There isn’t a single movie released in 2021 that had as much of a botched release as Guillermo del Toro’s Nightmare Alley. When I saw it coming up on theater calendars, I thought the 1947 version with Tyrone Power was being revived. I never saw a trailer for it at any of the theaters that ended up screening it, and only after the new year did five-second YouTube ads start appearing. I really liked The Shape of Water, and while he’s not a genius, I don’t think Del Toro deserves the kind of middlebrow dismissal that he often gets from snootier critics. What was so impressive about The Shape of Water was precisely what everyone made fun of: Sally Hawkins fell in love with a sea creature, and it made sense. He made it work without it ever being silly, far from it—to my astonishment, I was holding back tears at the end of that movie. And they made love in Baltimore’s Inner Harbor (in the early-1960s; presumably, a hospital visit was not required afterwards).

The Shape of Water won Best Picture at the Oscars in 2018, and del Toro’s new(ish) movie—not a remake of Edmund Goulding’s film, but a faithful adaptation of William Lindsay Gresham’s long, dark, and complicated 1946 novel—might spell the end of Searchlight Pictures, the studio formerly affixed with Fox and currently in the hole for $45 million on the production budget alone, forget about advertising. As a Hail Mary, they’ve re-released Nightmare Alley in black and white in 1020 theaters, promoted with the corny carnival subtitle “Visions in Darkness and Light.” I’ll blow the bugle and say this movie is great, and this version is worth seeing while it’s in theaters.

There’s no way this movie looks better in color, not only because del Toro and cinematographer Dan Laustsen lit it with black and white in mind (like Peter Bogdanovich and László Kovács with 1976’s Nickelodeon, a flawed film that remains one-note and boring in any color), but because Gresham’s novel can finally be adapted without elision or censorship. Del Toro’s Nightmare Alley is a noir—not a neo-noir—where peoples’ noses are punched into their skulls, with fountains of blood and no sight spared when dealing with the “freaks” that run the carnival. We begin with the image of Stan Carlisle (Bradley Cooper) picking up a wrapped body, throwing it into the open floor, and following it up with a match. Cut to the carnival: Carlisle is a born carnie and a huckster with dreams of bigger schemes, but he has to start somewhere.

Carnies played by Willem Dafoe, Clifton Collins Jr., Ron Perlman, Toni Collette, and David Strathairn put Carlisle through the ringer, and soon after seeing his first “geek feast”—as Dafoe puts it, the “geek” is a delirious alcoholic you can lure in off the street with a couple of shots spiked with drops of opium, and once they’re hooked, you can lock ‘em up and make them eat live chickens in a pit for a paying audience—well, Carlisle is hooked, but he knows he has to get out. He convinces Molly Cahill (Rooney Mara) to come with him, and after some hesitation, she agrees, and within two years, they’ve become successful “mentalists,” just another passing fad that will make them rich and surely be their downfall.

Nightmare Alley looks fantastic in black and white, and at 150 minutes, never drags, unlike so many other recent movies bloated beyond capacity. It looks a lot better than Belfast or Roma, for example, and just as black and white once helped sell actors in certain roles they were far too old for, what the black and white does here is mask all of the lousy CGI that blemishes del Toro’s films. There aren’t many special effects heavy sequences anyway, but when things explode, catch fire, or people are shot or beaten to death, it looks more real than it ever could’ve in color. Considering how dark Gresham and del Toro’s screenplay (co-written with Kim Morgan) get, this is the version that should’ve been released first. Why not? Del Toro’s last movie won Best Picture—there isn’t a bigger blank check than that in Hollywood.

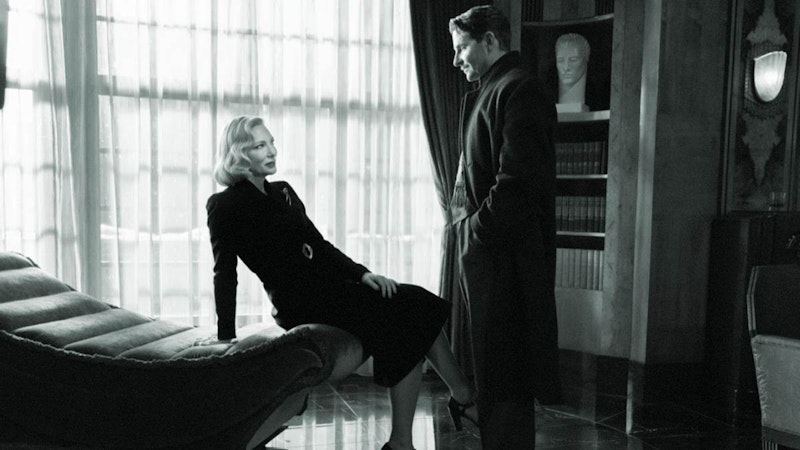

Richard Jenkins is phenomenal as Ezra Grindle, a member of New York high society and, according to Carlisle’s new psychiatrist mistress Lilith Ritter (Cate Blanchett, in a good but routine performance), “someone you don’t want to cross, because if you flop, it’ll be the end of both of us.” By the time Carlisle and Cahill, as Grindle’s murdered lover Dory in an “apparition,” meet in a snowy graveyard, it becomes obvious why Gresham’s book was never properly adapted. “I’ve hurt so many women,” Grindle tells Carlisle, believing in his “mentalist” powers completely, and Ritter correctly guesses that Carlisle was molested by his alcoholic father, the man he buries and burns in the first shot of the movie. Grindle runs to “Dory,” and after realizing it’s not the ghost of his dead lover, but a stranger, he vows to “destroy” Carlisle right before Carlisle destroys him, with several hard blows to the nose that makes his entire face cave in. Del Toro dollies in on his blood and brains spilling out of his skull as Carlisle and Cahill back up and run over Grindle’s ever loyal bodyguard. And then they’re out of there, free.

They don’t get very far together.

There’s no subversion of the genre or significant difference in form; the only thing separating del Toro’s Nightmare Alley from the films of the 1940s and 1950s is its explicit content. This is a major achievement and a successful, risky experiment. If Searchlight survives the film’s commercial failure, it’ll be a while before they put out anything as assured and disturbing as this.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith