From the 1950s to the Vietnam era, artist Reid Miles invented and perfected the distinct visual style of Blue Note Records. Miles’ assemblage of experimental typography, dynamic layouts, abstract clip art, and moody photography was a highpoint in graphic design’s history. One element of Blue Note cover art that’s rarely discussed is its subversion of sexually-charged commercial strategies and narratives related to traditional feminine iconography.

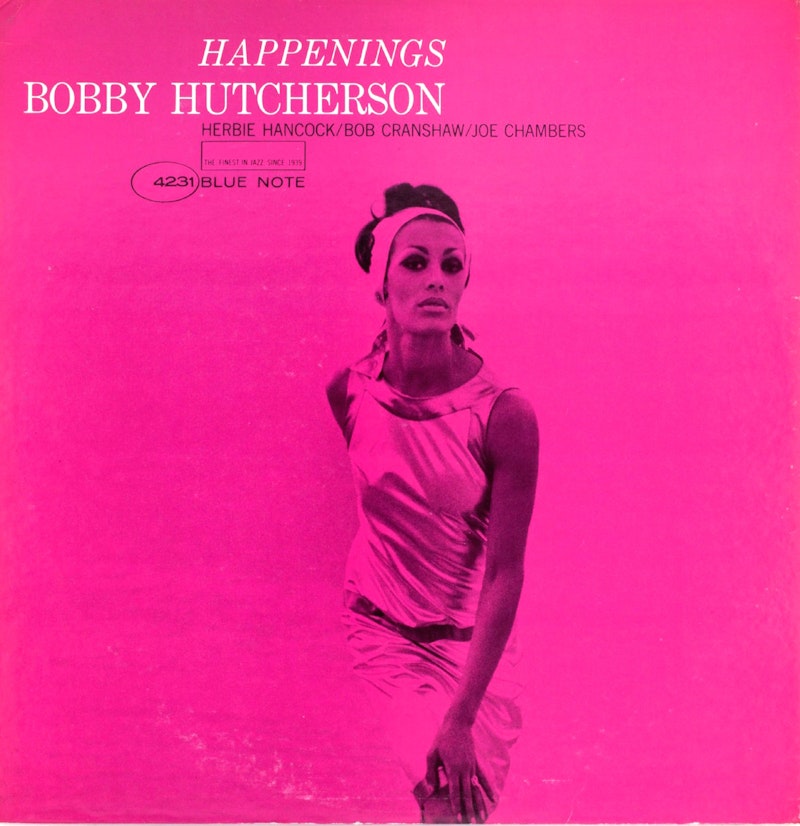

The most dramatic example is the cover art for vibraphonist Bobby Hutcherson’s 1967 LP Happenings. White and black lettering are dwarfed by a translucent wall of hot pink fog. Emerging from the gaudy mass is a woman clad in a sleeveless dress. Her long hair is pulled back as she gazes pensively with an expression that suggests oblique confrontation. Her image barely holds detail as the pink overpowers everything else in this image. The model’s presence is similar to the placement of Happenings closer “The Omen.” Most tracks on this album maintain a familiar post-bop groove; “The Omen” is a grand finale and a grand interruption. The often rhythm-less piece is a trilling blob of melodies produced by Hutcherson’s light speed mallets, and the marimbas, splashy triangles, cymbals, and jittery brushes of percussionist Joe Chambers. Pianist Herbie Hancock and bassist Bob Cranshaw fill in sonic blanks with angular plunks that never overshadow Hutcherson or Chambers.

“The Omen” emerges solitarily from a sturdy sonic backdrop of traditional jazz. By the late-1960s structured jazz compositions had become easy listening; fusion’s proto-prog rock grandeur and the atonal squall of free jazz were all that separated the genre from country club-approved square-ness. More than a super model lost in a psychedelic haze, the woman from the cover of Happenings is an avatar for the state of late-60s jazz and the oblique possibilities of its strange new evolution.

Pioneering pianist/composer Horace Silver never headed too far into the avant-garde fringe. Silver’s seminal 50s/60s Blue Note releases were classic examples of hard bop jazz. His 1962 LP The Tokyo Blues is lush but predictable even though the origins of the set are offbeat. Many of these compositions were written during a Japanese tour. There the artist absorbed the country’s various strains of folk and classical music. Japanese ideas inspired several of Tokyo Blues’ main melodies.

Overshadowing Far Eastern motifs, Silver’s no-nonsense approach is central to everything that’s happening on the album cover and in the grooves. The cover shows him seated in a sun-drenched green space. A piece of Far East-style architecture fills up the background. His facial expression conveys the jovial mood associated with his concerts. Silver’s dressed in contemporary formal attire and flanked by two young Asian women. The girls smile while wearing brightly-colored traditional Japanese garb. Other than faces and hands, their bodies are completely hidden. This image wasn’t meant to arouse or tantalize and these women weren’t part of Silver’s group.

Jazz, rock, and pop records released from the 1950s through the 1980s often used naked or scantily-clad women as eye-grabbing design elements. Sexy cover art sold big, sometimes millions of records regardless of how kinky or aggressive the images were. The cover art from Tokyo Blues is the polar opposite of blatant sexploitation. Silver’s two mild-mannered cover pals only add an element of mystery to the record. They’re not exoticized or eroticized. Teamed with the music’s subtle Asian folk roots, their presence adds a layer of curious contextual garnish to Silver’s oeuvre.

Another person who made it big with Blue Note in the 1950s and 60s was NYC artist Lou Donaldson. The alto-saxophonist’s dance-friendly chug energized some of the earliest known recordings of soul-jazz and jazz-funk. Like his label mates/frequent collaborators Lonnie Smith and Jimmy Smith, Donaldson’s music remains influential in the realms of jam band music, neo-soul, psychedelic funk, and sample-based hip-hop. The artist’s breakthrough track was the title cut from his 1967 LP Alligator Bogaloo.

The trippy cover art for this album can’t be closely compared to the music, but it does complement Donaldson’s work indirectly: two different photos of a model taken from two different angles appear, one superimposed on top of the other. The model is a woman posing jauntily while wearing heavy foundation and thick eye make-up. She wears a long-sleeved, one-piece hooded dress with psychedelic patterns of orange, pink, and yellow. Her head’s covered by a black winter hat that’s partially hidden by the dress hood. Over this image is a transparent close-up of the same woman’s face. Her expression resembles that of the model from Hutcherson’s Happenings—pensive, intense, hypnotic. Unlike that cover girl, this model stares straight ahead. There’s no seduction in the expression, but she might be asking a question or raising an important point. This montage conjures up imaginative scenes from the flashy mod disco-tech milieu that gave Donaldson major pop success. It reminds listeners that this music was once a key component in exciting social adventures, nights on the town dancing and partying amid Fun City’s weird dayglo utopia.