When Joan Watson (Lucy Liu) bitingly asks Sherlock Holmes (Johnny Lee Miller) on the first season of Elementary if he thinks he's the smartest person in the world, he raffishly shrugs, and responds that there's not enough evidence to say for sure.

The joke is that Sherlock’s vain and egocentric; he thinks there's a real chance he's the smartest person on earth. He's considering it as a possibility, rather than as a boast. At the same time, though, there’s something modest about his reticence—and especially about the way in which the show downplays his response. His vanity and its limits are low-key charming.

This is the most striking difference between Elementary's Sherlock and Benedict Cumberbatch's version in the BBC's Sherlock. Cumberbatch plays Sherlock as monstrously egotistical and brilliant—so brilliant, in fact, that he inexplicably has ninja-level fighting skills. The show's high production values are used to turn brainpower into a special effect—as Sherlock deduces, words come up on screen zipping around and showing his logical processes. He's so smart that he sees other people as lesser beings, whose stupidity he cruelly mocks. Cumberbatch’s Sherlock barely knows how to relate emotionally to anyone, and has no interest in sex. His one relationship on the show is revealed to be part of a convoluted plot to snare evildoers.

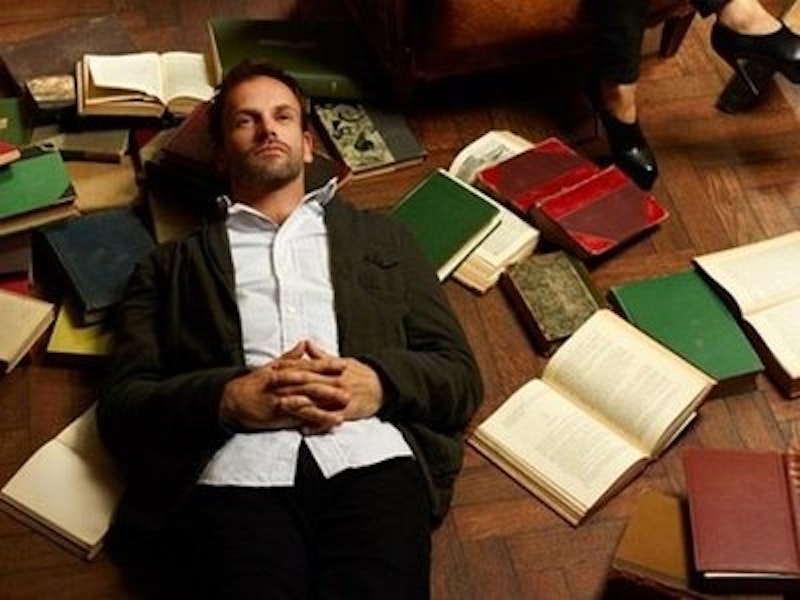

Johnny Lee Miller, on the other hand, is smart and vain, but not superhumanly so. He makes a quip in the first episode about only indulging in sex to fulfill irritating mental and physical needs; he says he indulges the bodily urges to keep himself in top condition, but doesn't enjoy them. But when Watson tells him he's obviously trying too hard to be off-putting, he visibly deflates. In Elementary, Watson not infrequently catches details in a case that Sherlock misses. That virtually never happens on BBC's Sherlock, where Martin Freeman's John Watson really is as far beneath Sherlock mentally as Sherlock says he is.

Cumberbatch's Sherlock is a reflection, supposedly of smart and Sherlock is. Showrunners Mark Gatiss and Steven Moffat write complicated plots within plots with dream sequences, false flashbacks, and cascading revelations, all shot in sumptuous cinematography. The last Sherlock episode of the season involved Sherlock re-remembering a sister he'd forgotten. And who’s the sister? She's both a villain and a scared little girl trapped on an airplane. If that sounds like it doesn't make a whole lot of sense, that's just because you're one of those inferior humans who doesn't understand cable television.

Elementary, on CBS, doesn't have Sherlock's sweeping ambitions. In each Elementary episode, Sherlock solves a murder. And that's it. The murders are tricky; there are false leads and improbable twists—the blood sample DNA wrong because the murderer was a leukemia patient who got a bone marrow transplant is a particularly preposterous example. But the show never tries to trick you into thinking reality is a fantasy, or vice versa. It's a network mystery show. It has no bigger purpose.

And the willingness to just be pleasant television makes Elementary not just more honest, but more insightful. In Sherlock, the viewer’s told over and over that the relationship between Holmes and Watson is transcendent, but it's never very convincing. Holmes is too much of a jerk, and Watson is too much of a doormat. They'd never stay together—and the show throws itself into wearying contortions trying to explain why they would.

In the first season of Elementary, on the other hand, Sherlock is a recovering addict; Joan is paid by his father to serve as a sober companion. The two have some static at first, but over time, Sherlock grows to appreciate Watson's competence, and also her intelligence and professional knowledge, since she used to be a surgeon. For her part, Joan finds she enjoys puzzles and detecting. Their professional relationship turns into friendship because of growing mutual respect and shared interest.

I don't mean to make great claims for Elementary. It's formulaic, not revelatory. But it doesn't have to be the best show—nor even the best Sherlock Holmes show. It's willing to let its characters be small as life. And so, by a clever but quiet twist, it is in fact the best Sherlock show. Sometimes you come up with a superior solution when you're willing to admit you don't have all the answers.