On December 14, 1894, Edward MacDowell strode onto the stage of Carnegie Hall. He passed through the ranks of the New York Philharmonic. He acknowledged the conductor, Anton Seidl, renowned as a passionately romantic interpreter of contemporary composers who, less than a year before, had led the Philharmonic in the first American world of a major work, Anton Dvorak’s Ninth Symphony, “From the New World.”

Then MacDowell sat down at the concert grand. Seidl raised his baton. The orchestra began playing MacDowell’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in D Minor. It had been first performed in Boston some five years before. The concerto had not previously been performed in New York.

Before the advent of the phonograph and the radio, orchestral music could be heard only in live performance. Thus, the piece was in a real sense new to New Yorkers—and MacDowell himself was a magnificent pianist at the top of his form. He triumphed, and in the hour of performance, his work seemed to stand on the verge of immortality. W. J. Henderson of The New York Times found the concerto impossible to speak of "in terms of judicial calmness, for it is made of the stuff that calls for enthusiasm…here is one young man who has placed himself on a level with the men owned by the world."

By the beginning of the 20th century, MacDowell was world-renowned as America’s greatest living composer. His concerti, sonatas, tone poems, and song cycles were performed throughout Europe, in Japan, even in South Africa. Some contemporaries—Seidl in particular—declared him superior to Brahms. Yet today, perhaps, outside Peterborough, New Hampshire, home of the artists’ community MacDowell, formerly known as the MacDowell Colony founded by his widow, Marian, he seemed until a few years ago nearly forgotten.

Edward Alexander MacDowell was born at 220 Clinton St. in Manhattan on December 18, 1860. His father was a prosperous wholesale milk dealer who loved the arts; his mother, having seen to it that he knew French, Spanish, German, Latin and Greek, arranged his first piano lessons. In 1876 he was sent to the Paris Conservatoire, then, as now, one of the world’s leading conservatories. At 16, MacDowell was the youngest applicant in a pool of 300, and his performance in the entrance examinations won him one of the two scholarships awarded that year to foreign students. Yet he found the Conservatoire’s method of teaching piano—which relied heavily on sight-reading skills—to be pointless and absurd. His instructors wanted him to play music with the score turned upside down or to transpose it into a different key, and directed him to correct the work of earlier composers, such as Bach, so as to make it conform to the Conservatoire’s notions of what constituted proper composition. MacDowell wanted to work and felt he was being taught to play games.

After hearing the Russian virtuoso Anton Rubenstein burn up the piano in a bravura performance of Tchaikovsky’s concerto in B-flat minor at the Paris Exposition of 1878, he resolved to leave Paris, where he’d never learn to play like that. Despite his youth (now 18), he won a place at the Frankfurt Conservatory, where most of his classmates were closer to 30. There he found instructors who dared to teach and play the classics "as if they had actually been written by men with blood in their veins."

One day, one of MacDowell’s teachers, Joachim Raff, a composer, interrupted MacDowell while he was supposed to be practicing. He was actually just fooling around at the keyboard. Raff asked about the piece MacDowell was working on. Embarrassed at being caught idling, MacDowell, though usually candid, said he was working on a composition. Raff asked to see it when it was done. Feeling trapped (and liking Raff, as well), MacDowell chose to deliver. He wrote his first piano concerto over the next two weeks. Raff glanced at it. Then he scribbled a letter and said, "Take it to Liszt."

Franz Liszt had created the stereotype of the great Romantic pianist and lived the rock star’s life, groupies and all. Now, in the fall of 1881, he lived in semi-retirement in Weimar. MacDowell arrived at Liszt’s home with Raff’s letter and the concerto’s manuscript. Shyness overcame him; he could not raise his hand to the doorbell, and so he sat in Liszt’s garden for an hour. Then the old man himself came outside and escorted MacDowell into the house. After MacDowell had warmed himself, he played the concerto. Liszt used his influence to have MacDowell’s works placed on concert programs. He also persuaded his own publishers to take the piano concerto.

