This is the most recent post in a series on women filmmakers. The last, on The Heartbreak Kid, is here.

What’s the absolute minimum of cinema, the bit of film that's left when everything else has been squeezed out? The surprising answer? Five minutes of butts.

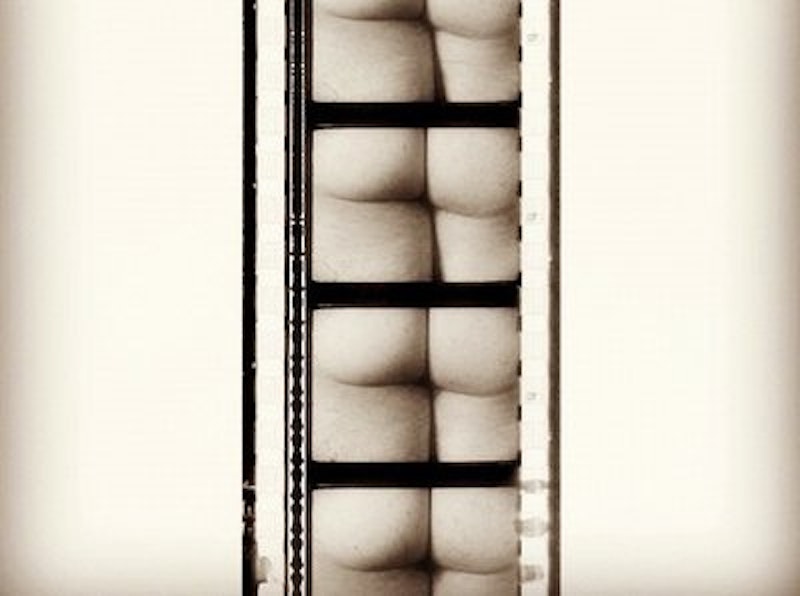

No, I'm not talking about the latest Nicki Minaj music video, but rather Yoko Ono's pioneering, infamous, and silly 1966 avant-garde art piece FOUR (Bottoms). The silent black-and-white film shows a series of close-ups of nude butts, filmed as the butt-owners walk on a treadmill. Each butt is shown for 10 seconds, and the cuts between them are quick and unobtrusive, so you can barely tell where one begins and the other ends. The film cycles through 14 participants, including the butt of Ono.

The film’s been called a motion study, but the focus is so narrow, the perspective so limited, that you can barely see how the movement is happening. The butts almost don't register as butts; they turn into abstractions, flexing and shifting, like one of those flashing Sesame Street videos, though without the color or pizzazz. The bottoms pulse with an irritating restfulness; moving and sitting there both at once. FOUR is an exercise in objectification; the butts are completely severed from their individual bodies. They have, obviously, no personality, and barely any humanity. They’re just moving flesh blobs—scientific curiosities. The objectification is complete, but for that very reason, it's not sexual.

Usually, the camera's gaze upon naked flesh is presented as stimulation; visual pleasure is linked to sexual pleasure. Here, though, you might as well be looking at a chair, or the treadmill itself. The film becomes a kind of lightly mocking parody of pornography. Callously evaluating other humans on the basis of isolated body parts ends up as noticeably anticlimactic when the body parts get too isolated.

Ono removes sex from nudity in FOUR. Even more dramatically, she separates gender and nudity as well. Perhaps a more expert butt observer could categorize the butts into male and female, but it isn't immediately apparent whose rear is whose. Laura Mulvey's gaze theory argued that classic narrative cinema codifies sexual difference, encouraging male viewers to identify with the male protagonist who gazes, and setting women up as sexualized forms to be gazed upon. FOUR doesn't separate the sexes; instead, it makes them indistinguishable. Viewers don't identify with a male or female body. Instead, they look upon universal butts, and are therefore positioned as universal butts themselves. Anyone can be on that treadmill, and any butt is every butt. Bottom looks upon bottom and, with some confusion, fails to recognize itself.

Many who saw the film did hear the call. The five-minute FOUR was succeeded by an 80-minute version filmed in London, featuring a much-expanded cast of celebrities and scenesters. The longer version had a soundtrack, with the celebrities giggling and chatting about the butts and the meaning of it all. The hipster in-joke vibe certainly fits with the original's gently naked provocation, and the implicit utopianism of uncategorized bodies. In that vein, Ono would spend part of her career exploring the borderlands of sort-of celebrity and being famous for being famous. Her embrace of stardom with John Lennon and refusal to make art that read as genius art, rejection along with the public's usual generalized misogyny, led to mass loathing her work. The comments on Four on YouTube are almost uniformly, not to mention arbitrarily, hostile.

Yoko's been pilloried for pretension, but the original FOUR, in the era of social media video, has a familiar low-key charm. As in Penelope Spheeris' Decline of Western Civilization, the punk rock DIY ethos opens up space for women filmmakers who don't have access to the resources and connections needed to make big-budget Hollywood extravaganzas. Male directors are often seen as the normal genderless default, but it's Ono who bares film cinema to its essence. No plot, no characters, no gender, no sex, just some friends getting together for the end of film.