Great writing about rock and roll is alive and well.

It’s also 20 years old.

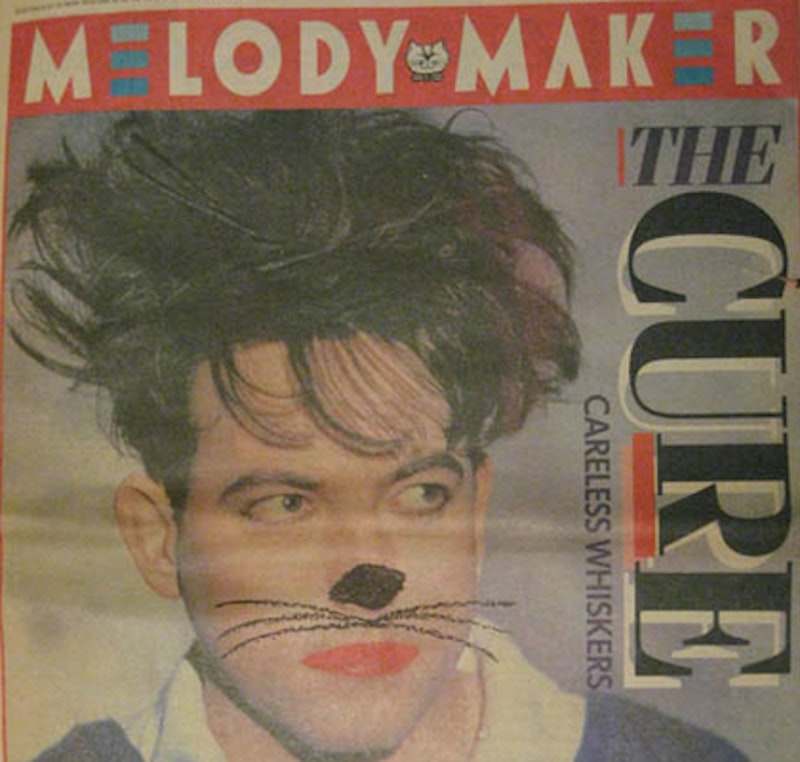

I discovered this on a recent trip to the Library of Congress. I had gone there to look up old issues of Melody Maker, the British music magazine that folded in 2000. I was in college in the mid-to-late 1980s when Melody Maker was at its creative peak. A gifted journalist named Allan Jones had been hired to helm the magazine in 1984, and he would gather some of the best writers in rock criticism or any other field—people like Chris Roberts, Steve Sutherland and Simon Reynolds. A recent conversation with a friend about the terminal state of popular music writing made me pine for the days of MM; a trip to the Madison building of the Library of Congress led me to the entire run of the magazine.

I soon realized that I didn’t need to go through the entire run of Melody Maker to prove my point that rock music writing today is clichéd, soporific, and unreadable. I only had to read one month of the weekly. I decided to start in January 1987, a date that marked the middle of my college years. I figured I could start there and move my way backwards and forwards, plucking any gems I found to create a compilation of greatest hits. I never got out of January. There was, in those 31 days, so much rich material that I used up all the money—$10—I had put on my copy card. One of the first pieces I saw was from January 3, 1987, a review, by Chris Roberts, of a live show by punk godfather Iggy Pop. Here’s its first paragraph:

It’s in the white of my eyes. The rest of the world, if there still is one, can lie down and die. Tonight Iggy is the strongest, the loudest, the dirtiest, the best, the worst, the fittest of the survivors, and the most powerful propaganda for LIFE I’ve seen on a stage since the Good Luck Theatre Company’s Sam Shepard perspective. Iggy’s been reading a lot of Sam recently, and some Edward Albee….He never stops moving.

It’s more than two decades old, yet still ignites off the page. It is passionate, literate, free of cliché, and charged with a sense of adrenaline and fun. You can tell Roberts loves the music, with a love that explodes the crustaceous tropes that have come to signify rock writing. He takes it seriously as art, and yet also feels its joy, its thrill. Roberts’ piece is more vital, readable and powerful than the reviews that appeared in my copy of today’s Washington Post.

