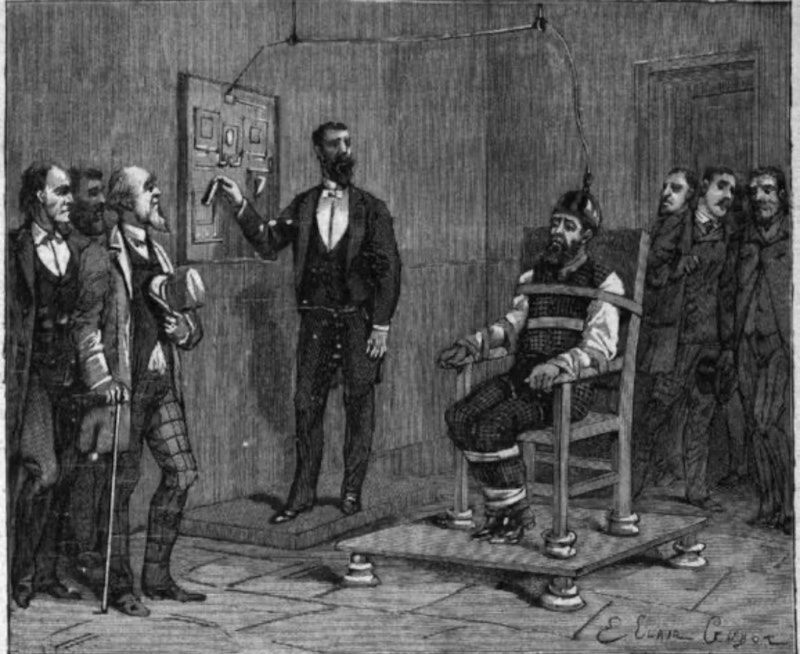

William Kemmler, who was convicted of murdering his common-law wife in Buffalo, didn't want to die in the electric chair, a new invention that had never been tried on a human before. He appealed his death sentence on the basis that it was cruel and unusual punishment, but in May, 1890 the U.S. Supreme Court rejected his challenge. “Punishments are cruel when they involve torture or a lingering death,” the court wrote. But when, 130 years ago today, they pulled the switch on Kemmler in the basement of the Auburn prison facility in upstate New York, his death was a cruel and unusual one by any reasonable standard.

Kemmler, intellectually disabled, was the guinea pig for the beta test of a new killing machine that Thomas Edison had pushed as a more humane alternative to hanging, the traditional American way of executing criminals. It was supposed to be quick and painless. After 17 seconds of 1000-volt AC electric current, a doctor declared Kemmler dead. But Kemmler wasn't dead, so they upped the charge to 2000 volts and zapped him a second time. Kemmler's skin began to bleed. The foul odor of burning flesh filled the room. The witnesses to the execution were traumatized. Eight minutes after the procedure had begun, Kemmler died.

Newspapers called it a “historic bungle” and “disgusting, sickening and inhuman.” Despite its inauspicious, inhumane start, the electric chair quickly caught on. But the glitches never got ironed out. Approximately two percent of U.S. executions by electric chair in the period from 1890 to 2010 were botched.

Convicts who weren't killed by the first power surge have had to wait up to six minutes to receive the second surge. That's how long it took for their bodies to cool down from up to 200° so a doctor could examine them. Syringes have come out of arms, spraying deadly chemicals toward witnesses. Cables have been connected improperly, prolonging the execution to 19 minutes. This is just a small sample of the mishaps that have occurred during state-ordered electrocutions.

If the government asserts it has the right to kill selected citizens, then it needs to proceed with the task with seriousness. But few accomplished people want their names sullied in this way. The government has ended up taking whomever it could get, with predictable results.

How could the Supreme Court have been so confident about a new killing technique not yet supported by any empirical evidence? It's the same confidence that government authorities have exhibited since that time regarding their ability to oversee a humane way to carry out the death penalty. All these years later the evidence is conclusive—that confidence is false confidence.

A guillotine would be a more humane method of execution, but the problem is in the aesthetics. Unlike during the French Revolution, American witnesses to executions don’t want to see heads rolling on the floor. In a sense, the feelings of the spectators trump the pain of the executed party. Some experts believe that the most humane way to execute someone would be to administer a massive dose of barbiturates. Such a death would be virtually painless, but the problem is that this process would be much harder on the witnesses because it takes longer for the prisoner to die. This is the twisted logic that the death penalty invites.

One reason that the horrific deaths caused by the electric chair haven’t had a great impact on society is the perception that people who are suffering deserve it, even though the American Constitution forbids this approach to the death penalty. To some, the slow and torturous deaths are a feature, not a flaw. In 1997, after a fire during an electrocution in Florida, that state’s attorney general warned: “People who wish to commit murder better not be doing it in the state of Florida, because we may have a problem with our electric chair.” While the law-and-order crowd might cheer those words, states that have the death penalty don’t have lower crime or murder rates than states without such laws.

Today the United States is the only remaining Western nation with the death penalty. Since 2018, four inmates have been put to death by the electric chair. After more than a century of trying, this nation has been unable to find a way of killing that is acceptable on the moral and constitutional level. Since the introduction of lethal injection in 1980, the latest "advancement" in execution technology, seven percent of those executions have been botched. It's time to accept the fact that killing someone who’s no longer a threat to society isn’t humane.