Leonard Cohen’s back in the zeitgeist. Or, at least, a very specific niche in the zeitgeist. Within a week of each other, Lana Del Rey and the indie supergroup boygenius released new albums with songs referencing Cohen’s 1992 classic “Anthem.” On the Sunday following the boygenius release, the latest episode of the HBO hit Succession featured a character doing karaoke to Cohen’s trite “Famous Blue Raincoat.'' This all might’ve flown under the radar if it hadn’t been for the boygenius song reading as… pretty bad.

“Leonard Cohen once said /‘There's a crack in everything, that's how the light gets in’/And I am not an old man having an existential crisis/At a Buddhist monastery writing horny poetry/But I agree.”

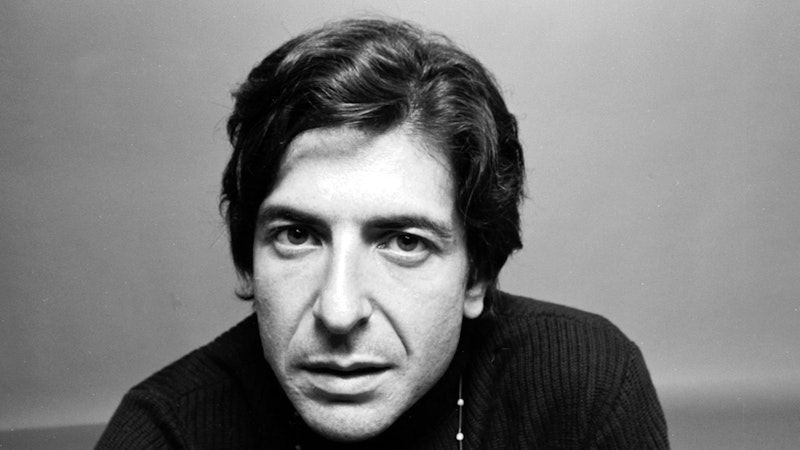

Pedantically we can point out that Cohen wrote “Anthem” a few years before and a lifetime away from going to Mt. Baldy. He was living with actress Rebecca De Mornay at the time, who not just brought Leonard into the star-studded glamor of LA, but also was an instrumental collaborator on the song as well as its hosting album, The Future. It’s notable as one of Cohen’s more openly hopeful songs within his ostensibly bleak discography. “Ring the bells that still can ring/Forget your perfect offering,” Cohen sings like a call to action before affirming that through the cracks, light shines back in, much in the way of the Japanese art of repairing ceramics with lacquer mixed with gold or silver dust to bring a new shine onto once broken things.

Taken out of context as a screenshot on Twitter, the snide tone of the boygenius song seems like both an oversimplification of Cohen and an off-handed misunderstanding or even disinterest in engaging with the artist—it’s indicative of the irony-poisoned self-assuredness that’s popular in counter culture. Moreover, the negative reaction is exacerbated by a lot of people already having their minds made up about the supergroup, seeing it as exemplary of a type of annoying, Doc Martens-wearing kind of indie person. It’s unlikely this crowd would’ve been swayed by an album of any quality, and it’s probably good that it didn’t because, fundamentally, boygenius’ music was never for them anyway. Julian Baker, Phoebe Bridgers, and Lucy Dacus make music personal to themselves that resonate with their audiences, there’s no need to expand beyond that to cater to the ambivalent or apathetic. In the social media saga, the music wasn’t talked about on its own terms, and possibly unfortunately for boygenius, Lana Del Rey had just released her own riff on “Anthem.”

“Kintsugi” comes in as one of the emotionally lowest points of Did You Know That There's A Tunnel Under Ocean Blvd, the last track on the B-side of the album’s first LP. Its elegiac tone mixed with the soft optimism of its chorus repeating “That’s how the light shines in/That’s how the light gets in” is Cohen-esque. Del Rey looks at the “Anthem” in the context of the art her song takes its title from “Think by the third of March, I was cracked open/Finally, the ground was cold, they wouldn't open/Brought by the sunlight of the spirit to pour into me/There's a name for it in Japanese, it's ‘Kintsugi.’”

