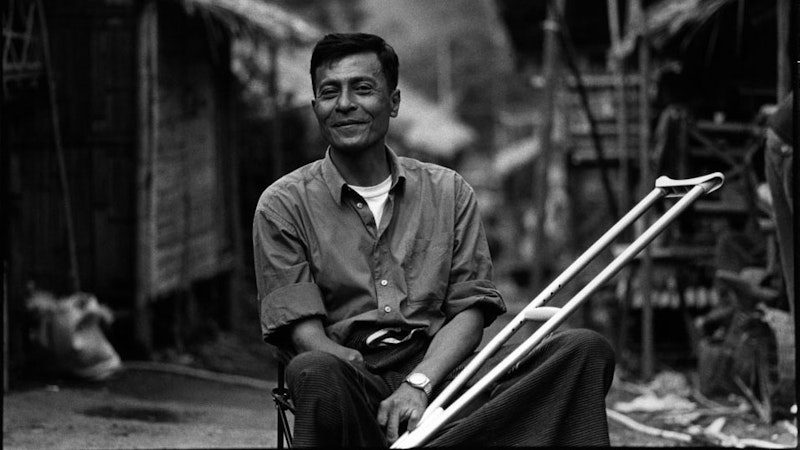

I recently watched the excellent HBO documentary Burma Soldier about Myo Myint, a heroic dissident who left the Burmese army to fight against his country’s evil system. It is a terrifying story—the man was arrested, tortured and locked up in solitary confinement for years by a brutal military dictatorship. He has one leg, one arm and three deformed fingers. At the end of the film Myint moves to America to join his family, who emigrated over a decade earlier. The civilized nature of our free society made America look like the antithesis of Burma’s regime. At the time I couldn’t help but contemplate the irony of how America’s policies—which have been rooted in imperialism and given rise to countless regimes as ruthless as Burma’s—completely contrasts with that picture. The scope of America’s empire is almost worldwide and deeply ingrained in our culture. Stephen Kinzer’s Overthrow, America’s Century of Regime Change from Hawaii to Iraq offers a nice outline of how this has played out during the past century.

Kinzer’s description of life in Guatemala after the United States organized a military coup to overthrow the democratically elected government of Jacobo Arbenz in 1954 and impose a military dictatorship favorable to American corporate interests describes the situation in Burma today, as depicted in Burma Soldier: “death squads roamed with impunity, chasing down and murdering politicians, union organizers, student activists, and peasant leaders. Thousands of people were kidnapped… Many were tortured to death on military bases. In the countryside, soldiers rampaged through villages, massacring Mayan Indians by the hundreds.” Kinzer adds that “This repression raged for three decades, and during that period, soldiers killed more civilians in Guatemala than in the rest of the hemisphere combined.” Throughout, “the United States provided Guatemala with hundreds of millions of dollars in military aid.” Furthermore, “Americans trained and armed the Guatemalan army and police… and dispatched planes from the Panama Canal Zone to drop napalm on suspected guerrilla hideouts.”

Such behavior is standard practice for U.S. policy makers. Chile’s September 11th took place in 1973, when President Richard Nixon orchestrated a coup to oust the democratically elected President Salvador Allende from power and install Augusto Pinochet. “The main concern in Chile,” Nixon explained in a cabinet meeting according to declassified internal documents, “is that [Allende] can consolidate himself, and the picture projected to the world will be his success… If we let the potential leaders in South America think they can move like Chile and have it both ways, we will be in trouble.” This describes the domino theory, which has long been a cornerstone of U.S. policy. Of significant importance is the fact that two American corporations, Kennecott and Anaconda, had dominated Chile’s economy for a long time through its monopoly over the copper industry. Allende sought to redistribute the wealth and land of Chile to bring greater equality and prosperity to his poverty stricken people, which would have crushed the two multinational’s stranglehold.

Kinzer’s book details how this pattern has recurred over and over throughout the last century. To cite a few more examples, he traces the origins of American regime change to 1893, when the U.S. took over Hawaii to maintain corporate control over the country. A few years later American rule replaced the Spanish Empire in Cuba, Puerto Rico and the Philippines. Cuban rebels had been on the brink of overthrowing their Spanish occupiers when the United States intervened and further plunged the country into 60 years of brutal rule. In 1911, Sam Zemurray, the most powerful banana planter in Central America and owner of United Fruit, paid for the United States Navy and a band of rebels to stage a military coup to depose a threatening new government in Honduras.

