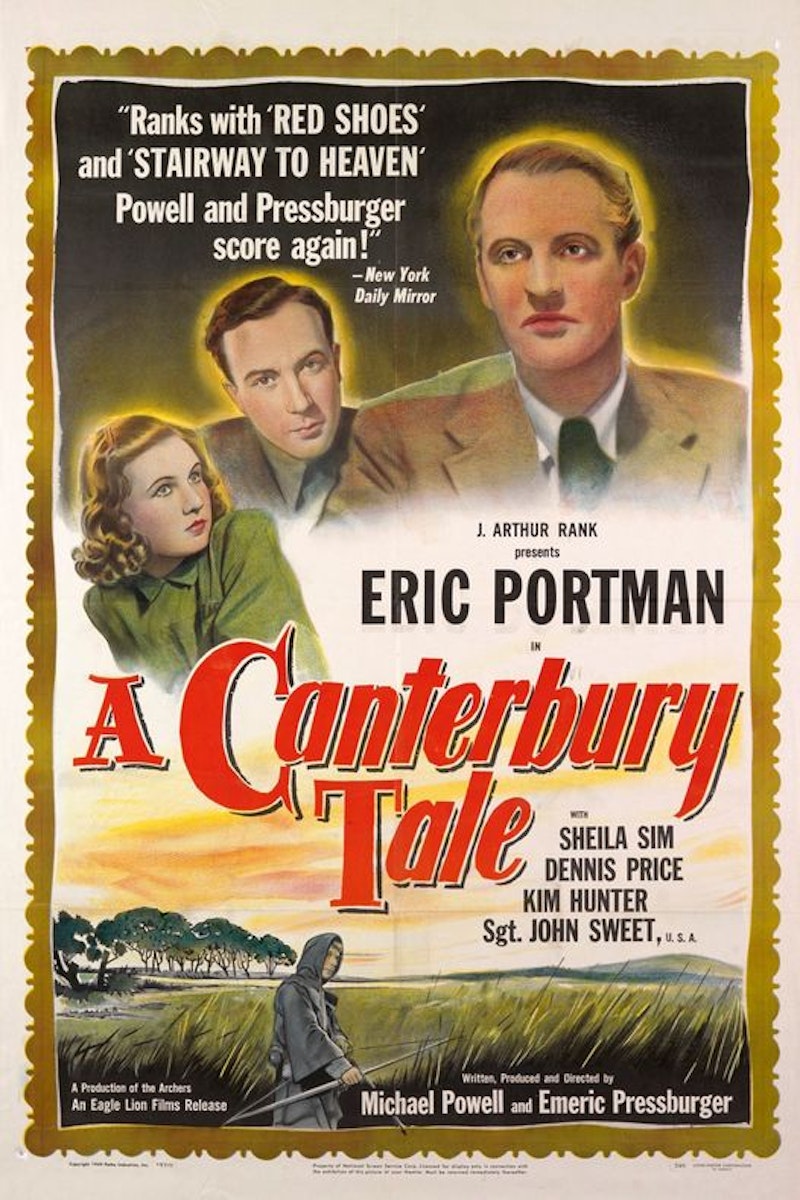

A Canterbury Tale is a weird old propaganda film of the 1940s. It was made by the filmmaking team of Michael Powell and Emeric Pressburger, who also made The Life and Death of Colonel Blimp, A Matter of Life and Death and Black Narcissus, among others. It can be found on YouTube and is worth watching, especially for a Canterbury audience, as it includes contemporary shots of bomb sites along Canterbury High Street, where the film comes to an end. It’s a strange mix: part mystery, part history, part spiritual quest, and much of it was shot in and around the villages of Kent, which gives the film a romantic, nostalgic feel.

The plot is ludicrous, involving a mysterious “glue-man” who pours glue over women’s hair after dark. The three central characters meet on the station platform of the fictional Kent village of Chillingbourne (an amalgam of Chilham, Fordwich, Wickhambreaux and other villages near Canterbury). They consist of a British Army Sergeant, played by Dennis Price, a British Land Girl, played by Sheila Sim, and a US Army Sergeant, played by real life American Sergeant, John Sweet.

On their way to the village the girl has glue poured over her head by a hidden assailant, who then runs away. The three pursue the assailant but lose him in the dark of the blackout. It turns out this has been a regular occurrence in the village. The bulk of the film consists of a silly crime mystery, with the three characters amassing clues in order to expose the “glue-man” for his misdeeds.

The film’s notable for its use of a match cut in the early part of the film, which inspired Stanley Kubrick’s famous cut in his 1968 masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey—the one where the bone thrown into the air turns into a space station. The film opens with a narrator quoting the opening lines of Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales, from which it takes its title. We see the pilgrims wending their way along the old Pilgrim’s Way from Winchester to Canterbury, dressed in their medieval gear. There’s jolly music, the tinkling of bells, and much sport. Someone is pushed off their horse. One of the characters carries a hawk on his wrist. At a certain point we see a pigeon rise in the air, then a shot of the hawk with his hood being removed. The hawk is let fly into the air. We see the pilgrim looking upward, followed by a shot of the hawk against the brightness of the sky.

At this point the hawk turns into a fighter plane, and the pilgrim becomes a World War II British soldier, wearing a helmet, with his gun, bayonet fixed, over his shoulder. The implication is clear. There is an indelible line from the days of Chaucer to today, which this film sets out to demonstrate.