MacDowell remained in Germany for the next decade, teaching, composing and performing. He married Marian Nevins, a young American woman among his students, in 1884. The marriage was a wonderful success: Marian later wrote, "There was an extraordinary camaraderie between us which we never lost… Until he died, he gave me what few women ever have (from a man), his absolutely undivided affection…"

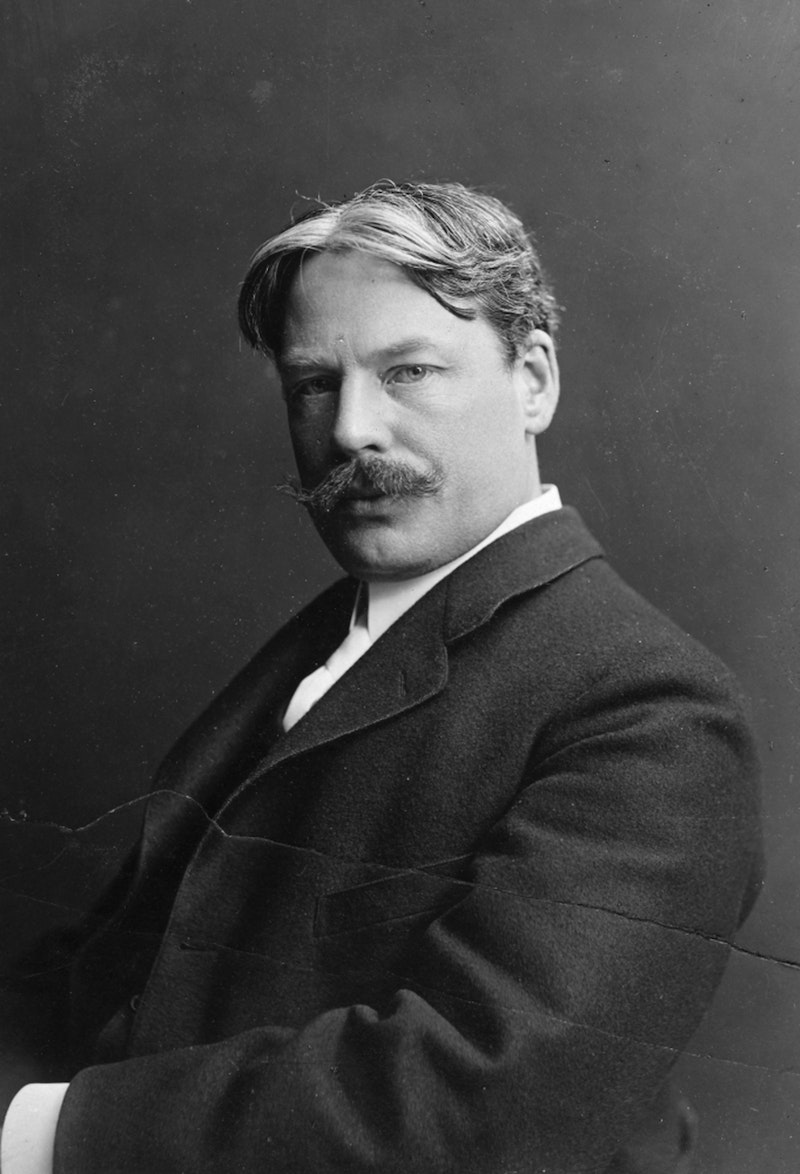

The first concerto, premiered in 1885, made MacDowell famous overnight. Stirring in mood, dazzling in technique, it provided him with a splendid vehicle for concert performances. So did his fiendishly difficult Witches’ Dance, a bit of showmanship that knocked their socks off across Europe. Critics hailed MacDowell’s mastery of the keyboard, his supreme power and control, as well as his striking stage presence. Tall, slender and broad-shouldered, with muscular arms and hands, he had jet-black hair and flashing blue eyes. All this, along with a flamboyantly waxed dark red mustache, must’ve made him irresistible.

In 1888, the MacDowells came home. They settled in Boston, then the center of American musical life. There MacDowell taught and went on national concert tours. His piano miniatures Woodland Sketches and New England Idylls, his settings of To a Wild Rose and To a Water Lily were on drawing room pianos throughout the country even as his larger works were performed from Portland to San Francisco. During his Boston years, he wrote four massive piano sonatas, the Tragica, Eroica, Norse, and Keltic, each investing (or warping, as MacDowell self-deprecatingly said) the sonata form with symphonic grandeur.

On January 23, 1896, MacDowell gave a return performance of his Second Concerto with the Boston Symphony at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House. Seth Low, president of Columbia University, was in the audience. Earlier that year, Columbia had received a grant to establish its first professorship of music. In April 1896, Low offered MacDowell the job. He was 35.

MacDowell was Columbia’s music department. He taught seven courses, each a year long and meeting two to three hours weekly. He did all this without teaching assistant or secretary. He had to deal with everything from purchasing desks, pianos, and library books to hiring outside lecturers, ordering chalk, and keeping the instruments in tune. He often re-tuned the pianos himself—it was easier than fighting with the University’s business managers, who could not understand that over time pianos do go out of tune. MacDowell slaved over the organization and content of his lectures to have them appear spontaneous, and also provided substantial individual instruction and individual examinations.

