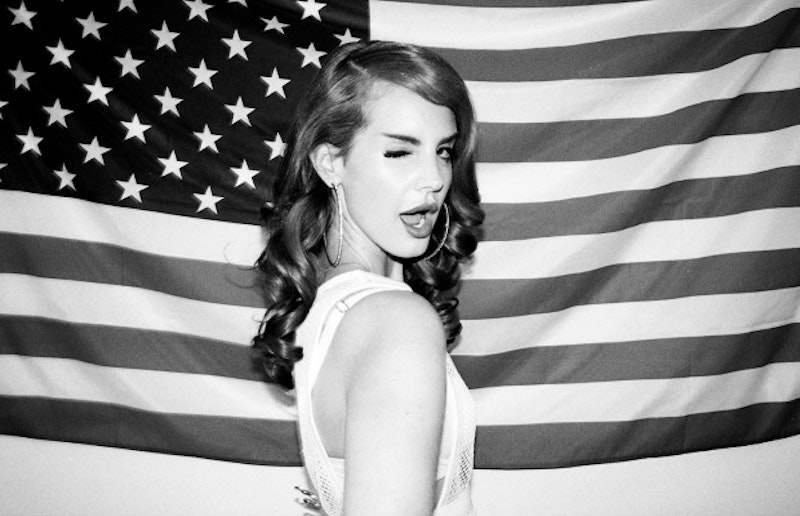

Lana Del Rey, “West Coast”

If Lana Del Rey’s management team had any sense of timing, they’d capitalize on the pasting that perennial pop punching-bag Lilly Allen is suffering over Sheezus and sneak Ultraviolence out under the cultural radar, already. No shrinking violet, Del Rey—if she weren’t made of stern stuff, the avalanche of derision that greeted her debut would’ve done her in by now. That new single “West Coast” is a seductive grower bodes well for its staying power; unlike “Cola” or “Born to Die” or “Ride,” I had to listen to it seven or eight times before I could reconstitute its melody and composition from memory. The song is unexpectedly, dreamily organic—a sort of super-stoned garage-rock creamsicle—with nary a drum machine in earshot, and suggests a pair of interlocking merry-go-rounds revolving at differing speeds: the verses huskily extoling a terrestrial Western hagiography that a hash of guitars and pedals indulge, the refrain skydiving through cloud cover, high on morphine and vocal filtering. Someday, Courtney Love will cover “West Coast” unironically, or Quentin Tarantino will use it in a movie, or both.

Kim Deal, “Are You Mine?”

Only Kim Deal could conflate lovesickness and milk-carton (or lost pet) dolor and make it sound like the Everly Brothers. There she strums, spinning apparent vulnerability into a steely diffidence in metronome waltz time. “Are You Mine?” feels, oddly, like a validation of an impression I’ve had of Deal post-Last Splash: the less adorned her songs, the more willing to embrace space and scarcity, the stronger and more potent her songwriting gifts become. That was already apparent on Pacer, the lone 1995 album from her one-woman project the Amps and the indelibly crucial “Off You,” which illuminated the Breeders’ otherwise alright Title TK. Lionel Richie famously inquired, once upon a time, “Is it me you’re looking for?” Deal at first seems to be thinking along similar lines, inferring a desire to be found or rescued, but very, very gradually it becomes clear that the title question is wholly rhetorical, the plaint of an escapee. By that point, she’s got us eating from the palm of her callused hand.

Mariah Carey, “You’re Mine”

A surfeit of good will has built up for Miguel in recent times, presumably because he has interesting hair and a winning smile, and favors fashion-victim leathers. The upstart singer joined forces with Mariah Carey for “#Beautiful,” a wet dream for poptimists and a curio for everyone else. Both camps, if they’re honest, will concede that “You’re Mine” is a superior single, in part because producer Rodney Jenkins favors the bright, flowery melodic flashbulbs that flatter Carey’s telegenic pop glow, and because the only voices accompanying Carey are, in fact, Carey’s own. Indeed, Jerkins and Carey give us husky Careys, strident Careys, grateful Careys, reflective Careys, starry-eyed Careys, a couple token soaring-melisma Careys. Wanton sexbomb Carey is missing-in-action—presumably double-parking Barbie’s dream Porsche or out on Hollywood Boulevard with a white-faced Nick Cannon—but she is hardly missed, and, as heady devotional fluff, “You’re Mine,” a sweet, silky trifle about a true love ideal that might have been torn from the diary of a high-school freshwoman, is all the stronger for that particular Carey’s absence. It doesn’t touch the canonical Carey barnburners, and is unlikely to inspire wood in anyone’s inner 14-year-old boy; no one is ever going to murder this song on American Idol.

—Raymond Cummings is the author of several books of poetry, including Crucial Sprawl, Seven New Poems, and Assembling the Lord. He blogs infrequently at Voguing to Danzig.