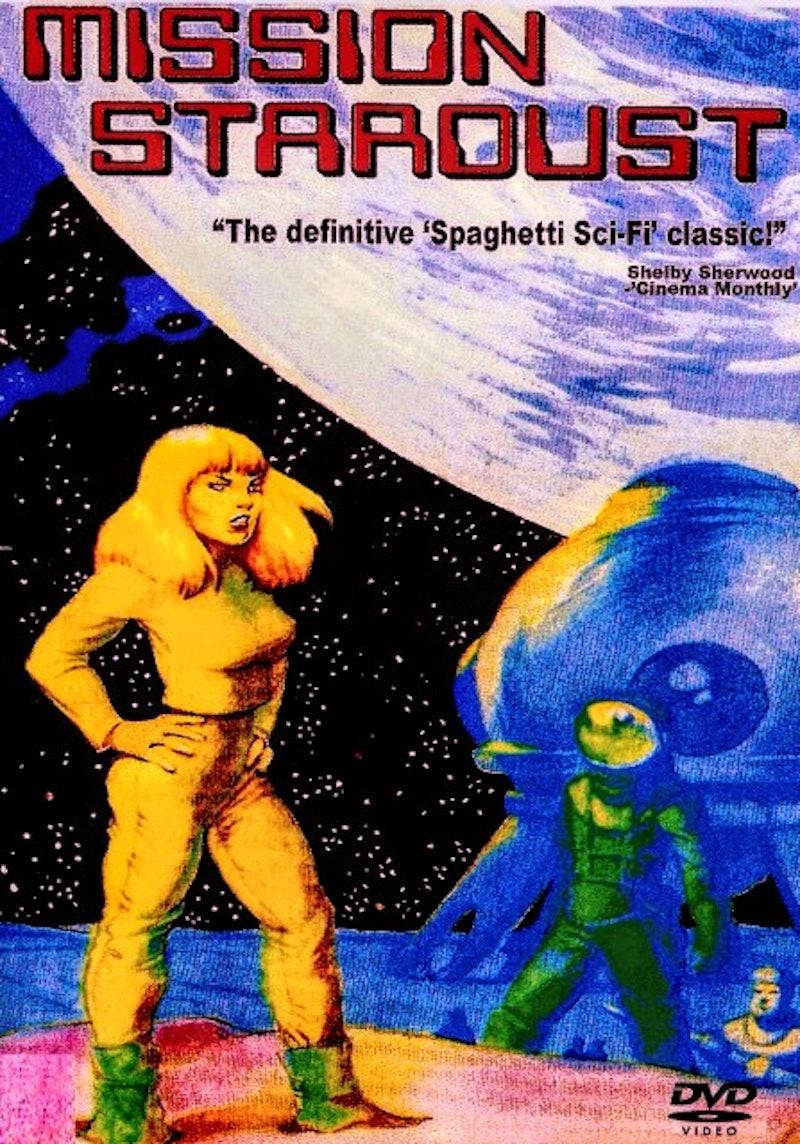

Avid readers of vintage science fiction mainly know Mission Stardust as the cinematic debut of Perry Rhodan, an “immortal grand administrator”/“peacelord” who travels through time and space protecting oppressed beings throughout the solar system and beyond. Rhodan is the main character in a pulpy novel series that’s run continuously since 1961. In their Vietnam era heyday, these books were beloved all over the world, but inconsistencies between the written and film versions of the character disappointed longtime fans. Unlike his literary persona, time travel and supernatural omnipotence were not part of his on-screen identity. Instead, Mission Stardust awkwardly mixed the book’s tangled narratives and mystical idealism with alpha male histrionics reminiscent of James Bond and other iconic action heroes. The 1967 film came from a time when fantasy works of all shades had just begun to attract more politically conscious audiences beyond the genre niche.

