Birmingham is England’s second city. Comparable in size to Glasgow, it’s known as Brum, or Brummagem, by people in the UK. Its inhabitants, in turn, are known as Brummies.

It’s a big, old working-class city in the West Midlands, in the heart of England’s industrial belt. In the 19th century it was known as “the workshop of the world” and “the city of a thousand trades.” Unlike other manufacturing centres it was never associated with any particular product; rather it was home to a variety of industries, often housed in small workshops scattered all over the city. Brummies can turn their hand to anything. There’s a jewellery quarter and a gun quarter. The steam engine was developed here. Birmingham made motorbikes and cars, toys, swords, textiles, leather goods, pottery, coins, locks and chocolate; almost anything you can imagine.

The name “Brum” is not a diminutive. It was probably part of its original title, as the presence of nearby West Bromwich, Castle Bromwich and Bromsgrove clearly testify.

In the 1960s, after the worldwide success of the Beatles from Liverpool, the music industry began scouring other British cities for their indigenous groups. Manchester produced the Hollies, Newcastle the Animals, Dartford the Rolling Stones, and London the Who, the Kinks and the Small Faces. Birmingham, too, had a lively and interesting music scene. Just as music from Liverpool was known as Mersey Beat, after the famous river than runs through the city, so Brummie music came to be known as Brum Beat.

The first group of any note to come out of Birmingham was the Moody Blues, who had an international hit with their first single Go Now in 1964. There were earlier British hits by the likes of the Applejacks and the Rockin’ Berries, but the “Moodies,” as they were affectionately known, were the first Brummie band to achieve fame outside the British Isles. The story goes that they developed their name as an attempt to get sponsorship from the local brewery, Mitchells & Butlers, known as M&B. They were called the MBs or the MB Five, but when the sponsorship failed to materialize, they opted to keep the initial letters of the name, adding “Moody” as a reference to “Mood Indigo” by Duke Ellington, and Blues because they were principally a blues group at the time.

They began to look like a one-hit-wonder. It was three years before the Moody Blues had another record in the charts. By this time the lead singer, Denny Laine had left, replaced by Justin Hayward, and they unveiled a radical new sound. Nights in White Satin is inspired by classical themes, centering around the judicious use of the Mellotron and the flute. Even this betrays its Brummie source. The Mellotron, as an instrument, had been invented in Birmingham, and the Moody Blues’ keyboardist, Mike Pindar, had once been a tester for the company that made the instrument.

It was the beginning of what came to be known as progressive rock. The Moody Blues have since gone on to forge an international reputation as one of the originators of this ponderous, high-minded, classically influenced musical form.

The next serious group to emerge from the Brummie scene was the Move who had a string of hits in the 1960s and early-70s, starting with Night of Fear in 1966, and ending with California Man in 1972. Although the Move never broke in the United States, the follow up band, the Electric Light Orchestra, became internationally renowned, and its leader and co-founder, Jeff Lynne, went on to greater things, including working with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty and Roy Orbison in the Travelling Wilburys.

There’s a theme here. Night of Fear was based upon the 1812 Overture by Tchaikovsky, and the Electric Light Orchestra was an attempt to graft classical instruments on to rock music, as was the Moody Blues’ concept album, Days of Future Passed, from which “Nights in White Satin” was taken. It’s as if Brummie musicians were trying too hard to be taken seriously, as if just playing rock music wasn’t enough.

