This is part of a series on 1980s comedies. The last entry, on Raising Arizona, is here.

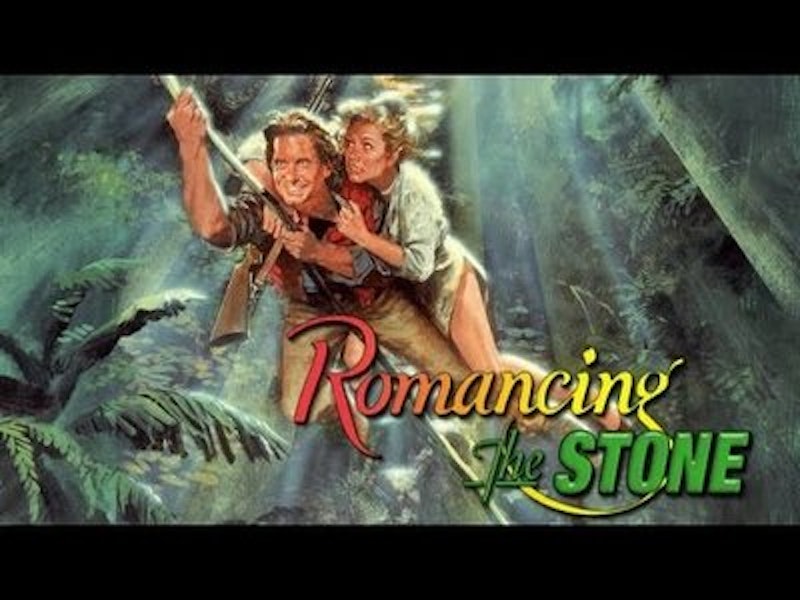

Romancing the Stone (1984) is an exhilarating romcom in part because it so unashamedly treats love as liberation. The film’s firmly and consistently told from the perspective of its female protagonist, romance novelist Joan Wilder (Kathleen Turner). And while it occasionally teases her, it never sneers or—a la John Hughes—revels in her humiliation. Instead, Turner and director Robert Zemeckis exult in Joan's transformation from mousy romance novelist to resourceful adventuress—while suggesting that she was always more resourceful than she was willing to admit to herself.

There's one problem. Joan's triumphant self-discovery is enabled by her journey into the heart of darkness—in this case, Colombia. Joan is a wilting white flower until she goes abroad and divests herself of the stifling strictures of Western (patriarchal) civilization. Feminism is exciting and fun in Romancing the Stone in part because it’s imperialist. Joan gains power specifically by gaining power over people of color in the global south.

The film starts in New York, where Joan’s just finished a Western historical novel starring a manly adventurer and a fierce, knife-wielding heroine. Joan's own life is dull and cloistered. Things pick up, though, when her sister's husband is murdered in Colombia shortly after sending Joan a mysterious map. The sister, Elaine (Mary Ellen Trainor), is soon kidnapped, and her abductors demand that Joan come to Colombia with the map as ransom.

Joan flies to Colombia, which, in the film, is a barely civilized den of iniquity and death. While there, Joan’s stalked by a mustachioed sadist named Colonel Zolo (Mauel Ojeda). She also falls in with a raffish American, because only Americans can be heroes. Jack Colton (Michal Douglas) hacks off the lifts in Joan's high heels, eggs her on to find the treasure, teaches her to dance, and comes to her rescue at the film's end—or tries to. She is, by that point, able to rescue herself.

As in Joseph Conrad, the jungle doesn't change Joan so much as it shows her what's inside her—though in this case that isn't so much an existential lust for death as it is sexy self-confidence. When Joan and Jack discover a downed drug plane in the jungle, Jack’s shocked that Joan recognizes the marijuana cargo. "You smoked this?" he asks. "Sure. I went to college," Kathleen Turner responds with a perfect off-hand deadpan. She's unexpectedly at home in this adventure; she's been on such trips before.

Even more telling is Joan's popularity in Colombia. When Jack and Joan stumble into a tiny village run by drug runners, they discover, to their befuddlement, that the leader of the gang—played by a delightfully manic Alfonso Arau— is a huge fan of Joan's novels. He reads them out loud to his henchmen in place of telenovelas. The noble manly men and daring heroines of Joan's imagination fit right into Colombia; her brain was there in spirit long before her body showed up.

Jack doesn't teach Joan to be adventurous; he watches in delight as she crosses rickety bridges over terrifying gorges, or deciphers that map. "All right, Joan!" he shouts after she performs a particularly unexpected feat, neatly summarizing the message of the film.

Colombia brings out Joan's wild woman—which, unfortunately, means that Colombia is defined in the film by its danger, and distance from civilized norms. Colombia is so busy brining out the better woman in Joan that it doesn't have any room for the women who live in the country. Joan fights hairy, sweaty Colombian men, but Colombian women barely exist. No woman of color has a speaking part in the film, and they’re almost never glimpsed even in the background. Feminism in Romancing the Stone means self-actualization for some women, and erasure for others.

Locating feminist self-actualization on the imperial border isn't new. In her book Beyond the Pale: White Women, Racism, and History, Vron Ware notes that middle-class white women in England often saw teaching or missionary work as an escape from the stifling patriarchal confines of sexism in England. Women were granted power, scope and freedom as long as they were willing to do the work of imperialism.

Feminist empowerment for white women has, historically, been predicated on placing themselves in a milieu where race overshadows gender. It's not a coincidence that Joan becomes cool, sexy, and exciting by finding and stealing an enormous emerald from the Colombian authorities. Romancing the Stone is significantly better written, better acted, and less viciously racist than Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, released the same year. But it shares an uncomfortable conviction that "empowerment" means "colonial expropriation."

Oppression is confining; when you're not free, you can't move. Romancing the Stone maps liberation onto space. As a woman, to escape the confines of patriarchy, Joan has to go somewhere else. The problem is that the "somewhere else" is inhabited.

And if the stone is freedom, Joan takes it from them.