Turning to the Middle East, in 1953 the CIA got rid of the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh of Iran because he sought to nationalize the country’s oil and bring wealth to his people instead of the British multinational Anglo-Iranian Oil Company. In his place the U.S. installed the Shah, Reza Pahlavi, who ruled with ruthless repression for over 25 years. During the 1960s the CIA played a prominent role in Saddam Hussein’s rise to power, and in 2003, long after Saddam had fallen out of favor because he misunderstood orders and invaded Kuwait (according to Kinzer), President Bush’s invasion was significantly influenced by Bechtel, Carlyle Group, Halliburton, Lockheed Martin, Boeing and McDonnell-Douglas, all of whom were major contributors to Bush’s campaign and profited tremendously from the Iraq war. Similarly, the United States supported the Taliban until September 2001 largely because “an American oil company, Unocal, wanted to build a $2 billion pipeline to carry natural gas from the rich fields of Turkmenistan to booming Pakistan,” and “the pipeline would have to run across Afghanistan.” Ultimately the administration determined it would be better to guard the pipelines through occupation.

Kinzer argues that nearly every overthrow was motivated by a combination of corporate influence and official state dogma—first manifest destiny, then the baseless fear of “international communism” along with the drug war, and now the “war on terror.” It ultimately amounts to imperialism, primarily in the form of proxy governments in client states, but sometimes, as in the Philippines, Vietnam and now Iraq and Afghanistan, in the form of military occupation. There are always strategic interests and/or valuable resources involved: projecting American power, sending messages to reformist-minded governments, establishing U.S. military bases, securing markets for copper, bananas, and of course oil.

Aside from the tragic and evil nature of all these endeavors, they have proven harmful to America. Although there were short-term benefits, state and corporate power threaten to destroy civilization in the form of global warming or nuclear apocalypse, to name two examples. The coup in Guatemala radicalized reformers by teaching them that in order to attain real freedom from imperialism, their revolutions must completely overthrow all existing institutions once they come to power because Arbenz had tried to merely reshape the system for years before the Eisenhower administration, led by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, had enough.

“Cuba is not Guatemala!” Castro declared, when after initially attempting to reform Cuba through the political system he turned to revolution and defied American power, causing the U.S. to try and overthrow his regime numerous times and subjected Cuba to decades of economic warfare and state terrorism. The history of American imperialism explains the otherwise inexplicable continuation of the “Cold War” hostility towards Cuba, just as it explains the obsession with Hugo Chavez in Venezuela. Many countries in the hemisphere, such as Guatemala and Nicaragua, have never recovered from the chaos and plunder that ensued when America intervened. In Guatemala, half the population currently lives in dire poverty, and foreign corporations continue to dominate.

In the Middle East, the consequences of imperialism have harmed American civilians. The Iranian hostage crisis came about because Iranians feared the U.S. diplomats in their country would sabotage the revolution, as had happened so many times before. More broadly, Iranians remain bitter about the overthrow of Mossadegh, and across the Middles East Muslims burn for revenge because their countries are run by oppressive U.S. clients, from Iraq to Saudi Arabia to Egypt. Bin Laden and the hijackers of 9/11 were reacting to U.S. foreign policy, particularly the first President Bush’s installment of a military base in Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War. Those who consider this outlandish need only ask themselves how they would react if Iran set up military bases in America and imposed a military dictatorship here.

Naturally, the common people don't want war: not in Russia, England, America or Germany. That is understood. But after all, it is the leaders of the country who determine policy, and it is always a simple matter to drag the people along, whether it is a democracy, or a fascist dictatorship, or a parliament, or a communist dictatorship. Voice or no voice, the people can always be brought to the bidding of the leaders. That is easy. All you have to do is to tell them they are being attacked, and denounce the pacifists for lack of patriotism and exposing the country to danger. It works the same in any country.

But as a democracy, we have the power to stop our government’s aggressive policies if we can transcend propaganda, organize and demand reform. The imperial project has reached new heights since 9/11. We currently live in a permanent war economy, with occupation occurring in Iraq, Afghanistan, and now Libya (to a lesser extent for the time being). The consequences have been awful for our subjects and us. In addition to the steady erosion of civil liberties, we borrow over $2 billion every day to fund campaigns we cannot afford and deprive ourselves of badly needed resources to repair our crumbling infrastructure and kick-start a depressed economy. After watching the HBO film about Myo Myint’s heroic struggle to free Burma from oppression, I attained a sharper sense of responsibility—if he could find the courage to resist his brutal government we, who are lucky enough to live in a free society, must feel a greater sense of responsibility to force our government to end the imperial project.

—Marc Adler blogs at thebloodycrossroads.com