Chris McKim’s documentary Wojnarowicz: F**k You F*ggot F**ker presents us with a remarkably prescient writer and artist. In a career that spanned about 12 years, David Wojnarowicz was highly prolific and adaptive to different media, an artist whose persistent state of finding different ways to express himself left a treasure trove for biographers. Wojnarowicz’s work is often described as “rooted in rage”—rage at his abusive parents, and rage at a system turning its back on the AIDS crisis. What becomes clear is that he’s no victim: this is a man who dedicated his life and work to kicking against the pricks.

McKim makes extensive use of Wojnarowicz’s recorded diaries to provide narration. This is an effective device: letting the artist speak for himself, so that when friends and family are introduced, they’re used to provide context for the time in which he lived, and to fill in some necessary blanks. This is certainly the case with his friend Fran Lebowitz, whose strong personality could’ve easily overwhelmed the film. She does a great job of describing the promiscuity of pre-AIDS New York, and the prevailing attitude that sex was good for you and sexual repression was bad. In addition, her assessment of how small and insular the East Village art scene was around 1980 (“You could fit everyone into one restaurant.”) sets the stage for why Wojnarowicz came to view the art explosion later in the decade as something of an intrusion.

Cynthia Carr, author of the biography, Fire in My Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz, is underutilized by comparison. In listening to other interviews prior to the film, she is the expert in all things Wojnarowicz. Her 2018 interview with the Hyperallergic podcast does a better job of providing a more linear timeline to a brief life with so many twists and turns. In addition to Carr, I would have liked to have heard more from collaborator Jesse Hultberg (who now hosts his films on YouTube).

As a multimedia artist who often had several projects moving concurrently, it’s easy to get lost in the flood—and what’s missing is that he was always writing, publishing two books during his life, plus four more posthumously, in addition to numerous essay and article contributions that continue to show up in assorted anthologies. Going by the film, one comes away thinking Wojnarowicz wrote just the one book about street kids in Paris when he was 20 and some occasional essays. This belies the fact that Wojnarowicz initially thought of himself as a writer.

Wojnarowicz had a notoriously difficult life, and McKim respects his dignity enough to never entertain any fatalism. Growing up in an abusive household, Wojnarowicz’s brother said that he never saw any artistic inclination, but then again, they were too focused on survival. By the time he was a teenager, Wojnarowicz had come to prefer life on the streets of New York to home, and took to hustling and turning tricks to get by. He also did a fair bit of traveling, and the film shares his earliest known tape recordings, where he waxes poetic about hopping freight trains across the country. After following his sister to Paris, he takes up permanent residence in New York in 1980, and this is where both the film, like his career, really take off.

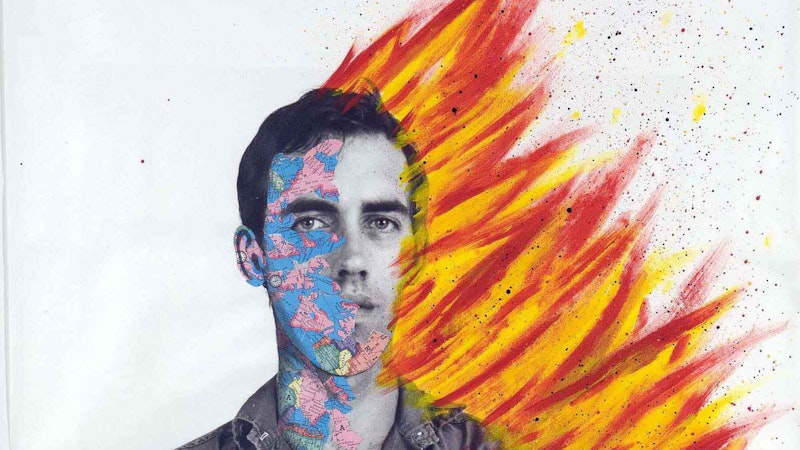

Despite almost no training, Wojnarowicz had an extensive knowledge of the arts and tremendous ambition. In his earliest work, spray painting stencils into graffiti art, he was already establishing motifs that would characterize his art: the burning house, the gagging cow, the urban guerilla. Adept at making use of anything he could find, his first show in 1982 saw him recycling discarded grocery signs, trash can lids, and driftwood into ad-hoc canvas. The early result was a kind of feral pop art that would only get more and more confrontational.

The most significant event of Wojnarowicz’s life and career was meeting photographer Peter Hujar. A brief romance turned into an intense friendship and mentorship. In Hujar, Wojnarowicz saw the principled, working artist that he longed to be. Hujar helped him quit drugs and guided him into galleries. After Hujar’s death from AIDS, and his own diagnosis, Wojnarowicz came to view his art as acts of civil disobedience, especially his attacks on religious hypocrisy. An acquaintance described it as “not gay as in I love you, but queer as in fuck off!” He would become a target for operatives rallying the religious right to interfere with his NEA funding. Wojnarowicz would successfully sue them for copyright infringement, winning $1.00.

Wojnarowicz’s chronicles of the AIDS crisis have a lot in common with our own era of misinformation. His descriptions of political tribalism, particularly as it relates to racism and homophobia, remain relevant. His concept of “the pre-invented world,” where we are born into a world that values conformity to arbitrary social structures by denying the natural self, has a relationship to contemporary discussions of othering and dehumanization. McKim does a great job of showing us that as much as Wojnarowicz was a man of his time, he could also be, nearly 30 years after his death, an artist for our time.