The formula for rock writing these days is very simple, and more conservative than a Republican barbecue in Texas. First, the rock writer must convey a sense of aloofness—he’s the judge, after all, and can’t get too carried away. Second, he must seem knowledgeable, so it’s necessary to toss in some facts about the artists. But he’s also lazy, so most often these facts are cribbed from a bio sheet provided by a record company. Third, he must be liberal, awarding bands extra points if they grumble or seethe with resentment about Republicans and conservatives. Finally, he must employ the arsenal of rock clichés so expertly itemized in the small book The Rock Snob’s Dictionary.

Music is must be “atmospheric.” Something isn’t loud, it’s a “rave-up.” A guitar riff is “coruscating“ or it “jangles.“ Great albums are “seminal.” And, of course, lifeless descriptors must be used: “indie rock,” “alt-country,” “trip-hop,” “post-punk.” Breaking out of these formula, using different references or simply getting so carried away—by a music whose charm is, as U2’s Bono once put it, is that it makes you “abandon yourself to it”—is unthinkable. All while covering one of the most exciting art forms in the world.

Here are some reviews from a recent Washington Post. A new album by Amos Lee: “Last Days at the Lodge opens with a burst of Dylanesque swagger, a reminder that singer-songwriter Lee once toured with the folk-rock legend. But soon Lee moves on to what he does best: smoothly evoking his R & B and soul influences in ways that seem far more heartfelt than derivative.” Another piece calls Alejandro Escovedo an “alt-country-deity-cum-mainstream curiosity.” And here’s Paleolithic rocker Joe Cocker—“when he sings Stevie Wonder’s ‘You Haven’t Done Nothin’,” writes Post veteran Geoffrey Himes, “Cocker isn’t revisiting ‘60s radical chic; he’s channeling genuine anger about today’s politics.”

Of course. If there’s one thing that will give any modern rock musician a pass with critics, it’s liberalism. Indeed, they deduct points if a musician is not fully committed to the cause. In his review of Coldplay’s Viva La Vida, Rolling Stone’s Will Hermes deducted points because the band, whose opinions are just to the left of the Daily Kos, was not sufficiently anti-Republican. “There's something troubling about his lack of clear political messages,” Hermes notes, adding that, “the title track seems to be about the end of an empire. But its rousing chorus—‘I hear Jerusalem bells a-ringing/Roman cavalry choirs are singing’—feels like a rallying cry for a Christian empire. Where's an Arabic violin break when you need one?”

This kind of useful idiocy can reach levels of self-parody. John Cougar Mellencamp’s Life, Death Love and Freedom is, according to Rolling Stone’s Mark Kemp, something of a downer: “There’s not a bright, catchy riff or fist-pumping anthem to be found among these brooding, low-key songs about growing old, sick, lonely and pessimistic.” So why the four stars? Well, “it’s unlikely that the Republican candidate would find anything useful for his campaign on Life, Death, Love and Freedom.”

While the writers for Melody Maker were hardly RNC members—or rather Tories, as it was a British paper—they never hesitated to gore rock and roll sacred totems. In one series called “Pop! The Glory Years” they marked John Lennon’s descent into nutty self-importance, concluding that even years before his death “he just didn’t martyr anymore.” They ran lists of “The Ten Worst Band in the World,” and included Led Zeppelin—“revile them always”—and, yes, the Beatles: “Loveable mop tops, my back passage.” Editor Allan Jones, writing about Los Lobos, examined their songs as elegy for modern America—and concludes that they indeed are, but concludes that “in the end there is only prayer.” This is honest, full-bodied criticism, not beholden to any agenda but the writer’s own expansive honesty and intelligence.

In 1987 MM writer Simon Reynolds went to a show of gloomy rockers The Jesus and Mary Chain and indicted not only the band but the audience: “Of course the fans—a sad-eyed sea of black clothes, black dye, leather and hair gel—were satisfied. But then these people will be here in 1997, wanting the same things from rock, the same ritual.”

In 2007, 2008 and 2009 as well.