Julien Temple has made two documentaries about the Kinks. The first, Imaginary Man, features the older of the Davies brothers, the principal songwriter of the group, Ray. The second, Kinkdom Come, focuses on Dave: less well-known, less feted, but crucial to the band’s success. It was Dave Davies who was responsible for the guitar sound on their first hit single, You Really Got Me. He did it by slicing the cone of his speaker with a razor blade, thus achieving the grungy sound that later became a staple of rock music through the use of the fuzz box. Jimi Hendrix said that it was a landmark guitar sound.

At the end of the film Temple tells Dave that his brother once said that, if he had to do it all over again, he’d change every single thing. Dave looks amused. “That’s so amazingly funny,” he says, “because I wouldn’t change any of it.”

And therein lies the difference between the two brothers. Ray is shy, awkward, inward-looking, secretive: a loner; while Dave is an extrovert: outward-looking, easy going and friendly. Nevertheless, it’s clear who’s the dominant partner in the relationship. It was Ray Davies’ genius that made the Kinks, and both brothers know it.

They started off, as was the fashion at the time, as a blues group, and the first five singles are all R’n’B numbers. The riff for “You Really Got Me”, their third single, is essentially a take on Muddy Waters’ Mannish Boy, except that it shifts up the scale, giving it a more urgent feel than the original. This goes along with the lyrics which are a fevered invocation of sexual longing:

Girl, you really got me goin'

You got me so I don't know what I'm doin'

Yeah, you really got me now

You got me so I can't sleep at night

The song was number one in the UK and number seven in the United States and catapulted them to international stardom. It was the time of the British invasion, when UK acts were storming the American charts. The Rolling Stones, the Zombies, the Hollies, the Animals, the Who, a whole fleet of bands were flying the flag for Britain over the Atlantic, riding on the wave first started by the Beatles. The Kinks were no exception. They toured the United States in 1965 and soon acquired the reputation as an unruly bunch: hard-drinking, argumentative and a handful. The tour was chaotic, involving on-stage fights and arguments with promoters and TV executives. One such incident occurred backstage just before their appearance on Dick Clark's TV show Where the Action Is on August 2nd 1965.

As Ray Davies recounts in his autobiography: “Some guy who said he worked for the TV company walked up and accused us of being late. Then he started making anti-British comments. Things like ‘Just because the Beatles did it, every mop-topped, spotty-faced limey juvenile thinks he can come over here and make a career for himself. You’re just a bunch of Commie wimps.’”

Punches were thrown and Davies got one in the face. The TV exec (or whoever it was) told them they’d never work in the US again. “You’re gonna find out just how powerful America is, you limey bastard!” he said. The result was that the Kinks found themselves banned from touring in the United States for the next four years by the American Federation of Musicians. It was 1969 before they traveled to America again, by which time the British invasion was over, and the Kinks were an almost forgotten band.

But the ban kicked off a new phase in Davies’ songwriting. There’s a new tone to the words after this, which take on a satirical edge, while the music is reflective, gentler and more lyrical. Gone is the rough-hewn R’n’B sound, replaced with folksy guitar and an emphasis on clarity of expression.

There’s also a new-found concern with Englishness and English values. A Well Respected Man is a satirical take on the English middle class. It’s observational and character-led, very class-conscious, reflecting the brothers’ poor, North London, working-class background. The fourth verse is sardonic, delivered in a posh, upper class accent by Davies, aping his betters in a way that every working-class English person would recognize:

And he plays at stocks and shares,

And he goes to the regatta,

And he adores the girl next door,

'Cause he's dying to get at her,

But his mother knows the best about

The matrimonial stakes.

