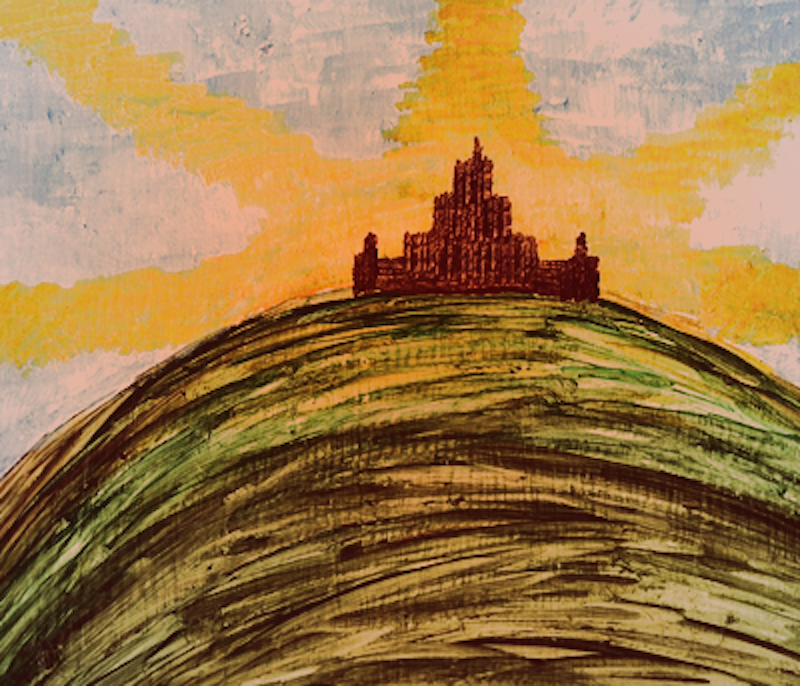

When I was a child my grandfather told me that our country was special. He said that it became that way because brave men studied, and fought, and killed for the idea of a nation that would always stand against tyranny, and in defense of human rights that were and remain universal, and for a long time I believed him. Why wouldn’t I? The people of this nation might disagree on important issues but we’d always keep improving. No matter our differences, we were a united people and that bond was permanent, and ultimately we’d never do anything but move our country forward to a better future. Our nation was extraordinary, right?

In February, voters in Iowa and New Hampshire will begin the process of selecting our next president. Conventional wisdom says that Hillary Clinton will emerge from a vast field of three to win the Democratic nomination she’s been seeking for almost a decade. On the Republican side, the smart money indicates that while the primaries will be a wild, grueling, unpredictable affair, eventually the candidates will begin to whittle down and, despite Donald Trump’s monstrous fame, name recognition, and legion of supporters, the party will coalesce around a traditionally conservative politician like Sen. Ted Cruz. A Clinton/Cruz race for the presidency may or may not be inevitable, but in the end whoever ultimately represents the two parties matters little. Regardless of how the cycle plays out, the country is unlikely to be better off from it.

Just a few hundred thousand Americans from two states that are well over 90 percent white will start deciding next month which candidates are solidified as the frontrunners from each party. After unwillingly submitting themselves to months of relentless advertising and pandering, the people of Iowa and New Hampshire will cast their votes for whichever candidate that has adequately inspired or frightened them the most, but most likely they’ll vote for whatever candidate promises to do the most for them personally. Voters in New Hampshire, one of the wealthiest and safest states in the country, will do what they always do and demand promises of lower taxes and a president who’ll pledge to be tough on crime, but they’ll never actually raise the issues that burden the lives of the poorest and most vulnerable in our country. Why would they, these are issues that largely affect other states far more than theirs.