The first thing to note at this point is that the route of the pilgrim’s journey as it is portrayed in the film is entirely fictitious. Although there’s an ancient trackway, known as the Pilgrim’s Way, leading along the North Downs from Winchester to Canterbury, this isn’t the route that the actual pilgrims took. Chaucer makes this clear, as his pilgrims meet at the Tabard Inn in Southwark, London, and make their way down Watling Street, along what is now the A2.

The name “The Pilgrim’s Way” is a 19th-century invention. Although it applies to a prehistoric trackway, which led from the Kent coast to the ancient ceremonial sites of Stonehenge and Avebury, it was probably not much used by medieval pilgrims. The route still exists, hugging the south face of the North Downs escarpment, which divides Kent into two, with the “High Weald” on one side, and the “Low Weald” on the other. The Pilgrim’s Way itself lies comfortably between the two, keeping a level course along the chalk escarpment, avoiding both the marshy lands in the valleys below, and the uneven uplands above. It’s the natural route from the East to the West, from the coast to the sacred sites of Britain, and is marked by several prehistoric remains. Known as the Medway Megaliths, these include the Coldrum Stones and Kit’s Coty House, two well-preserved long barrows overlooking the Medway Valley.

In a way this justifies the film’s use of the Pilgrim’s Way as its preferred route, as its theme is about the way the past is always present in this part of the world. There’s more than one past hidden in the tale. A prehistoric track becomes a medieval pilgrimage road, which turns into a railway line in the end, while the film itself is an historical artifact, viewed from the current vantage point.

There are a number of speeches which explore the idea of the past intruding upon the present. In one, the local magistrate and amateur historian, Thomas Colpeper (played by Eric Portman) talks about walking in the English countryside, and how this connects us to the characters in the Canterbury Tales.

“When you see the bluebells in the spring and the wild thyme, and the broom and the heather,” he says, “you’re only seeing what their eyes saw. You ford the same rivers. The same birds are singing. When you lie flat on your back and rest, and watch the clouds sailing, as I often do, you’re so close to those other people, that you can hear the thrumming of the hoofs of their horses, and the sound of the wheels on the road, and their laughter and talk, and the music of the instruments they carried. And when I turn the bend in the road, where they too saw the towers of Canterbury, I feel I’ve only to turn my head, to see them on the road behind me.”

Would that this were true. The sight of those bombed-out remains on Canterbury High Street at the end of the film, remind us of the devastation World War II wreaked upon the historic architecture of Canterbury, and by implication, how war changes our landscape. And no matter how hard we listen these days, we’re unlikely to hear all the same birds our forefathers heard. In Kent we rarely hear the cuckoo anymore, or the whistle and twitter of the swallow or the swift. These birds have almost completely disappeared from our countryside.

What would our Canterbury pilgrims make of the world we have created since their departure?

Canterbury remains a largely attractive city, with walks along the River Stour leading from the city center into the open countryside. Although it was heavily bombed during the war, there are interesting medieval buildings still in existence, and a city wall with one remaining medieval gate and a castle.

It seems strange that the Germans would’ve bothered to bomb Canterbury, as there’s no industry here. The answer to that riddle perhaps lies in its spiritual significance to the nation. The Cathedral is the seat of the Anglican church, the place where Augustine came to covert the English in the sixth century. The story goes that the vergers of the Cathedral were supplied with rackets during the war, in order to knock encroaching bombs away from the Cathedral grounds during air-raids. How English is that: playing tennis with incendiary devices?

Although some scenes in the film appear to take place in the Cathedral, this was all done by special effects, as the Cathedral was boarded up at the time, its precious stained glass windows taken down and put into storage.

The use of a real-life American sergeant to play the part of Sergeant Bob Johnson is a clear attempt to link the two nations together. The film came out in 1944 when American involvement in the European war was at its peak. There are several references to English culture obviously designed to appeal to an American audience, and the interactions between Sgt. Bob and the English schoolboys are delightfully quaint.

John Sweet later stated that “the few months I spent making the film were the most profound and influential of my life.” He gave his entire fee—$2000, a huge sum in those days—to the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

Central to the movie’s theme is the idea of pilgrimage. In the words of Colpeper, the medieval pilgrims travelled to Canterbury to "receive a blessing or to do penance." At the end of the film our three sleuths catch a train to the city, which we’re meant to interpret as a modern form of the same historic pilgrimage.

I won’t give away the end. Suffice it to say that the film concludes with soft-focus mysticism and an appeal to England’s ancient past. As a piece of propaganda it’s obviously an exercise in morale boosting. The audience is meant to look upon the towers of the Cathedral and see inspiration there. The Cathedral is glimpsed from the ornate windows of another church, the bells chiming in an ecstasy of jubilation, suggesting the end of the war. We see England’s indomitable spirit unbroken, and the link between the UK and the US reinforced.

On a deeper level, we’re reminded of the potent appeal of pilgrimage to the human spirit. The pilgrim’s journey is a metaphor for the journey of life: the destination, a place of spiritual significance. Wherever you go in the world, whatever the religion, people are inclined to undertake pilgrimages. The journey’s internal and external at the same time. It’s sacred and mundane. A pilgrimage is like a holiday but with spiritual benefits. It feeds the soul as well as the body. It feeds the heart as well as the mind.

What are we seeking exactly? The same as with the rest of our life. We’re seeking our destiny: our destination.