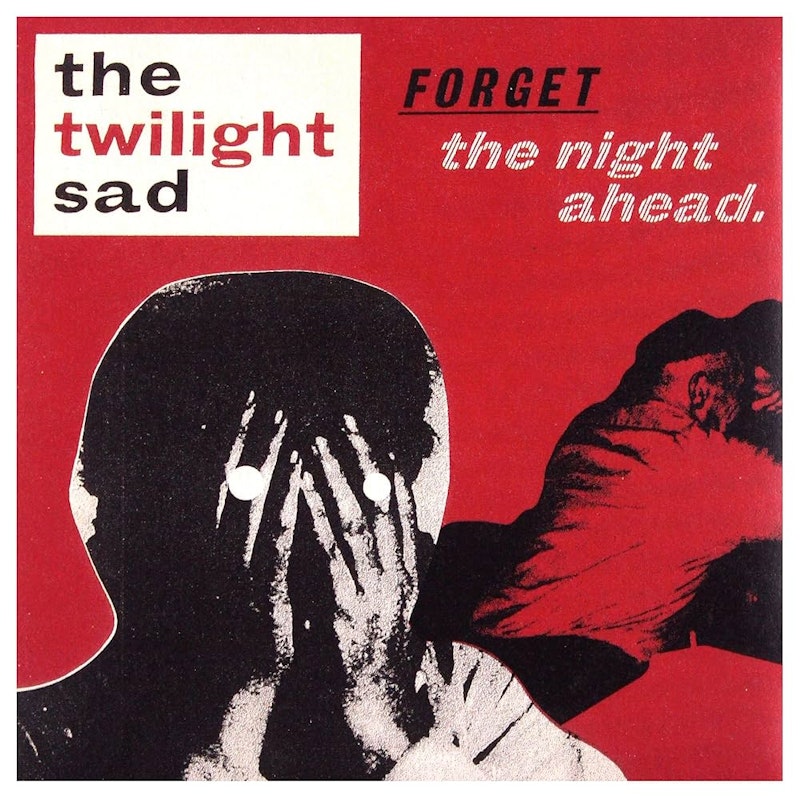

You remember. You remember the girl from India and how she smelled like heaven. You remember the Twilight Sad and their 2008 album Forget the Night Ahead.

You remember 2008 and getting the diagnosis and thinking that you weren’t going to make it. You remember thanking God that if you were going to check out he at least let you be a teenager in the 1980s. You remember that electrifying mix of terror and ecstasy at the thought that you were going to leave this world and find out what comes next.

Those people downstairs

I’m more than a fighter you know

Now it’s 2025. You listen to the new vinyl reissue of Forget the Night Ahead, which commemorates its 15th anniversary. You love this brutal, beautiful record that was like a mirror held up to your battle with cancer. The chemotherapy. The nausea. The girl from India. The Twilight Sad songs were the soundtrack. “I Became a Prostitute.” “Reflection of the Television.” “Made to Disappear.” “The Neighbors Can’t Breathe.”

You’re reading the book The Evil Hours: A Biography of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder by David Morris. “Relationships, when they end, are not unlike car crashes,” Morris writes. “Hidden energies only hinted at in regular motion are violently released, demolishing the carefully constructed bodies we depend on every day.”

You miss the girl from India. What helped Morris is what helps you—literature. Morris: "By reading the stories of Ernest Hemingway, Alice Sebold, Tim O’Brien, and others, survivors are doing more than simply being entertained, they are reifying literature’s essential function: to remind us that we are not alone and in the process demonstrating how trauma was processed by previous generations."

You appreciate that the Twilight Sad, which opened for the Cure recently, was never aping 1980s bands but honoring the dark synth wave of the era while adding something new. There’s that majestic wall of noise like AI meeting Dante. The shredding guitars. The thick brogue and passionate poetry of singer and songwriter James Graham. A storm of what critics called “Scottish Miserabilism.” You think of it more as a terrible beauty. A holy sorrow.

You remember seeing the Twilight Sad at the Black Cat in 2009 and how Graham's defiant pain was your voice in those nights—those nights after chemo, those dark exciting nights pondering mortality and love and heaven and walking around Georgetown late at night. You love the musicality of the Celtic tongue.

Don't frown

Don't frown

'Cause everybody's wearing black clothes

And I'm wearing white

Don't frown

Don't frown

And there's your sister with her answer

And she's always right

You remember Graham on the stage like Christ on the cross, pleading for God, the cleansing blast of the wall of noise. You remember his remarks about Forget the Night Ahead to Pitchfork: “Basically it's about after coming off tour and things like that, getting back into normal life. I don't know how normal it is, but I'll say it anyway. Things happened to me. Lots of people close to me went about crazy, and I don't know how it affected the people around me and everybody else. There were some stories in there. It's a collection of those kind of themes. And it's basically about trying to forget what happened.”

The vinyl reissue is green and black and beautiful and you don’t mind that they changed the color from the first edition, which was red, and which you also have on vinyl.

In The Evil Hours David Morris notes that the Book of Revelation contains a memorable line: “Behold, I make all things new.” Morris: “Every great artistic work is a quiet apocalypse. It tears off the veil of ego, replacing old impressions with new ones that are at once inexorably alien and profoundly meaningful. Great works of art have a unique capacity to arrest the discursive mind, raising it to a level of reality that is more expansive than the egoic dimension we normally inhabit. In this sense, art is the transfiguration of the world.”

Now it's you and I

You and I, you and I know

That it's you and I, you and I

That it's you and I, you and I

That it's you and I, you and I