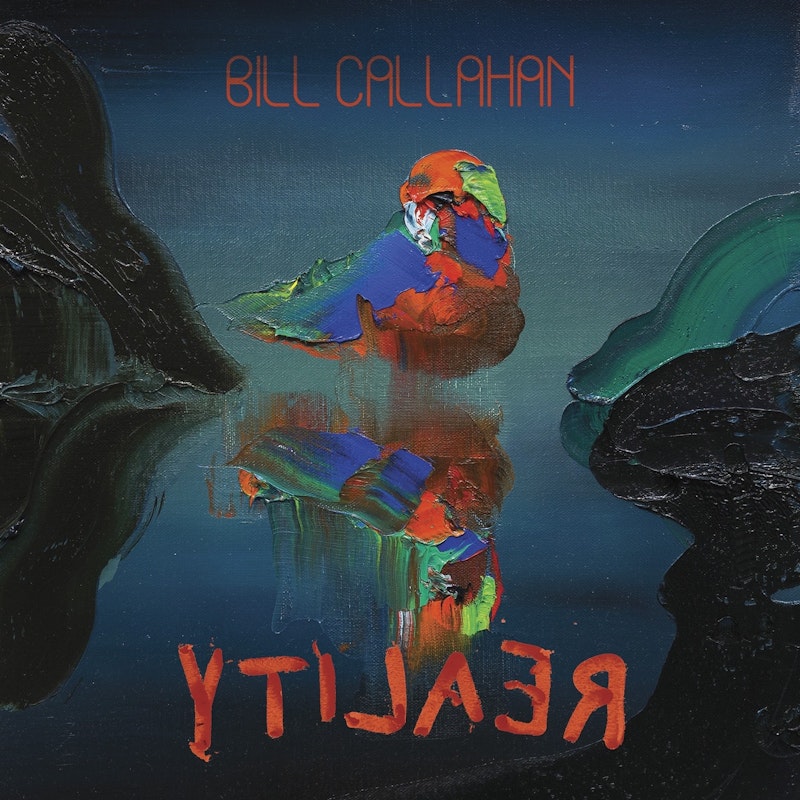

Bill Callahan’s new record is called Ytilaer. Get it? Like Reality spelled backwards? If one of my musician friends called an album Ytilaer, I’d make fun of them incessantly, but the quality and consistency of Callahan’s decades-long discography—under his own name and his earlier nom de plume Smog—engenders a level of trust, not unlike that of a good friend. I’ve even taken to just calling him Bill, the way die-hard Dave Matthews fans will casually refer to him as Dave.

Watching Bill develop from the bratty-voiced avant-garde stylings of early Smog to the tasteful, sage baritone of his most recent records is a little like watching an old drinking buddy get married and start a family: I’m both happy for him and wish he’d get out and cut loose every once in a while. Ytilaer isn’t a bad album, but similar to 2020’s Gold Record, Bill’s newfound calm has possibly neutralized some of the biting observational humor and deadpan wit I associate with his work. Largely absent of these elements, the album’s simultaneously heavier and breezier, more demanding of the casual listener yet also more relaxed than the average Bill Callahan project.

True to its title, Ytilaer takes the natural world as it exists and works backwards. Like much of his music since 2007’s Woke on a Whaleheart (call it his “Christian Name period”), wildlife plays a prominent role on the album, which features birds (“First Bird”), horses (“Everyway”), boll weevils (“Bowevil”), pigs (“Partition”), seagulls (“Lily” and “Drainface”), gators (“Naked Souls”), dogs and coyotes (“Coyotes”). But the overall picture of nature is slightly more stark than what fans of Sometimes I Wish I Were an Eagle might be used to: a mess of “dead or dying seagulls” and “pigs in a pile of shit and bones”; the unending chaos of the solar system condensed to a single “vaguely Hawaiian” hymn; a cold universe in which one must take refuge in the “corpse of a wild horse on the shores of Assateague.”

Simplicity is the theme here, as it has since his 2019 comeback record Shepherd in a Sheepskin Vest. That album occasioned many reviews and profiles about Callahan: Family Man, concluding that his newly-found domesticity had given way to Another Side of Bill Callahan—a gentler, less gloomy, more playful Bill. While he was never a maximalist at any point, his post-Shepherd output is more stripped down, though the content of these songs is no less complex or mysterious for it (I’m still mulling over what “Dreams are thoughts in lotus and chains” means). Which points to one of his unique strengths as a songwriter: despite their simple surfaces and poetic austerity, each song feels like Bill freezing time long enough to explore unexpected entry points—the viscera of a wild horse in “Everyway,” a squeaky gurney wheel in “Lily”—to secrets of the universe.

A recurring subject in his recent discography, songwriting itself takes center stage on one of the album’s strongest tracks, “Natural Information”: “I wrote this song in five/In recovery slides/Using natural information.” The plainness in his delivery belies the strangeness of the lyrics. For instance: “A breeze upon the isle of skin/Meadowlark Lemon lies within.” What exactly does the former clown prince of the Harlem Globetrotters have to do with “a breeze upon the isle of skin?” The reference seems less about Lemon specifically than Lemon as one of many random entries one might visit at Wikipedia, the kind of extraneous information we pursue in the cold reflection of computer screens in lieu of the “natural information” all around us.

That’s just my interpretation, though. One of the hardest things about music criticism, and the main reason I don’t write more of it, is how much more subjective music tends to be than film or literature. The practice of writing criticism demands an amount of precision that’s often difficult to apply to an artform as stubbornly amorphous as music. With that in mind, I appreciate the relatively straightforward folkiness of Ytilaer. However obscurantist, Bill’s songs always leave a trail of bread crumbs to their true substance, demanding no more or less of the listener than he demands of himself as a writer: working backwards.