The friendship—the kinship, some might say—of auteur directors Robert Rodriguez and Quentin Tarantino has been documented extensively and exhaustively. The pair shares a love of cruddy, low-rent grindhouse cinema. They have acted in or scored or produced one another’s movies. They’ve co-directed movies. They have held film festivals featuring gruesome 70s exploitation flicks at one another’s homes. One imagines that the two men share other common interests, but lately I’m starting to think that Tarantino’s motives for nurturing this brotherhood are less than pure—namely, that the haphazardly slapdash nature of Rodriguez’s adult films is such that Tarantino’s own genre-derivative-but-way-cannier pictures benefit from the association, that in comparison to the willy-nilly noise and gore-y anarchy of, say, Planet Terror, Death Proof is on some sublime Jean-Luc Godard plateau of cohesion and wiliness.

Whether or not I’m right about this, it’s beyond debate that Rodriguez’s post-Desperado non-Spy Kids projects are ambitious to a fault, cramming dozens of narratives and backstories and firefights and bullshit popcorn catchphrases into two-hour time-frames. In the past, I’ve been able to enjoy these abominations despite themselves: dynamite casting and trash culture glee made the watching-through-ones’-fingers zombie-ooze grossness of Planet Terror bearable (if only for one viewing), while Johnny Depp’s laconic DEA agent justified Once Upon A Time In Mexico enough that I caught it in the theater and bought it on DVD.

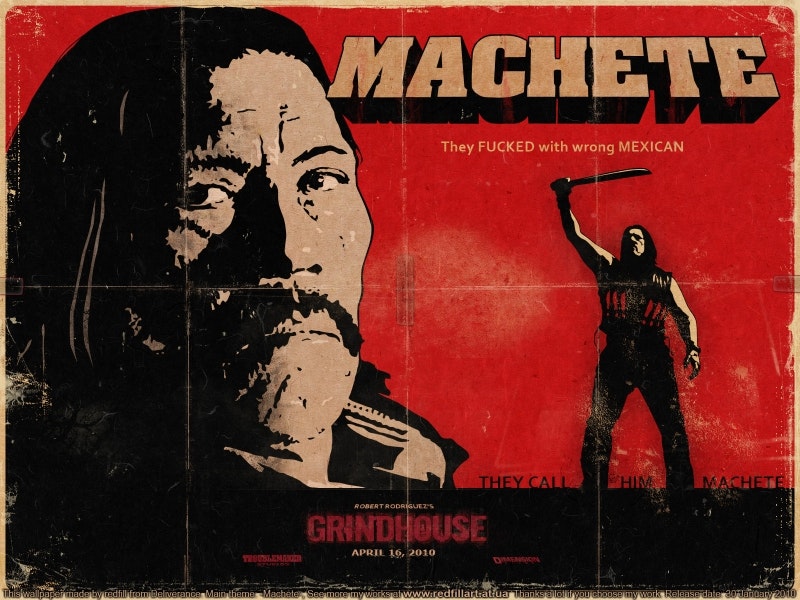

Not so with Machete. As an idea whose time should’ve come some time ago, it’s hard to shout down “Mexsploitation,” and the immigration-battle-lines-drawn theme is one Rodriguez can milk endlessly if he opts to build a franchise around Danny Trejo’s grizzled, scared visage. But I’m not certain that Machete was worth mid-wifing beyond an arresting trailer sandwiched between Grindhouse’s two halves. In signing out of polite society and buying into the sheer, mindless ridiculousness of the whole Machete enterprise, you co-sign for stunt-casting run rampant—Steven Segal turning himself into the butt of the joke as a drug kingpin, Don Johnson gunning for illegal immigrants, Robert DeNiro in a role too ridiculous to explain—but these performances never achieve anything beyond surface-level shock and aw-Hells-naw, seasoned vets slumming and chewing scenery for kicks.

As the plot (and Trejo, who’s less an actor than a monstrous presence) creaks forward and everything grows more and more convoluted—the anti-immigration congressman employs an aide who’s in cahoots with a drug lord, but the aide’s daughter is an online porn queen, and Machete’s brother is a priest, and Michele Rodriguez looks as fetching in an eye patch as Rose McGowan did in Planet Terror, and on and on and on—the viewer starts to pity everybody involved, to wish the thing over and done, already. Depending on one’s tolerance level for schlock, this feeling may kick in as early as the movie’s first third. Two minutes of Lindsay Lohan was more than enough for me, but I could have gone for more Cheech Marin and less Jessica Alba. Jeff Fahey, meanwhile, presented such a shiftily multi-faceted portrait of evil that his character deserves his own movie. In between such hamming, the gross-outs—don’t ask where that naked babe in the opening retrieved that cell phone from—and gore-y set-pieces come so fast and furious that one becomes numb to them, if their opposite numbers in Mexico hadn’t done the job. Lives are without value; deaths often aren’t really deaths. It’s flash and fury, signifying nothing more than flash and fury.

Among the dangers Machete faces is this: Trejo is old, like really old, and his expressiveness as a screen actor rivals that on a pile of freshly chopped wood. Because of this, arresting cinema must be built around his bulk in order to draw us into the world of a less-than-dexterous protagonist whose choicest witticism is “Machete don’t text.” Rodriguez, needless to say, tries too fucking hard, building a skyscraper of chaos, legends, gunfire, and bare, supple flesh where a brownstone might have sufficed. I’m sure Tarantino, whose Inglorious Basterds, comparatively, was a model of restraint, was pleased as punch, for reasons simultaneously wrong and all too right.