One night in April of 1998 there was a raucous party taking place in the ballroom of Manhattan’s historic Puck Building, the occasion of which was a celebration of the weekly newspaper New York Press’ 10th anniversary. The space was filled to fire-code capacity almost immediately at six p.m., and throughout the night, over 1500 people jammed inside, taking advantage of an open bar, the then-trendy cocktails passed around by representatives of some vodka company and the company of an incongruous and unmistakably jolly crowd. In one corner, men in suits conversed quietly; in another, lines of cocaine were snorted out in the open. Outside the Puck Bldg., mostly in the back, pools of vomit gave proof that it was a very successful affair.

As it happens, I was the proprietor of New York Press (which I founded in ’88 and sold in ’02), so my memories of that evening—a period when the paper was firing bullets every single week and distributed some 125,000 copies each Tuesday—are quite clear. More so as I write this, two days after learning the sad news of the prolific and influential journalist Alexander Cockburn’s death, felled by cancer at the age of 71. Early on July 21, not long after Cockburn’s partner at the website CounterPunch, Jeffrey St. Clair, announced his friend and collaborator’s passing, Twitter was pulsating with reminiscences and condolences (my long-ago colleague at Washington’s City Paper, Jack Shafer, provided an invaluable service of linking to numerous Cockburn articles), as well as a few tasteless jabs, such as “the world is a cleaner place.”

At one point during that evening in ’98, there was a scrum of journalists and artists a few feet from a bar, and Cockburn was the center of attention, and judging by his Jack Nicholson-like smile he didn’t mind at all. I’d hired Cockburn as a weekly columnist in ’96, not long after his former employer, The Village Voice, had abandoned paid circulation, and had my travel agent book him a redeye flight from his home in California to attend the festivities. So, as Alex was boisterously holding forth on topics both current and arcane, there were people roaming in and out, such as Rick Hertzberg, John Fund, Chris Caldwell, John Strausbaugh, Sam Sifton, Robert Messenger, Bill Monahan, Tony Millionaire, Michael Gentile, Jonathan Ames, Danny Hellman, Mike Doughty, Jim Knipfel, Alan Cabal and J.R. Taylor, to name just a handful. It was a different era, of course, a time when writers and artists of varying political views could carry on heated, impassioned debates and still have a laugh when the contretemps was exhausted.

An hour or so later, as my wife and I were keeping an eye on our two boys, toddlers at the time who were creating havoc at the dessert table, Alex waxed nostalgically about Ireland, where he grew up, and invited us to spend a week or two that summer at a friend’s castle not far from Cork. It wasn’t the beer talking—at that point in his life, he didn’t drink much—but a sincere offer, and although we didn’t take him up on it, it was greatly appreciated.

Alex, who wrote his NYP column for five or six years (writing with his “radical” perspective, he was brutal about Bill Clinton, loved Hillary, and hated Gore, and wasn’t kind to liberal media darlings such as Michael Moore and Eric Alterman), wasn’t the easiest writer to deal with. It wasn’t that he was contentious, but rather his habit of pushing deadlines to the last minute, and the enormous amount of work that the paper’s extraordinary copy editor, Lisa Kearns, had to shoulder. Sure, Sifton, Strausbaugh and I all read and lightly edited Alex’s column, but it was Lisa who did the heavy lifting, going back and forth with him over the phone about 50 different facts. It wasn’t pleasant, although, as she told me the other day, she remembered that he was a “character.” On occasion, at least during the first year he contributed to NYP, Alex would lapse into the British custom of double-dipping; passing off a piece as original when it was published in another publication a few days earlier. Lisa, without the benefit of today’s technology, would trip him up, saying, “Alex, this ran in a Glasgow paper a few days ago, so get me something else.” Which he always did, mainly because he was chronically short of cash, and needed the paycheck.

Years later, I’d keep up with Alex’s monthly column in The Nation (he valued that paycheck too, for he seldom had kind words about his fellow contributors there, and I’ll just leave it at that) and CounterPunch. We’d email every other month or so, just to say hello and discuss current political and media news. We didn’t agree on much, but he was unfailingly polite, asking about my family and, until recently (like almost everyone, I hadn’t known he was ill) saying we should get together in California.

Alex Cockburn was a journalist who broke media criticism barriers at the Voice in the 1970s (as a college student, I read his “Press Clips” column first, and then James Wolcott’s “Medium Cool”), pissed off almost everyone at one time or another, had more enemies than there were names in the 1980 Manhattan White Pages, and reveled in it all.

In my opinion, he was one of the greats.

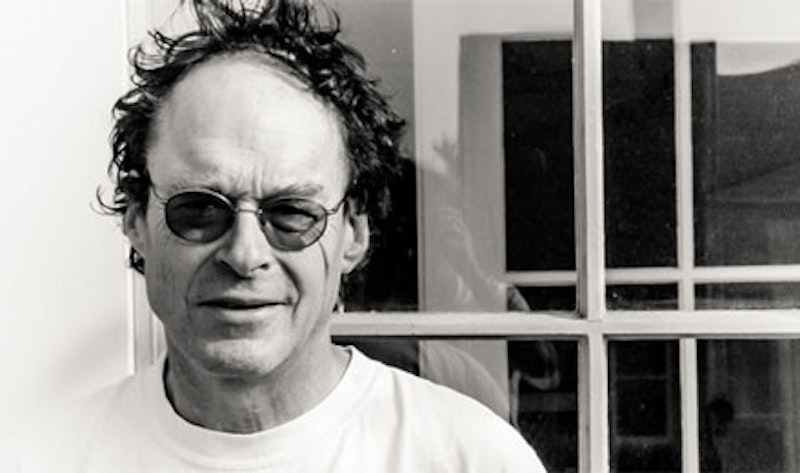

Alexander Cockburn as Mensch

The late journalist’s bite wasn’t always worse than his bark.