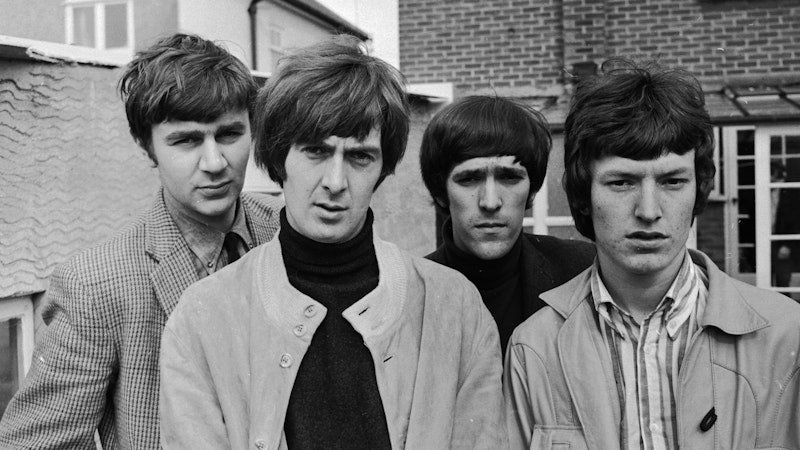

Another great Brummie band of the 1960s was the Spencer Davis Group, featuring Steve Winwood. The Spencer Davis Group was cooler and more hard-edged than its rivals, playing funky, bass-led rhythm and blues, and Winwood was a phenomenon, with a perfect soul voice, even at the age of 14, which was how old he was when he first took to the stage. He was also handy on the Hammond Organ. The group went on to score a number of hits, including Somebody Help Me, Keep On Running and Gimme Some Lovin’. After the band’s demise, Winwood formed Traffic with another group of fellow Brummie musicians, and later joined Blind Faith, with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker. Winwood, too, has become an international figure, both as a solo artist, and as a session musician of renown.

But the band which perhaps most typifies the Birmingham music scene is Black Sabbath. If you want to hear a full-on Brummie accent, just listen to Ozzy Osbourne. While other Brummie musicians have hidden their origins, putting on vague, transatlantic accents, Ozzy has never turned his back on where he comes from. He’s a Brummie through and through. Same goes with the other members of the band. All of them retained their accents.

Black Sabbath was virtually the resident band of Mothers Club in Erdington for a while. Interestingly, the Moody Blues had also been resident there, some years earlier, when it was known as the Carlton Ballroom. It was one of the principal venues for the rock scene in the late-1960s and early-70s and parts of Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma were recorded there.

The significance of Black Sabbath is that, unlike bands from other parts of the United Kingdom, they created a whole new musical genre, in the form of heavy metal. Black Sabbath’s music is characterized by epic riffs with a sinister edge, steely and loud, with doom-laden lyrics. Their lead guitarist, and principal songwriter, Tony Iommi, had lost the tips of two of his fingers in an industrial accident some years earlier, and he was forced to invent a new way of playing the guitar to compensate. He replaced his missing fingertips with home-made thimbles and detuned his guitar to make it easier for him to bend the strings. The result was that dark, heavy sound that characterises Black Sabbath’s music. At the same time, being working class, and coming from an old industrial city, the band wasn’t impressed with the flower-power lyrics of much of the music of the time, and opted instead to focus on words that reflected their more pessimistic outlook, stealing ideas from horror films and Dennis Wheatley novels. The sound of heavy metal comes from the workshops and steel mills that surrounded them when they were growing up. It was in a sheet metal factory that Iommi had lost his fingers. This was a much more urban sound, born from the inner-city landscape that was their home and, while early Black Sabbath music was derided by critics, its ongoing popularity with fans has secured their legacy as one of the most influential bands of the 20th century.

Other Brum Beat bands that attained mythical status are Slade, from nearby Wolverhampton, and UB40, from Sparkbrook. Robert Plant and John Bonham of Led Zeppelin are also from Birmingham and were both prominent in a Brum Beat band from 1967 called the Band of Joy.

The word “Brummagem” has come to mean something cheap and shoddy, an inferior copy of a superior product. That’s the way it is used in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Beautiful and the Damned. A “Brummagem screwdriver” is a hammer, reflecting the sense that Brummies are crude and unskilled at their work. In fact, the opposite is the case. Just as it was Brummie workers who built the steam engine, the BSA motorbike and the Mellotron, so it was Brummie musicians who helped create heavy metal and progressive rock.