A recent essay on The Baffler's website has caused a stir on Twitter: in "Childhood's End," Natasha Vargas-Cooper examines the cultural touchstones that she believes signify a newly permanent state of infantilization in young adults. There's something to her argument, but I think her examples are too superficial to really make a case.

Vargas-Cooper opens by lamenting the existence of little boys with mohawks, citing a schoolteacher friend who notes that students with such haircuts are usually the rowdiest. Her ire is really reserved for the parents, suggesting that by giving their sons the haircut of countercultures past, they're trying in vain to relive their rebellious youth. She revisits this idea when talking about the teenage girls who attack the dress codes that frown on skimpy clothing, where parents ally themselves with their daughters against what’s perceived as a demand for patriarchal compliance. Frequently citing the work of Neil Postman, Vargas-Cooper resurrects his argument that the work of Judy Blume is forcing kids to grow up too fast, while attacking adults for enjoying Disney films well into adulthood and keeping TV networks in the sitcom business.

While there's a fair point in misguided parents trying to live through their children, I'm not sure the dress code wars are the right example, especially when there's no shortage of sports dads and dance moms. I think the fights over dress codes have more to do with attention-seeking because there’s an obvious solution: uniforms. Vargas-Cooper never proposes this solution. My colleague Noah Berlatsky made the observation that dress codes can be used to target students of color for suspected gang activity, while another person noted that this targeting could also extend to gender non-conforming students. That only reaffirms my suggestion to put kids in uniforms. Besides being cost-effective for parents, it frees up a lot of brain space that can be used for studying. As Barack Obama told Vanity Fair, "You'll see I wear only gray or blue suits. I'm trying to pare down decisions. I don't want to make decisions about what I'm eating or wearing. Because I have too many other decisions to make."

One of the more compelling arguments is in regard to literacy cultivation in children. Vargas-Cooper writes, "...Postman makes the case that as society moves away from a print culture—wherein knowledge is amassed in stages, sequentially, forcing greater levels of rigor, maturity, and comprehension on the reader—and toward mass media, we begin to lose the mechanism for civic life. Indeed, Postman contends that greater literacy is inextricably linked with the core defining traits of adult cognition and discourse..."

I saw a comment on Twitter that this argument is racist and paternalistic. While terrible things have been done in the name of perceived white intellectual superiority, I don't believe that's where Vargas-Cooper is going at all. I see this more in line with psychologist Jean Piaget's stages of cognitive development, particularly the transition to achieving the capacity for operational thought. It's also reminiscent of Ray Bradbury's contention that "You don't have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them." In a society where people are more functionally literate than they’ve ever been, and with more access to information, what we choose to read, if we choose to read anything at all, is what defines us.

Vargas-Cooper goes on to make some strange arguments about young adult literature. She agrees with Postman's curious assault on Judy Blume's work, that "...the idea that 'adolescent literature' is best received when it simulates in theme and language adult literature, and, in particular, when its characters are presented as miniature adults." Blume was, and remains, a popular author among adolescents, especially girls, because she took the concerns of her audience seriously. On topics ranging from emerging sexuality to religious conflict, generations of Blume's readers have found solace and validation. In looking for an example of cultural dumbing down, Vargas-Cooper, though Postman, has chosen an incredibly poor target.

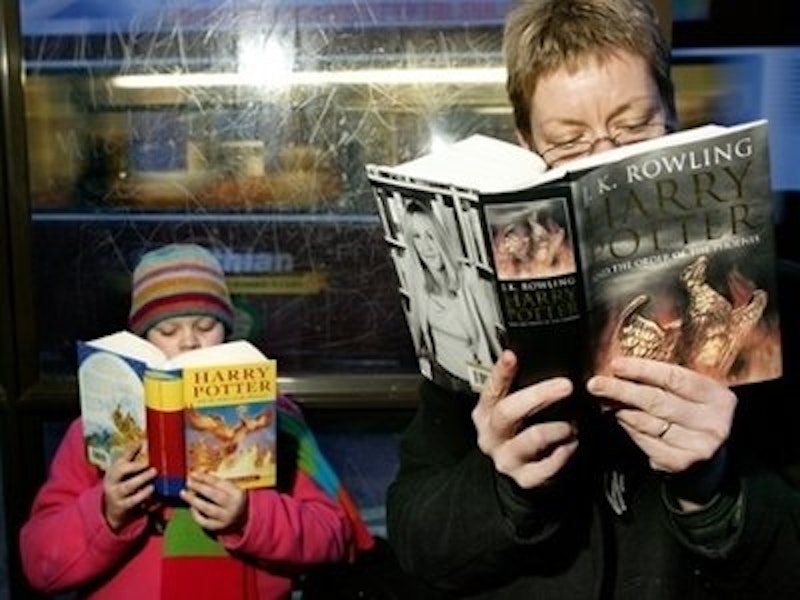

In her attack on adults who read young adult fiction, Vargas-Cooper is unsympathetic to the realities of many adult lives. There are enough educators and parents to justify adults who want to maintain an interest in what the kids are reading. She argues that a generation raised by television has lost the intellectual animus to maintain an interest in more complex literature. There’s maybe some truth in that argument, but to working parents whose time and energy has been stretched thin, it makes sense that serious literature can't always have a prominent place on their to-do lists.

There are some real consequences of this mental exhaustion in adults. As Chris Hedges noted, “We are a culture that has been denied, or has passively given up, the linguistic and intellectual tools to cope with complexity, to separate illusion from reality. We have traded the printed word for the gleaming image. Public rhetoric is designed to be comprehensible to a ten year-old child or an adult with a sixth-grade reading level. Most of us speak at this level, are entertained and think at this level.”

By some measures, Abraham Lincoln spoke at a 10th-grade level. In the 2016 campaign, Donald Trump spoke at a fifth-grade level, while Hillary Clinton spoke at a seventh-grade level and was reviled as an elitist.

Despite Vargas-Cooper's valid concerns, her arguments collapse under the weight of her own snobbery. The regression of our culture and the arrested development of young adults are cause for concern, but she devotes more space to evaluating the consequences than to exploring the economic causes. The closest she gets is lamenting that children are becoming well-trained consumers before they even know what money is. The corporate behemoths that own much of the entertainment and publishing industries are more interested in generating profits than in producing good art. As Hedges noted, the average American worker has been so downsized that they are "no longer making enough money to live with dignity and hope.” Most young adults have student loans to pay off, so they're living with their parents longer, which has its own infantilization. The stresses of contemporary society, from politics to the environment to the economy, can be overwhelming, so it's easy to see why people will want to retreat into nostalgia or vapid silliness. What concerns me most are those in such a permanent state of retreat that they're oblivious to their own dream world.

Piaget encouraged active learning, with children developing problem-solving skills through discovery. I think the lack of discovery has done more damage than television. It's why we're seeing these meltdowns on campus, or why a subculture has emerged to perpetually panic over videogame feminism, or why we seem to be plagued by grown women who speak like teenagers. Many young adults are in a state of existential crisis over their maturity, feeling defeated before they've even begun, but Vargas-Cooper gives too much credit to superficial choices like clothing or movies, and doesn't examine the more substantial structural failures to the developing psyche. What she's looking at is the end result of adults who were raised to be children, and then judging them for acting like kids. If she had aimed her critical eye toward the adults who raised a generation of oversized infants, the support for her argument would’ve been far more compelling.