to visit the Soviet cities of Novosibirsk and Samarkand. He spoke and listened on many subjects, and it wasn’t all about him.

—Kenneth Silber is author of In DeWitt’s Footsteps: Seeing History on the Erie Canal and is on Twitter: @kennethsilber