This Italo-German co-production was a confusing gauntlet of sci-fi, drama, sex, and political intrigue set to a zoned out score by Antonio Abril and Marcello Giombini. The cosmic folk rocker "Seli" wails as the opening credits roll accompanied by swirling Fillmore-ready pulsations of light. At the heart of the story we find a NASA-like organization sending Perry Rhodan (the ass kicking/square jawed Lang Jefferies) and his astronaut crew on a lunar reconnaissance mission to search for natural resources. Upon arrival they’re confronted by the shipwrecked Arkonide aliens Crest and Thora, who command a clunky robot infantry that bears close resemblance to Doctor Who arch-foes The Sontarans.

The frail middle aged Arkonide man Crest is a subordinate crew member suffering from leukemia. Thora is the tough-as-nails commander of the ship; she’s played by Swedish starlet Essy Persson, a glamorous performer better known for her work in Radley Metzger’s 1960s sex films and the British political horror Cry Of The Banshee. Thora’s characterization is a schizoid pastiche of feminist innovation and sexist/heteronormative fantasy. One minute she’s a macho poker-faced military strategist, the next she’s randomly flirting and stripping her clothes off in front of Rhodan. They share numerous moments of absurd sexual tension. Those scenes are inconsequential, probably the creative contribution of a misguided studio bigwig who felt extra sex appeal could be a selling point.

Rhodan has close ties to a renowned Kenyan cancer specialist named Doctor Manoli. After the space explorer brings the Arkonides to Kenya, he then heads off to bustling Mombasa to convince the doctor to provide free medical care for Crest as an interstellar goodwill gesture. A mega-powerful crime boss gets involved in the whole mess embedding secret operatives among Rhodan’s crew and Dr. Manoli’s staff. The plot points just pile up and get more random from then on. Luckily, that narrative sloppiness can’t stop Mission Stardust from being a visually powerful work. The phantasmagoric atmosphere came courtesy of effects wizards Antonio Margheriti (long before he became the gore-god behind Cannibal Apocalypse), Antonio Bueno, production designer Giorgio Giovannini, and cinematographers Manuel Merino and Ricardo Pallottini.

Their hallucinatory powers peak when the aliens get a not-so-friendly welcome from Earth’s military forces soon after arriving in an African desert near the outskirts of Mombasa. The arid rocky backdrop looms in shades of rust, ochre, and dark beige that contrast an endless blue sky and the metallic sheen of the Arkonides’ multi-colored spaceship. Dusty plains ring with noise from pompous xenophobic officers barking out orders that no one can complete as Thora uses futuristic weaponry to make short work of attackers. The Kenyan army officers are all portrayed by white Europeans while the infantry men they command are black Africans. This could be part of a thinly-veiled anti-colonialist reference; Kenya had only been free from British rule for about five years before this film was made and it’s not uncommon for imperialist overseers (and their paternal condescension) to linger during a transference of power. The white Earthling army commanders appear grotesque and villainous; their sweaty furrowed brows glisten in the sun, faces blush and twist into shapes of rage. The story’s best anti-imperialist intentions are revealed as Thora reduces the men to a dusty pile of bent-up scrap metal and shredded fatigues. Her power as a sex symbol and her power as an alien contrast the ugly weakness of the archetypal macho military.

Thora’s initial characterization as a gruff cynic and the gradual development of the aliens’ alliance with Rhodan turn the “Earth vs. UFO’s” trope upside down. The aliens not only become protagonists, but also sympathetic victims forced to defend themselves against unjust persecution as the Earth army’s foiled attacks were born only of fear and ignorance, two things that fueled the rise of the military industrial complex, Nazism, Apartheid, America’s anti-segregation movements, and other late-20th century political disasters. Wise‘s touching sci-fi “message movie” The Day The Earth Stood Still outlined similar themes in a more focused way, but the conceptual chaos of Mission Stardust is much more interesting and eccentric, a humanistic dayglo rant destined to be debated for eons to come.