Del Rey’s often talked about for her use of symbolism and references to film, art, literature and music in her works, and Cohen is possibly underappreciated as an influence even though he’s an artist she has returned to repeatedly, Ocean Blvd possibly the greatest example of this. If “Kintsugi” is reluctantly offering the hope promised in “Anthem,” the final C-side track, “Let The Light In,” is totally giving into it. Featuring (Rockville native) Father John Misty (who I recall in an interview some years ago saying he always wished to fashion himself as an artist after Cohen and also released his own cover of “Anthem” back in 2020) “Let The Light In” is the cracks turning into floodgates, “'Cause I love to love, to love, to love you/I hate to hate, to hate, to hate you/Put the Beatles on, light the candles, go back to bed 'Cause I wanna, wanna, wanna want you/I need to, need to, need to need you/Put the TV on, the flowers in a vase, lie your head.”

It’s a point of evolution, a place she can only arrive to after working through her evolving emotional state, and it’s notable how the lines from the second verse “Look shinin' in the light, therе's so much ridin'/On this life and how we write a lovе song” feel like a reference to her much more painful, almost hopelessly longing track “Love Song” off of Norman Fucking Rockwell. It’s not the first nor the last time she’s done this on Ocean Blvd—“Fingertips” riffs on the melody of “Bartender” and the final song remixes “Venice Bitch,” whose bridge includes Lana referencing Cohen’s second and last novel published in his lifetime, Beautiful Losers (not to mention Cohen does this kind of riffing too, for example in another song from The Future, “Be For Real,” a refrain goes “You see I” before pause, making it feel like he’ll say “I’m your man” and instead saying “I don’t want to be hurt by love again”). Contrasting her current, often controversial, position with the heights of her critical success four years prior, the fears and uncertainties before have given way to a kind of Zen acceptance of circumstance—also Cohen-esque.

This, even in the most generous read, isn’t what the boygenius song “Leonard Cohen” is doing. And it’s not trying to. It’s unfair, in many ways, to qualitatively compare songs with such vastly different goals and intentions. But by happenstance of their nearby releases, this comparison has been forced. I was guilty of this, too, but would like to go back and look at it on its own terms.

“On the on-ramp, you said/’If you love me, you will listen to this song’/And I could tell that you were serious/So I didn't tell you you were driving the wrong way /On the interstate until the song was done,” Dacus opens her song, and, according to a Rolling Stone interview, this really was its genesis, as the trio was riding in Bridgers’ Tesla on one of their writing retreats to work on the album. “You felt like an idiot adding an hour to the drive/But it gave us more time to embarrass ourselves/Tellin' stories we wouldn't tell anyone else.” Whereas the “you” in Dacus’ writing is often ambiguous, usually a lost friend or lover, here it’s clear it’s one of the people sitting right next to her in the recording booth.

“Leonard Cohen” isn’t a bad song, or at least in the way that it’s often derided. Their reference to Cohen isn’t meant to be a grand statement about his personal life’s relation to music; it reads more as off-handed, a riff that a friend makes during a long car ride. When boygenius is riffing, it’s not necessarily with thematic weight the way Del Rey chooses to when she comes back to her old songs. For example, “Cool About It,” a song from earlier in the record plays with the melody from Simon & Garfunkel’s “The Boxer.” Is it trying to draw a thematic link? Maybe, both songs are about trying to push through the punches of life, but what I hear more than anything is people taking an old melody and building something new on top of it. It’s the sounds of a recording session, of someone playing a couple of notes and another getting an idea to add to it. The act of the music-making itself is what’s bonding these people together as much as anything else. “Leonard Cohen,” like the album as a whole I’d argue, is an affirmation between friends. It’s as much about them hashing out their problems together as it is them thanking each other for being there when needed.