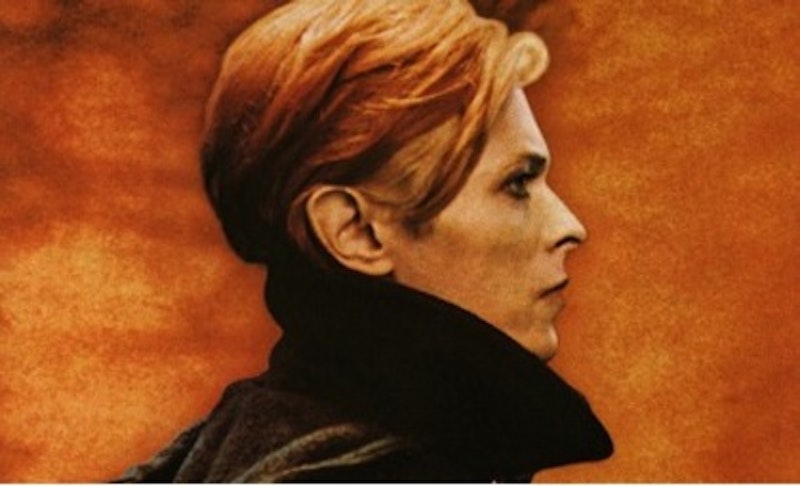

There comes a time in a great artist’s career where he or she takes a brave artistic turn. A popular (and somewhat clichéd but accurate) example can be Bob Dylan going electric in ’65. Another example could be Miles Davis fading out the quintet sound in the late 60s and forming a 20-member jazz-fusion ensemble. Other examples spring to mind: Tom Waits adding the bagpipes and marimbas in the 80s, Talking Heads dropping the post-punk for an Afro-Beat sound, or simply The Beatles releasing Sgt. Pepper’s. But the high prince of the musical about-face is David Bowie. His abrupt style change in the mid-70s angered people in the beginning, but has gained a following over the past 30 years. At the time, it was hardly possible to compare Bowie’s early music to his so-called “Berlin Trilogy,” but any true Bowie fan will tell you that this period was Bowie’s most creative and influential. And now the complete story of Bowie’s German period is finally recorded in the book, Bowie In Berlin: A New Career In A New Town.

Written by Thomas Jerome Seabrook, this is the book that all obsessive late 70s Bowie listeners have been waiting for. The book’s title respectively refers to Bowie’s stay in West Berlin from 1976-1979. During this time, Bowie wrote and released Low in January 1977, “Heroes” in October 1977, and Lodger in May 1979, with the live album, Stage, appearing in 1978. Incidentally, only the trilogy’s second album, “Heroes” was fully recorded in Berlin, while other recordings took place in France, Switzerland and New York.

The book is an accurate 254-page account of Bowie’s life in Berlin. Seabrook writes as if the story was a piece of fiction. He introduces the protagonist, Bowie: a young international British glam pop star who writes one hit after another as if it were a routine. Like his contemporaries Marc Bolan of T. Rex and Elton John, Bowie was a big name in the early-mid 70s glam rock scene. With the releases of The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars in 1972, Aladdin Sane in 1973, and 1974’s Diamond Dogs, (plus a 1973 cover album, Pin-Ups), Bowie had fully seen worldwide fame. But like what Seabrook describes, with great fame comes terrible suffering. By 1975, with the release of the hit album Young Americans, Bowie’s cocaine addiction was so dire that he looked like a living ghost. Frustrated with his fame, Bowie’s stage alter ego of Ziggy Stardust was so large that more people knew Ziggy than Bowie. While Elton John could go to sleep at the end of the day as his original self, Reginald Dwight, Bowie had to play the Ziggy act night and day: “That fucker would not leave me alone for years,” Seabrook quotes, “That was when it all started to sour… And it took me an awful time to level out. My whole personality was affected.”

And that “awful time to level out” is only a lighter term to describe what exactly he went through. His constant drug abuse was a simple way to escape his Stardust aura, and it seemed to affect everything he did. People even blame his addiction on the terrible original mix of the Iggy and the Stooges’ 1973 album Raw Power, which he produced during the early stages of his cocaine trend. 1976 saw the release of Station To Station, which was a more clear departure of his glam pop sound than its’ predecessor Young Americans. 1976 was also a big year for Bowie, as the lead actor is Nicholas Roeg’s The Man Who Fell To Earth. So with the astronomically tiresome fame of music and theater, Bowie was desperate for escape.

Living in Germany was a completely different than his lifestyle in L.A. Just over 30 years after the end of World War II, Berlin still hadn’t caught up with the times. Living in the war-ridden city, Bowie gained great inspiration from the isolation and staleness for his new album. Also, by living in Germany, Bowie was exposed to German rock, or what the music press began to call “Krautrock,” consisting of stellar bands such as Kraftwerk, Can, Neu!, Faust, Amon Düül II. Krautrock is deservedly described as post-psychedelic instrumental free-form jamming. With new surroundings offering new sounds, it was a given that Bowie’s new material would definitely sound “new.”

