Full disclosure: I got to know Travis Miller (aka Lil Ugly Mane) about as well as one might expect to know an artist whose most famous record is titled Mista Thug Isolation, which is to say barely at all. This was 10 years ago. He moved into a Baltimore row home I lived in for a few months, an animal house with five other men including myself. He was a personable guy, but his masterpiece rap album seems aptly-titled in retrospect: except to smoke a cigarette or bake a batch of cookies, he seldom left his room, usually opting to work on music while the rest of the housemates were partying. I mention this not as a weaselly namedrop, but because 10 years and about as many records after living with the guy, Miller’s still a mystery to me, and that feels intentionally cultivated, the deliberate remove at the heart of his projects.

Lil Ugly Mane’s rise in popularity in the early- to mid-10’s saw a backlash among purist rap heads, who dismissed him as derivative of 1990s Memphis rap and horrorcore acts. Beside the fact that Ugly Mane never really adopted the triplet flow popularized by Lord Infamous and Bone Thugs, or that his beats (all self-produced, usually under the pseudonym Shawn Kemp) were just as rooted in golden-era East Coast rap as they were Southern rap, this argument ignores how vivid his lyrics can be, especially in his post-Mista Thug Isolation work where he traded in his earlier drug dealer/cryptkeeper persona for something more earnest and heartfelt.

Miller made a few more rap records as Lil Ugly Mane, including the excellent Oblivion Access, before releasing the uncomfortably confessional volume 1: flick your tongue against your teeth and describe the present under the name bedwetter, a full-blown emo rap EP that recalled Bushwick Bill’s heavier songs more than anything from Memphis. After that, except for the short-lived group Secret Circle and a few small side projects (a compilation of experimental projects called register, a jazz album under the name Dale Krugler), Miller’s output mostly ceased. Fans and critics were left to wonder: did one of underground rap’s most removed voices remove himself from the game?

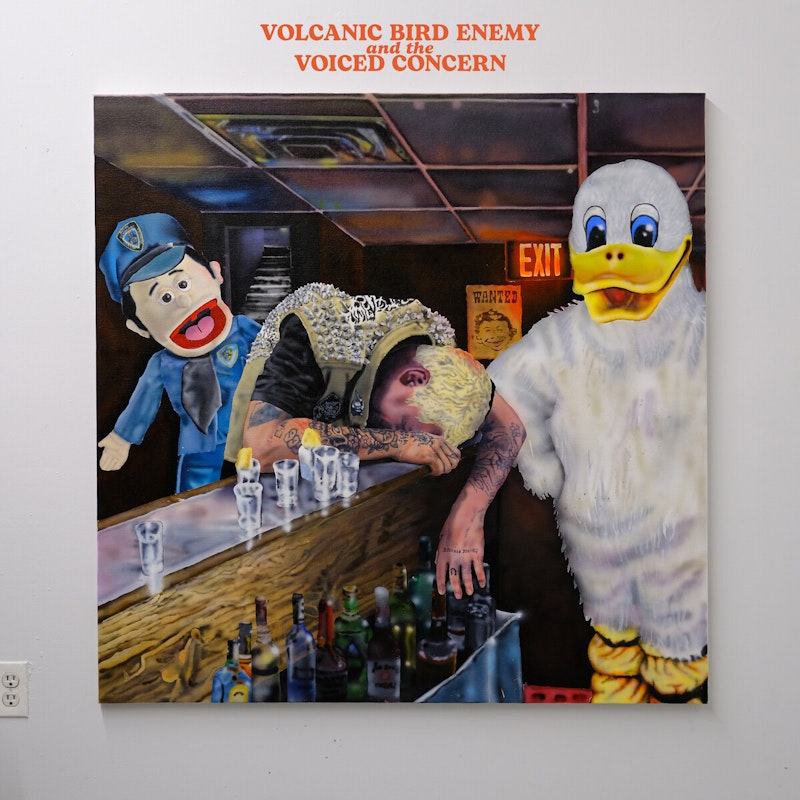

Yes and no. This year Lil Ugly Mane released music again, but it wasn’t what anyone expected. It wasn’t rap. The first singles, “Headboard” and “Porcelain Slightly,” take a more understated approach to vocal modulation than previous Ugly Mane records; gone are the pitch-shifted blaccents of his early raps, swapped for soft crooning filtered through hazy reverb. These songs were a welcome return but also easy to dismiss as the latest experiments from an artist who once started a blog in which he made a song from a different genre every day, which is why it came as a surprise when he released a full album of non-rap music, a 19-track opus chocolate-starfishily titled Volcanic Bird Enemy and the Voiced Concern.

