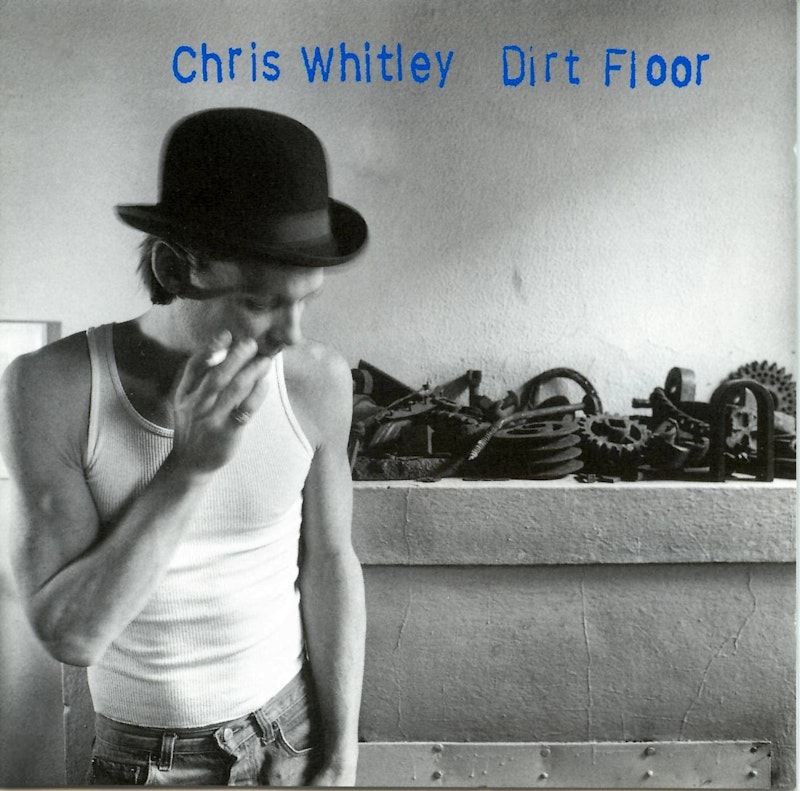

“Wake up running on the sacred ground/Searching the scrapyard for my dirty crown/I’ve been walking a very long time,” Chris Whitley sings on the first song of 1998’s Dirt Floor. The lyrics suggest a dented beauty embedded in a garbage heap of grime and desperation. So does the music. The only accompaniment is Whitley’s tough acoustic guitar, with pained stark notes and slides interrupting his strum like labored breathing. His voice is intimate, veering now into plainspoken almost-talk, now into a falsetto urgency. It sounds like he’s singing to himself, picking through the battered landscape of his mind.

Whitley did just about sing for himself through much of his too-short career. Despite his remarkable guitar-playing and songwriting, he never found a niche. He tried moving to Belgium early in his career and then moved back, experimenting with a stripped-down roots sound, with alterna-rock courtesy of the ubiquitously echoey Daniel Lanois, with mail-order only albums. Nothing really worked. He was only 45 when he died of lung cancer in 2005, respected and admired, but not nearly well-known enough.

Dirt Floor makes it clear why commercial validation was elusive. It’s not an album designed to burn up the charts. Whitley’s inspired by the eccentric sense of time and the use of space in the playing of acoustic blues performers like Charley Patton, Fred McDowell, and Robert Johnson. Generations of rockers have electrified that style, added a full band, smoothed it out, and taken it to the bank.

Whitley, in contrast, uses latter-day recording improvements and a cleaner sound to make his music sound almost harsher and emptier than his sources. Every note slices through a silence, so that even the gently lyrical “Accordingly” is jagged, a serrated lullaby. “If I took her now as the one for me/I could effect a change accordingly,” he muses. It’s like he’s contemplating the virtues of a love song with commercial potential before sending that guitar again on its idiosyncratic, broken path. A faster-paced track like “Ballpeen Hammer,” is a rhythmic battering; as if he’s using his guitar-strings to assault a plaster wall.

The album is only 28 minutes long, and the songs, with their fractured melodies and recursive structures, limp one into the other without much transition—even Springsteen’s lo-fi Nebraska is sweeping in comparison. Whitley’s tracks don’t take you to different places or vistas. They just shift slightly so you’re looking at another mound or depression or abandoned beer bottle in the same empty lot.

One bleak perspective to stare at is “Wild Country,” in which the almost-not-really hook serves as a statement of purpose of sorts.

Breaking rocks all day on the avenue

Gets hard to unearth anything that true

Soon I’m going to drop this jack and run

Returning to the wild where I’m from.

Whitley’s guitar leans into a rough strum which gives the track more propulsion than many of the tunes on Dirt Floor. But there are still rhythmic stalls and notes that fracture the momentum. He’s caught between a longing to escape down the road and the jackhammer in his hand, which leaves the road untraversable. “There’s compromises I can’t comprehend,” he sings, and you watch him follow a path towards no clear destination, all gray shards and loneliness.

The album’s title track comes across, in retrospect, as a kind of epitaph. The pace is funereal, and Whitley’s voice often rises to a kind of yodel, high and windswept. “There’s a dirt floor underneath here/to receive us when changes fail.” Whitley tried various changes, none of which led to commercial success. He kept that dirt floor underneath him though.