The body of Seabrook’s account is the origins of the Berlin trilogy, and what it was like working with new collaborators like Iggy Pop, Adrian Belew from King Crimson and Talking Heads, and the most important collaborator of the time, Brian Eno. Almost like Bowie’s long lost twin brother, Eno started off in the glam scene in the early 70s with his collaboration with Roxy Music, and then going solo with his 1973 debut record Here Come the Warm Jets and then Taking Tiger Mountain (By Strategy) a year later. His third album, the beautiful Another Green World, released in 1975, was a critically acclaimed change. Instead of an album of the usual radio-friendly pop songs, Another Green World featured heavily synthesizer-dependent songs, the majority being instrumental. While his prior works would sound best on the radio, Another Green World had a more museum feel to it. (Any person who can listen to the track “Becalmed” and not feel beside his or herself simply has no heart.)

Eno was no stranger to ambient and bittersweet music. His collaborations with Robert Fripp for the albums No Pussyfooting in 1973 and Evening Star in 1975 proved his ability to make ethereal compositions. By 1977, he was a common name in the art rock/ambient music scene, with albums such as Discreet Music and Before and After Science, and his collaborations with krautrock pioneers Cluster for the fittingly titled 1977 album Cluster and Eno, Eno had made his trademark music. In 1976, Eno and Bowie finally decided to record together after several years of friendship.

The first side of Low starts with a fade in and kicks right into the instrumentally upbeat “Speed of Life,” followed by five vocal pop songs echoing the sounds of punk, new wave, disco and even 70s radio balladry; a sound that was a post-Another Green World yet pre-Gary Numan approach. The last song of Low’s first half, “A New Career In A New Town” follows the similar tempo and instrumental nature of the first track, but done so in a more melancholy and atmospheric fashion, and then fades out. Seabrook makes an excellent observation that although it may be Bowie’s strongest installation of the Berlin Trilogy, most of Low’s songs seem incomplete due to their abrupt fades in the end, giving the album a dry continuity. This odd pacing could’ve reflected Bowie’s actual frustration and boredom of his drug-ridden life.

Seabrook writes in a very encyclopedic fashion. The book has several shorter sections that include track-by-track dissections of the trilogy’s first two records, and then Iggy’s two Bowie-produced albums, the The Idiot and Lust For Life, both released in 1977. The midnight-movie induced necrophilic sound of Pop’s debut earned him and Bowie critical acclaim upon it’s March 1977 release, and the heroin-ridden Trainspotting-favorite Lust for Life only made Bowie and Iggy’s reputation even stronger.

The absence of Lodger’s analysis is no accident. Seabrook claims that the album was the weakest installment of the trilogy, stating that it was when Bowie and Eno were at their creative wits’ end with themselves and each other. The album itself doesn’t have a concrete theme like its predecessors. The overall feel of the album is weak, empty, and downright incomplete.

As the 70s came to an end, so did Bowie’s collaboration with Eno. Like a hero continuing to conquer after his finest moments, Bowie continued to win the ears of millions, with early 80s hits of “Let’s Dance,” “China Girl” and the Freddy Mercury collaboration “Under Pressure,” not to mention the severely underrated album Scary Monsters right after Lodger. Nobody can really hate the classic 80s radio hits, or watching Bowie’s acted wizardry in Labyrinth, but his post-Berlin works just don’t have the same artistic mojo of those three albums. The Berlin Trilogy has gained a quiet legacy. Nine Inch Nails’ Trent Reznor stated that the main influence of NIN’s top album The Downward Spiral was Low, while other bands such as Of Montreal cover Berlin-era classics.

It’s a shock that Bowie’s work hasn’t gained more coverage. For years we’ve seen a plethora of novels, documentaries and other works based on The Beatles, The Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, even Nirvana (?) and Sublime (!). Personally, Bowie’s Low, “Heroes” and Lodger are where it all began for me. Ever since hearing “Heroes” blast from my older brother’s room one muggy summer afternoon, and then finding a copy of Low for $10 at a vinyl shop a few years later, and listening to these albums endlessly, the impact this music has left on me is profound. Call it a cliché, call it a stereotype, but people sometimes find things that they just “get,” and for me, it was Bowie.

Making this music, Bowie taught us one thing: Don’t take shit from anyone if you know it’s going to work. Bowie’s record label RCA insisted he change Low for a better commercial reception, but Bowie refused because he was so satisfied with his finished work. This iconoclastic legacy lives on as much as his musical one, like Radiohead releasing their album for any price the consumer chose. The core of Bowie’s message through these albums was simply to do what your gut says: no questions, no bullshit.

Making it Neu

A new book finally sheds some light on the most creatively fertile part of David Bowie’s career.