Like most Lil Ugly Mane albums, it opens with an instrumental; here he ditches the noise intros of Mista Thug Isolation and Oblivion Access for something that sounds closer to a track off his Three Sided Tape: dreamy synths cruising along a plane of overlaid samples—sax, violin, piano—while a looped Siri voice repeats: “Who are you?” Is the record that follows Miller’s attempt to answer this question? Is he asking it of the listener? A former lover? There’s evidence to suggest all three, and his answers are more of the quotable self-negating misery and scorched-earth misanthropy of his post-Isolation work.

“With Iron & Bleach & Accidents'' opens with a music box reminiscent of Buddy Holly’s “Everyday,” juxtaposed against the acerbic first lines: “Every time I hear you moaning, every time you feel deprived/people under dynamited buildings take a break from smoldering and smile.” This sets the tone, not just lyrically but also its production: sad songs that cull liberally from jubilant sources (ragtime on “Styrofoam,'' breakbeats on “Into a Life,” new wave on “Broken Ladder”), filled with bitterness and schadenfreude. “Cursor” finds Miller singing over a looped trumpet and slow surf guitar about his ambivalence towards his partner (“I don’t like when you’re unhappy/But I don’t like it either when you’re great”), before closing out in a Zen state of resentment: “I hope it’s worse for you today, I hope it’s bad for you.” At first this repeated refrain sounds like an inverted version of Arthur Russell’s “You Can Make Me Feel Bad,” a soft and beautiful song undercut by the emotional S&M of its lyrics, but then the bouncy synths and “Mmmbop” drums kick in and suddenly it sounds like it could be closing out an episode of Malcolm in the Middle. It’s a trip.

The kind of repetition that pays off in the coda of “Cursor” is less successful on tracks like “Stock Car” and “Human Fly,” which are rushed sketches; when Miller relies too heavily on repeated choruses and refrains, the songs lack the kind of lyrical precision that defines his best music. Those tracks are the exceptions though, and the rest of the record finds Miller sharper and more energized than he’s been in years, especially on the subject of the unnamed lover (the unrequited love song “Clapping Seal,” the alone in a four-cornered room depression hymn “VPN”).

While a lot of these songs read as personal relationship post-mortems, it’s possible that the you on this record—the second person is utilized in several songs—is fluid and non-specific, which points to one of the rewards of continued engagement with Lil Ugly Mane’s music: a shared feeling of disgust with the outside world, and the people who inhabit it. “Meet me in the countryside, where the mountains look like hostages tonight,” he sings on “Hostage Master,” reflecting on a Mother Nature taken ransom by humankind and concluding, “I don’t think we have the right to be alive.”

It wouldn’t be a Lil Ugly Mane record if some of that disgust wasn’t internalized, as he does to parodic levels in the chorus of “Discard” (“I’m the enemy of progress, I just want to be discarded”). This chorus feels like a self-conscious jab at his own histrionics, given the relatively low stakes of the preceding lines (“Have a tendency to promise shit that I cannot accomplish/Like the energy to take the garbage out of my apartment”), the post-Nirvana mallternative guitars and the record scratching, a winking ode to Millennial ennui and defeatism mirrored against the same plasticized sentiments of the preceding generation.

Which isn’t to say that Miller is simply an ironist or that his disgust isn’t genuine. Volcanic Bird Enemy is probably his most genuine album, or at least his most relatable. This isn’t because Miller’s less removed or distanced or mysterious; it’s because in 2021 most are more isolated, stuck behind our VPNs—finally on Lil Ugly Mane’s miserable wavelength.