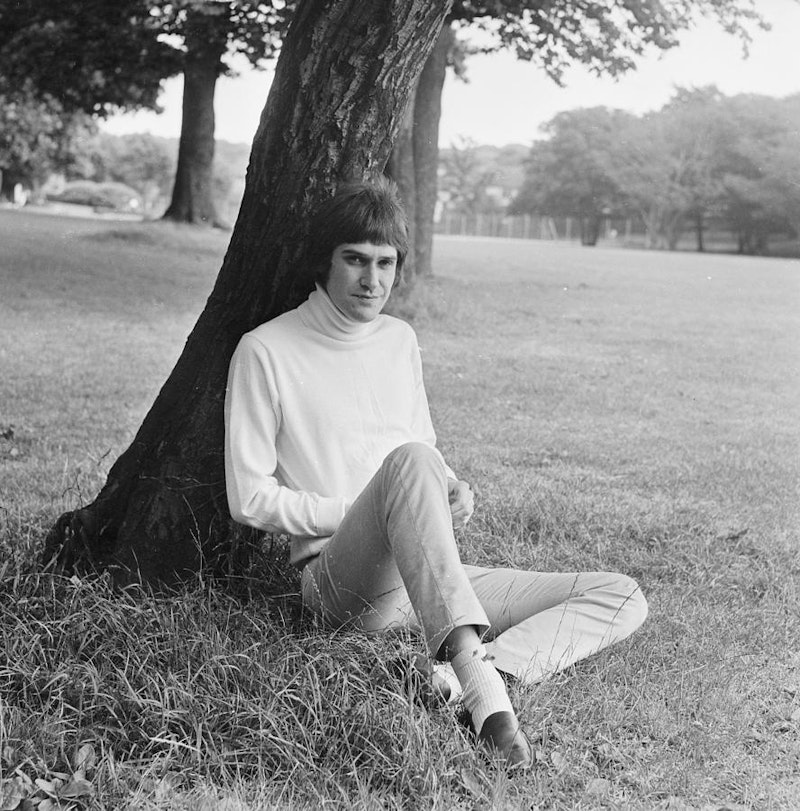

Dedicated Follower of Fashion is another satire, with a strong Vaudevillian feel; probably directed at brother Dave, who was a bit of a dandy, wearing thigh-length leather boots, and having his long hair back-combed and permed by a women’s hairdresser. This was also the first time that specific English locations are mentioned in a Ray Davies song. There are references to Regent Street and Leicester Square, the boutiques of London town and “the Carnabetian army,” reflecting the fame of Carnaby Street as a center of fashion at the time.

It’s this ability to suddenly shift the direction of his music that marks Davies from the other songwriters of his era. Long before the Beatles had met Bob Dylan and gone all psychedelic, long before the social commentary of the Who or the Bulgakov-inspired imagery of the Rolling Stones, Davies was already charting his own, unique course, while extending the parameters of what the popular song can do. There can be whimsy in a Davies song. There can anger. There can be satire. There can be deep nostalgia for a dying age, and a call to arms for the values of his parent’s generation. There can be politics and humor and irony and observation, all sung with that characteristically understated voice of his: so fragile, so constrained, so unashamedly English. There’s no other voice like it.

But it’s the song that came out on May 5th 1967 that marks him out as a genius. Waterloo Sunset stands alone. From the descending bass line at the beginning to the rising chorus throughout, from the delayed echo sound on the guitar (again a Dave Davies contribution) to the angelic harmony in the background, it’s a master class in how to make the perfect record. Ray Davies says that the tune came to him in a dream, and that it was so personal to him that he didn’t want to release it commercially. It was meant for himself and his family he said, no one else.

The words are simple but multi-layered. We have the observer at the window, meditative and calm, looking out over the Thames as it flows on into the night. We have the crowds down below, with the taxis moving about in front of the station, their headlights already glaring. We have the chill of the evening and Terry and Julie, two people differentiated from the crowds, who are obviously in love. It’s an assignation. They walk across Waterloo bridge, presumably hand-in-hand, where they feel safe and sound. We’re never told where they’re going.

Then we have the sunset, that vision of paradise. There’s something magical in this. It’s not any old sunset in any other part of the world: it’s a Waterloo Sunset, in the heart of the bustling, noisy, metropolis of London. The specificity of the location makes the message more complete. The song creates a picture in your head. Even if you’ve never been to Waterloo, nor visited the station, you know what a sunset looks like. The image of the sunset carries you to that very place, that very moment, where “Terry meets Julie, Waterloo station, every Friday night.”

There was a rumor that the names in the song referred to Terence Stamp and Julie Christie, at the time engaged in a very public affair, but Davies has denied that. It referred to one of his sisters, who was about to get married and to emigrate, he said. It was a wish-you-well for their journey to a new land. In another interview he said that Terry was his nephew, Terry Davies.

But it doesn’t really matter who it’s meant to be. It’s a universal tale, simply told. There’s no pumped-up rhetoric in this song, no overblown imagery, no grand metaphor. It’s quiet. It’s ordinary. There are people like Terry and Julie throughout the world, young people who meet in public places and who are in love. There are bustling stations and taxis and crowds in every city, in every country around the globe. And there are sunsets too, moments when we can shrug off our cares and commitments, our fears and frustrations, and be at one with the beauty of the world.

This wasn’t the last song that Davies wrote. There’s a string of hits stretching into the early 80s, and at least one widely recognized cult classic album, in the form of The Kinks Are the Village Green Preservation Society. The band were still touring and recording until 1996, and Davies has had a successful solo career since then. But it is Waterloo Sunset that defines him. If he’d never written another song, his reputation as one of the greatest English songwriters of all time would remain intact.