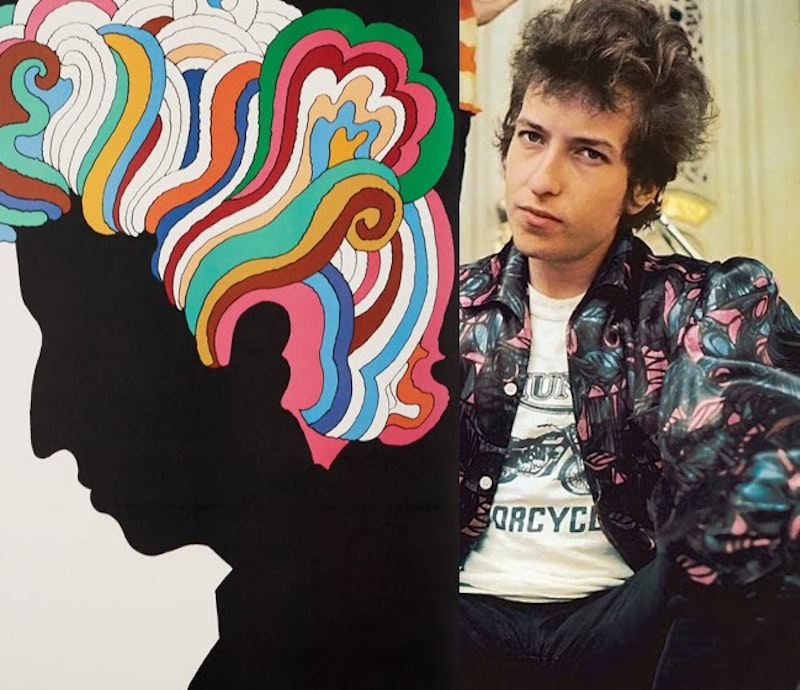

As someone who has an above-average command of the English language, I wince upon seeing in print or screen a word or phrase that’s used so often by lazy writers that it’s meaningless. This isn’t an uncommon complaint, and it’s not really directed at random people who post nonsense—or smart remarks compromised by cliches on social media platforms—but journalists and authors who ought to know better (as well as their editors and headline-writers). Last month, for example, I read a long and mildly interesting essay about the famous designer Milton Glaser (who died in 2020 at 91) by Adam Gopnik in The New Yorker. The story, spurred by the recent release of the anthology Milton Glaser: Pop, has a headline and sub-hed that are so off-putting that I initially gave it a pass: “How the Graphic Designer Milton Made America Cool Again: From the poster that turned Bob Dylan into an icon to the logo that helped revive a flagging city, he gave sharp outlines to the spirit of an age.”

When was America not “cool”?

Anyway, the word in question is “icon.” You could say, “ironically,” that today everyone and everything will be an icon or iconic for 15 minutes. Sunday’s second episode of Succession’s final season was “iconic”; Adam Duvall’s improbable walk-off home run to give the Red Sox a win last Saturday was instantly “iconic”; Dave Grohl and Dolly Parton are “iconic,” or, alternatively, “national treasures”; “Kiss My Grits” Flo, Tucker Carlson, Judge Judy, Tony Bennett, Alex Chilton, Crazy Eddie, Rambo, Michelle Obama, Rachel Maddow, Betty White, Walter Cronkite, Mark Wahlberg, Oprah’s couch and George Will are all icons; and any Super Bowl commercial that’s a success, at least for the advertising agency if not the product, joins the pantheon.

(But Clara Peller was a legit “icon.”)

This isn’t crankiness on my part, but simply an observation about the degradation of publishing today.

Milton Glaser was brilliant and influential: he co-founded New York in 1968 with Clay Felker (and was the design director), a milestone in the magazine business not only for its jaunty and intelligent journalism, but perhaps more importantly the ripple effect it had in cities across the country, which eventually all had their own magazines, although usually monthly. Glaser’s “I Love New York” logo in 1977, and the accompanying jingle really was extraordinary for its uplifting message about the beleaguered “city that never sleeps.” It would take several more years for NYC to recuperate from its fiscal profligacy in the 1960s and 70s, but it gave residents and tourists a hop in their steps. Not dissimilar, say, to the “good vibrations” that would envelop Baltimore in 2023 if the Orioles were to win the World Series; it wouldn’t solve any of the city’s severe problems—violence, flight to the suburbs, incompetent government—but it’d make people, and not just baseball fans, smile for months.

Back to Gopnik’s article. Glaser’s rendering of Dylan, not his best work, was commissioned in 1966 for inclusion in the early-’67 release of Bob Dylan’s Greatest Hits, which Gopnik, 66, stupefyingly calls “seminal,” when it was just a stop-gap money grab by Columbia Records—no new material—while Dylan rested from exhaustion, substance abuse, and non-stop touring in Woodstock. He’s right that the poster was “ubiquitous,” but Dylan was already an “icon,” and I’d say that the cover of his 1965 LP Highway 61 Revisited was/is the everlasting symbol of Dylan’s “cool.” If there’s an LP cover more “iconic” I can’t think of it. Gopnik writes: “It marks the transitional moment, captured in the album, when Dylan’s virtuous folk sermons… ripened into his visionary imagistic anthems. Piety becomes psychedelia in an image of a once well-meaning minstrel whose mind has been newly turned on and tuned in. The poster is not simply of the time. It describes the time, in graphic detail.”

Never mind that Dylan’s early “protest” songs, while partially the earnest lyrics of a 22-year-old (and remember that Dylan’s double-LP Blonde on Blonde was released just after he turned 25), were also a calculated ploy to rise above the 50 or so other folk singers of the time. In 1967, Dylan was not “newly turned on and tuned in”—he was always “tuned in”—but rather escaping the psychedelia and “wear flowers in your hair” counterculture, and recording and writing music (notably “Basement Tapes” songs with The Band) that was the direct opposite of the pop culture ethos of the time, the year of the Monterey Pop Festival, Sgt. Pepper’s, Surrealistic Pillow, Disraeli Gears, Days of Future Passed and Mr. Fantasy. The first example of Dylan’s turnaround came in December of 1967 with the release of the stripped-down John Wesley Harding, which showcased a new voice, lyrics owing more to the Bible than Rimbaud and the (again, calculated) look of a country troubadour.

I was a young teenager in the late-1960s, and loved psychedelia, the start of free-form and often commercial-free FM Radio, Rolling Stone and the records—and so many more—mentioned in the previous paragraph, but while not excessively painful, it’s disappointing to see an accomplished journalist/author like Gopnik erase/distort basic history.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER2023