Millions of Americans have laughed at Donald Trump since last summer. He's easy to write off as a dilettante spoiler or just a clown, but he’s still competing for the presidency. We see that he's a fast learner and his numbers continue to grow like crabgrass. How does he do it? There’s modern precedent for a candidate like Trump and it's within living memory: George C. Wallace. Wallace would’ve recognized Trump's act as what he called Backlash Politics. Populism at its worst.

Wallace began his political life as a representative in the Alabama House of Representatives and then as a circuit court judge. Interestingly, in this early period Wallace was a fair man. By early 1950s Alabama standards he was pushing liberal. There wasn't a moment in his day that was unplanned or otherwise directed towards his broader goal of becoming someone important. His moderate stance on race was the practical acknowledgment of a young politician that everyone was a potential vote. Wallace even volunteered for a seat on the Tuskegee board that he hoped to parlay into black support for a gubernatorial run. He got his chance in the 1958 Alabama governor's race. Wallace ran a straightforward but aggressive grassroots campaign focusing on issues that cut across race like paving roads and building schools. He avoided race on the stump and the NAACP endorse him. His opponent, Attorney General John Patterson, by contrast, campaigned openly with the KKK.

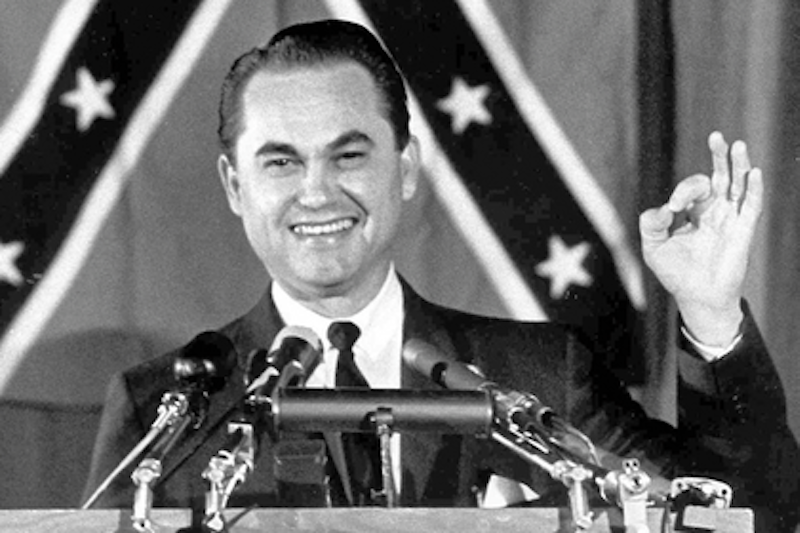

Wallace lost. He took from his defeat the hard lesson that segregation of the races was the animating force of the white voters of Alabama. Due to the obstacles placed in its way the black vote barely figured into the final tally. The way to victory was clear: the shortest distance between Wallace and the governor's mansion was the low road. Wallace became a meaner man, preaching hard line segregation. He won in ’62. “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, segregation forever” were the words that became his trademark. It didn't matter that he ultimately failed in his segregationist agenda. The South was conditioned to losing. His national moment came when he defiantly blocked the entrance to the University of Alabama’s registrar's office. It didn't matter to his supporters that Wallace's moment was an orchestrated one. He’d stood up to the Northeast establishment.

Testing the waters, Wallace enters a few presidential primaries in the1964 presidential race and proved his popularity wasn’t restricted to the South. The Northeast establishment viewed him as a pesky mosquito but, like Trump, he was building a base that couldn't be ignored. The enemies were always outside agitators such as Martin Luther King and his Pro-Communists or the pinko anarchists running Washington. According to Wallace’s recipe for a simple world, most problems could be addressed by kicking hippie ass and maintaining a strong law and order society.

I saw Wallace once at a campaign rally in Columbia, Maryland during his ’68 presidential campaign. Conceived by James Rouse as a planned community in the forefront of a racially harmonious future, Columbia was intentionally laid out in a jumbled sort of way to minimize regimentation or division. This was urban planning as 1960s social activism. Trees, common spaces and gently undulating hills would conspire to create an egalitarian commons for all to enjoy. If income is any indication, Columbia now sits in the second wealthiest county in America. Columbia at that time, however, was still little more than construction equipment. The promise of the future was still a ways off as evidenced by Wallace being one of the opening “shows” at the newly finished Merriweather Post Pavilion. I'd like to say this was some kind of “Stand By Me” coming of age moment for me—I was 15—but the whole thing was so dull I barely remember being there. As a goof I’d tagged along with the older boys to see what all the fuss was about. Just the name Wallace could raise goose pimples on your neck.

Expecting a firestorm, what Wallace delivered was closer to a country revival. The audience fanned itself lazily under the new pavilion in the August heat as black teens worked the aisles with red, white and blue donation buckets. I don't remember him mentioning anything about race. This could have been out of sensitivity, considering the Baltimore riots had happened only months before after Martin Luther King’s assassination. But that’s unlikely. Sensitivity was never Wallace's strong suit. He paced back and forth on stage, working himself up over a recent brush he’d had with the Northeast press. He kept spitting the word “recapitulate” out like it tasted bad in his mouth. I had no idea what he was getting at but Ted Cruz would appreciate this as a proper New York values moment.

You could tell from the grunts, nods and mumbling that Wallace was getting through. The crowd was mostly older rural farmers with their wives. I don't recall many kids. As a kid myself I felt no connection with Wallace. I was part of another world. My suburban way of life was on the ascent while the rural way these folks represented was on the wane. In a few years everything would be changed: paved over forever by tract home subdivisions and the strip malls of modern Howard County. These people may not have been able to articulate their future but they felt the shadow of change already casting itself over their world. In the meantime, for these God-fearing Wallace supporters it all boiled down to blaming the hippies, voting out the communists, and standing up for law and order.

Look at George Wallace’s 1968 campaign to understand the appeal of Trump and Cruz today.