Fireworks, flowers, rainbows and sunshine. These are poetic images synonymous with love and lust yet more often than not intimate sexual experiences transpire with eyes closed in the dark. Numerous medical and psychological studies have been conducted by scientists trying to understand the connection between darkness and romance. The common consensus: passion and physical stimulation reach their loftiest heights without visual distraction. Deprived of light, the brain is forced to focus on the complex response of nerve endings more than anything else. Only when earthly visions disappear can people fully enjoy the rush of ecstasy.

Veiled references to the relationship between intimacy and darkness turn up in a handful of classic fantasy films made during Hollywood’s freewheeling pre-Hays Code days (i.e., jungle horror epic Island of Lost Souls, the DeMille musical Madame Satan, and the original 1931 Dracula), but it’d be the late-1960s before cinema built entire narratives around the symbiosis of deep voids and passionate embrace. In Roger Vadim’s 1968 film Barbarella outer space was a conceptual boudoir illuminated by a mystical supernova of sexuality. It was based on a comic series created by Jean-Claude Forest which was first published in 1962 in the French adult magazine V. Webzine Hollywood Comics ran a comprehensive retrospective tribute to Barbarella that cited the character’s defining trait as “a fragile yet invincible aura,” The seductive space-traveling peace keeper’s print adventures remained immensely popular during the 60s even after the French government banned any public display of a 1964 graphic novel version of her exploits.

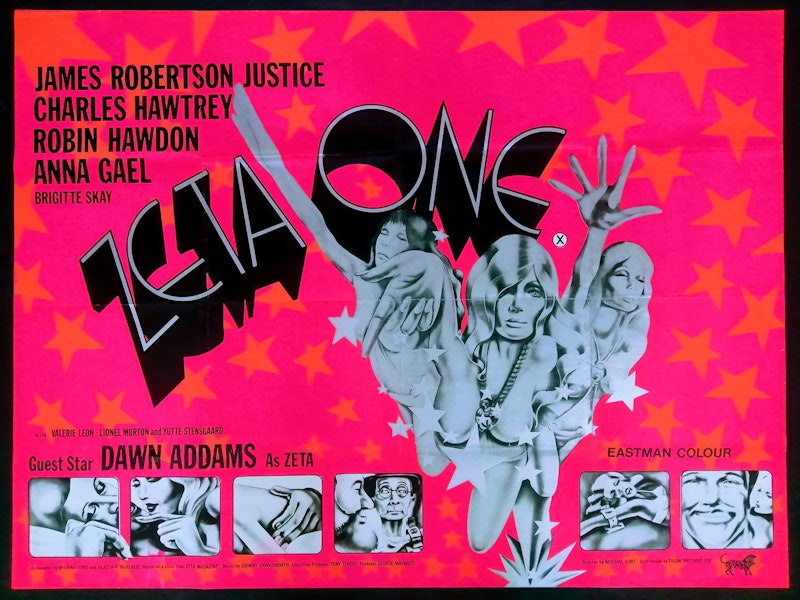

The Barbarella film was an arty blockbuster that launched a new sub-genre of erotic sci-fi films and its title character became cinema’s first major sexual superhero. The movie’s imitators came in many shapes and sizes. Some were nothing more than dopey camp fests. 2069: A Sex Odyssey, Zeta One, The Girl From Starship Venus, and other sleazy romps were typical sexploitation programmers dressed up in silvery cosmic underwear and cardboard space scapes. Other more eccentric/big budget works managed to match the ambition of Vadim’s opus. The best of these included Hammer Studios’ provocative “space western” Moon Zero Two, the grotesque satire Flesh Gordon, and avant garde/cut-and-paste classic Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women. Many other steamy sci-fi films and TV productions of the Vietnam era existed in the middle ground between cheesy and challenging. Regardless of pretensions or budget size, they all revolved around the concept of outer space as a nexus for eroticism.

The stellar expanse served as a perfect counterpart for the un-seeable sex energy that drove Barbarella and similar works. Like a romance, outer space can be mercurial —a desperate icy bastion of loneliness one minute, a vaunted frontier for adventurers and idealists the next. The Milky Way’s swirling colorful textures inspire awe and curiosity. The lunar cycle can bring out the beast in humanity; it can also symbolize idyllic beauty and the cycles of reproduction. In each case, cosmic phenomena energize feelings of excitement and romance. These phenomena reach their peaks of power when the sun goes down and the moon comes up. An infinite background of pitch black frames the galaxy, always clinging, always there to remind us of the darkness where love and intimacy can burn as bright as the stars.