In 1901, Seth Low was elected mayor of New York and resigned from Columbia’s presidency. His successor, Nicholas Murray Butler, was a very different kind of man—an arrogant power seeker, far more interested in administration and in the idea of the educator than in ideas themselves. A mere five years in the classroom teaching philosophy had convinced Butler that education was a science. He had founded Teachers College, successfully lobbied for compulsory state licensing of teachers (all of whom were required to have a degree in education, thus promoting the interests of the education industry), and advocated the centralization of the New York City schools, all reflecting Butler’s faith that centralized authority in the hands of men such as himself inevitably led to improvement.

Unfortunately, MacDowell chose this moment to propose restructuring Columbia’s curriculum, passionately arguing that some education in at least one of the fine arts was as essential as in science or history. Butler opposed the idea, largely because the mainstream faculty felt threatened by it, and it seemed politic to soothe their feelings. But MacDowell persisted. Butler saw this as a challenge to his authority. At first, he began spreading sly, personal speculations about MacDowell’s character, temperament, and intelligence among colleagues—all behind the composer’s back. He stripped the arts faculty of voting rights on academic matters. Finally, he openly denounced MacDowell for unprofessional conduct and “sloppy teaching.” MacDowell’s proposal was rejected in September 1903. He resigned the following February.

In March 1905, MacDowell was knocked down by a hansom cab at Broadway and 21st St. in New York. One wheel rolled over his spine. The injuries were physically and emotionally debilitating. They darkened the depression he’d endured since his resignation. Over the summer, his hair turned white. By November, his gait had become unsteady. His physicians never quite diagnosed his illness: Alan H. Levy, in Edward MacDowell: An American Master, speculates that his depression and injuries led to a progressive aphasia. By the winter of 1905-06, he was dying. Friends raised funds to defray his medical expenses. Seth Low privately gave $2000 to Marian MacDowell and lent the MacDowells his car. Butler didn’t even send a get-well card.

Now he was attended by a full-time nurse and a servant who carried him about. By the summer of 1907, he no longer recognized his parents. On January 23, 1908, his wife said to him, "Won’t you give me a kiss?" He managed to pucker his lips. He looked at her for the first time in days with something like recognition. Then he stopped breathing. He was 46.

His reputation was as the wild rose that fades. By the 1930s, Aaron Copland and Virgil Thomson, who should’ve known better, dismissed MacDowell and his contemporaries as genteel, over-gentlemanly and bourgeois. Copland claimed none of them wrote with fire in the eye: "There were no Dostoyevskys, no Rimbauds among them; no one expired in the gutter like Edgar Allan Poe."

Levy, in his Edward MacDowell, has called this transformation of American musical culture "the great erasure." He suggests that the Copland generation wanted to believe themselves the first American composers in whom the nation could take pride. They weren’t, of course. The eclipse of MacDowell and the American composers of his generation occurred during the Depression-era seizure of the nation’s musical establishment, particularly musical criticism and orchestra programming, by advocates of post-tonal music, marked by dissonance and atonality. They sent much of America’s existing musical culture down the memory hole until its rediscovery within the last generation.

In later life, Copland was eight times a resident Fellow of MacDowell. While at MacDowell in 1944, he composed Appalachian Spring, which won a Pulitzer Prize in 1945. In 1962, he became the second recipient of its Edward MacDowell Medal, annually awarded to one person who has made an outstanding contribution to American culture and the arts.

Virgil Thomson, who had been three times a resident Fellow and received the Edward MacDowell Medal in 1977, finally admitted, shortly before his death in 1989, that MacDowell’s reputation might supplant that of MacDowell’s contemporary Charles Ives. Ives’ cantankerous personality and freakish originality had long charmed the critics. Only in our time have some critics begun quietly admitting that much of Ives’ work is unlistenable.

Nicholas Murray Butler remained president of Columbia until 1945. During the Great War, he purged the faculty of antiwar professors and did the same to leftists during the 1930s and 40s. The Republicans nominated him for vice president in 1912. He unsuccessfully sought their presidential nomination in 1920. His support for the Kellogg-Briand pact of 1928, one of many attempts between the World Wars to preserve peace without creating means to enforce it, won him the Nobel Peace Prize in 1931.

He is now almost forgotten. The reputation of Edward MacDowell continues its steady re-emergence from obscurity.