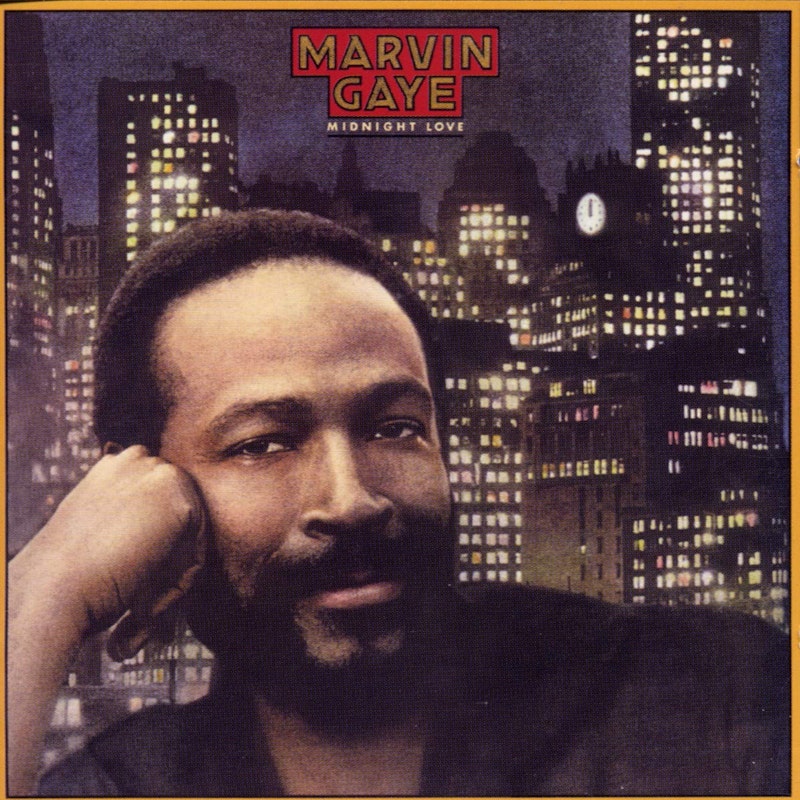

The politically-charged What’s Goin’ On from 1971 and the erotic Let’s Get It On released two years later are widely considered the essential Marvin Gaye albums. Hip crate diggers have recuperated and celebrated later meandering efforts like his post-divorce Here, My Dear and In Our Lifetime. But the album of his I’ve been obsessed with recently is his final one; the 1982 commercial blockbuster Midnight Love.

Critics praised Midnight Love when it came out, though it’s easy to hear why it’s not as celebrated as some of his earlier efforts. Gaye’s classic albums were trailblazing in content and form; What’s Goin’ On, with its multi-tracked overdubs and muzzily crystalline shoegaze soul sounds like nothing else of the era. Midnight Love, in contrast, feels like a capitulation to the zeitgeist. Gaye sings about dancing and love over discofied synth backing. “Sexual Healing,” the biggest hit of his career, is so slight it practically effervesces, the gentle muzak funk nestling into the groove between the Human League and A-Ha. “You’re my medicine/open up and let me in” thrusts into your earhole with a cross-eyed bliss so gentle the entendre drifts into slumber before it can even double.

But if you fall further into that electric boogie, the determined extroverted normality feels weirdly insular. Abandoning Motown for Columbia, this is the first album on which Gaye played almost all the instruments himself, and even (or especially) when he’s ostensibly declaring his affection to some significant other, you get the sense that he’s actually whispering sweet nothings into a cathode ray tube. The ballad “’Til Tomorrow” starts out with a post-coital Gaye asking his girl to stay in bed; when she doesn’t he shifts to incongruously needy and desperate pleading. The music drags and drones as minor-key dissonant synths wash over Gaye’s out of sync harmonies like Vangelis did lots of sad drugs and then slowly disincorporated. It’s perhaps Gaye’s most disturbing ballad, dripping with unmotivated desperation and the not-distant-enough strains of mental breakdown.

The rest of the album is devoted to dance-floor fodder—but here too there’s an ominous undercurrent. The slinky mid-tempo “Turn on Some Music” has multiple Gayes singing and harmonizing around the beat as they moan about listening to “three albums”—it feels like there’s more than one of him inside the room or inside his head. “’Cause music’s been my therapy/taking the pain from all my anatomy” isn’t exactly a comforting sweet nothing; as with “Sexual Healing,” the ostentatious promise of balm could also be read as an admission that something inside has gone seriously wrong.

“Joy” anticipates the proto-industrial thump of Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis’ Janet Jackson productions—funk wound tight enough to drive steel. And “Third World Girl,” which opens with madcap yodeling, herks and jerks through its 4:36 like Kraftwerk marching towards some sort of global erotic dominance. Devo and Talking Heads were supposed to capture the new pop mode of mechanistic alienation. But their more straightforward nerdiness is a pale simulacrum of Gaye’s broken lover man smooth with its fractured social conscience.

Comes a man with a plan to renew the world

Up in rasta land

Hungry boys and girls, ooh

He lived up to his part

And he died with a cause in his heart

Gaye died two years later when he was shot in an ugly altercation with his father. The singer never got to further explore the rapidly morphing landscape of 1980s R&B new electro funk. As a result, Midnight Love’s mostly been treated as a late coda—the twilight of Gaye’s dimming career. It can also be heard as the early hours of a new day, with artificial lights casting a birth of shadows on the dance floor.