Over in Iowa, voters will demand solutions to the important issues that affect their lives on a daily basis, like the looming, inevitable threat of radical Islamic terror, or how big to build a wall on the Southern border, but like New Hampshire, neither state will ever challenge candidates to answer questions about fairness or demand solutions to the wars we fight at home. They won’t talk about inner city violence, or about the consequences of continuing the War on Drugs. They won’t ask what ever happened to their right to privacy, or the virtue of an increasingly militarized police state. Voters in these two states will remain as content they’ve ever been, smug and satisfied in the wildly disproportionate attention they get from candidates, all the while extolling the value only they can see in the permanence of their commitment to the democratic process. Other people’s problems will remain other people’s problems, as they always have.

And that’s fine. I don’t really expect someone from Iowa or New Hampshire to care about my state, much less my city, but the shared values of Iowa and New Hampshire become mine and yours when the votes they cast provide an immediate advantage to candidates seeking our highest office, to those who want the power to decide on the quality of my drinking water, the fairness of our tax code, or what countries we go to war with. Their votes help decide who controls the strongest military in known existence, the future of space travel, the direction of our planet itself, but their votes matter much more than mine, and so with it do their values and concerns. My city (Baltimore) and I are left with no other choice but to put our faith in the virtue of the process as determined by the Constitution, and in the wisdom of our citizens. We trust that two competitive races will result in two candidates that offer two genuine if conflicting plans to move our country forward, but what do we really get?

I was raised to believe that my country was exceptional, but I have seen little evidence of this in my lifetime. The small faith I once may have had in the ability of the people of the United States to know good from bad and better from worse has gone from some to none as a result of seeing how our nation has reacted to the early phases of this primary process. I’ve sat by and watched in all-out wonder as Republican primary voters stood up for the ideals they hold so dear and speak so often and so loudly about.

I watch as they stand up to defend traditional, Christian-based values like how good it is for our country to permanently abandon starving refugees from a war-torn country in exchange for an unknowable, incrementally small increase in safety. I see Republicans fight to defend the right to religious liberty at any cost, but only for some, and definitely not for Muslims, yet with a faith that the government they despise can somehow become wise enough to tell which religion to oppress from all the others. I watch as Republicans scream in favor of proud, conservative principles like a government large enough to defend its citizens from every threat imaginable and capable of marching door-to-door-to-door to deport every single person in the country here illegally, but at the same time, small.

Yet for all the self-indulgent rhetoric and incompatible ideals exposed during the Republican primary, the Democratic primary has been arguably worse. While Democratic candidates have surely been more reasonable and measured on the campaign trail, and their polices less xenophobic and heartless, for all the faults you can find with the Republican Party the winner of their contest will be one decided by the voters, not the party itself, and not by insiders looking to circle their wagons around a presumably safe frontrunner. Republicans don’t limit their debates to a tiny handful, nor schedule them on weekends in a vain effort to shield the candidate they presume to be most electable from being attacked on national television by another candidate in their own party. Say what you want about the GOP, but their winner will be battle-hardened and the party will rally around him, and the Democrats will be left with the candidate that other people decided was best for them, and because of this the voters will never love that person. Like a table with two legs the Democrats have decided to stand for nothing, and we’re all worse for it.

If you’re like me and can’t bring yourself to truly identify with either major party, all we can do is watch it all happen from the outside. We watch two parties indulge their worst impulses and wait to see what two choices are left for us to choose from on Election Day. We let tiny people in tiny cities and tiny towns fight over how they choose to define our country for us. We sit by and wait to see what happens when a country that prides itself on its exceptionalism chooses not to be any longer, and there’s nothing we can do about it.

So who failed whom? Did the Founders fail us or did we fail the Founders? Surely they never could’ve predicted that one day our nation would willingly choose to allow the principles of reality television to become the qualities we choose to define our nation by. In the end we chose to fail ourselves. So if the question is what two candidates will eventually emerge from the field and run against each other in the fall of 2016, what does it really matter if getting there means appealing to every American’s shittiest version of themselves? I’d never expect Iowa or New Hampshire to care about the city I live in but I expect my country to. I expect that the suffering and dying that happens so close to my home to matter to someone, but it never does. I’m left with the realization that we will never be the nation I wish it could be, and my grandfather isn’t around any longer to convince me otherwise.