I was 10 when I first discovered The Who’s Tommy. I rented the cassette tape of the 1975 movie soundtrack, and fell in love with the story of the deaf, dumb, and blind boy who could play a mean pinball. Four years later I watched the movie, and hated it. It was over-the-top and confusing. Luckily I bought the original 1969 Who album shortly after, which washed the awful taste of the movie out of my mouth. It’s still one of my all-time favorite albums.

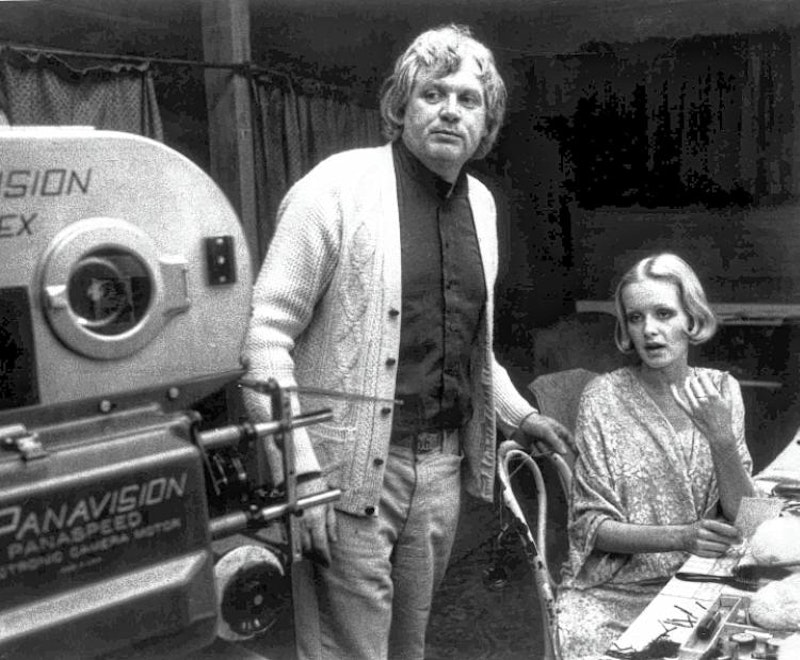

Now almost 35, I’ve grown to appreciate director Ken Russell’s cinematic interpretation of Tommy. Not only did he bring Pete Townshend’s vision to life, but also added his own interpretation to the story. Tommy tells the story of a boy who becomes psychosomatically deaf, mute, and blind after watching his father kill his mother’s lover. He experiences the outside world through vibrations, and his parents subject him to the abuse of his Cousin Kevin, Uncle Ernie, and the Acid Queen. Despite his disability, Tommy becomes a pinball champion, and when he finally regains his senses he’s hailed as the new messiah. Unfortunately, he abuses his power, his followers disown him, and the story ends with Tommy realizing true enlightenment comes from within.

Russell’s movie mostly sticks with the original plot, but adds a few changes. In the movie the mother’s lover kills Tommy’s father, which Russell felt would be more traumatic for Tommy. I agree because throughout my childhood, I always felt threatened by my mother’s boyfriends, so having the lover kill the father taps into that fear many children have of the evil stepparent.

Another change Russell made was to turn the Hawker from “Eyesight to the Blind” from the Acid Queen’s husband/pimp to the leader of a religious cult that worships Marilyn Monroe, with booze and pills replacing bread and wine for communion. According to the 2004 DVD commentary, Russell was developing a movie idea about false religions around the same time he was approached to direct Tommy, so the “Eyesight to the Blind” sequence is a commentary on celebrity worship. He continues this idea throughout the film following Tommy’s rise to fame first as a pinball champion and then as the new messiah. In fact, Tommy’s new religion revolves around pinball; his logo is a T with a pinball on top, and he instructs followers to find enlightenment by playing pinball with their eyes, ears, and mouths covered. Russell and Townshend’s message is clear: don’t blindly follow leaders (no pun intended), and find the truth within yourself.

Russell’s films were often criticized for the use of hyperbolic imagery, and Tommy’s no exception. The movie’s filled with such surreal imagery as the Acid Queen’s iron maiden full of syringes, the Pinball Wizard’s tall boots, and Anne Margaret rolling around in a pool of beans, soap, and chocolate. After watching some of Russell’s other films, I realized this was his style: interpret music with surreal images. For example, his movie about Gustav Mahler opens with a woman coming out of a cocoon, and features a weird fantasy segment comparing the composer’s conversion from Judaism to Catholicism to making a Faustian deal with a Nazi woman.

Tommy has flaws. Oliver Reed can’t sing worth a damn, and the soundtrack could’ve used fewer synthesizers. Despite its imperfections, though, Ken Russell still managed to take The Who’s famous rock opera and turn it into one of the best rock ‘n’ roll movies of all time. He captured Pete Townshend’s vision while at the same time putting his own unique stamp on it. I wish I’d recognized it sooner.