Everybody knows what the American Dream is supposed to represent. Teachers love to introduce the concept in social studies classes; as a rhetorical accent, politicians trot it out incessantly. The idea boils down to this: America is a land of equal opportunity where anyone can get ahead by dint of hard work and determination. While beyond a certain age most of us have disabused ourselves of this myth, we’re usually inclined to perpetuate it anyway—passing it down to our children and looking to it as a beacon of hope in lives which, more often than not, aren’t what we’d expected or hoped they would be.

HBO’s The Wire was a masterful, five-season TV series about a great many things—crime, drugs, institutional dishonesty, dying media, bullshit politics—but it also took a petri-dish approach to character. Viewers can and do debate, even now, about the program’s most memorable protagonists and antagonists.

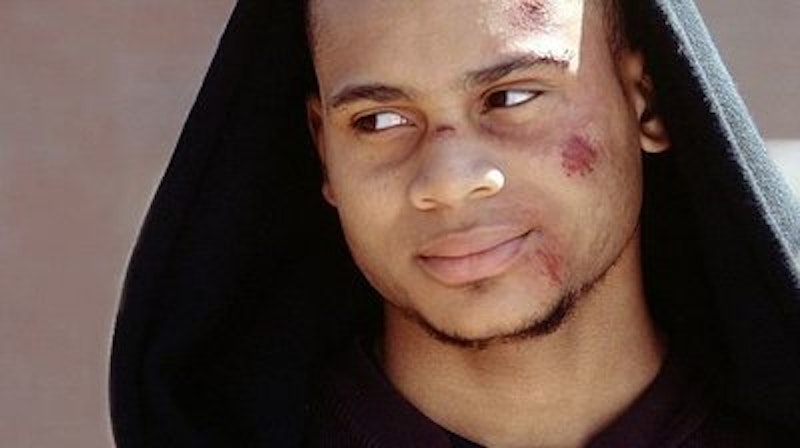

For me, Bodie Broadus (J.D. Williams) stands out in a few interesting ways. There are aspects of personality, of course: the street-ready hardness, the brash, never-say-die attitude, the rare, concealed flashes of sensitivity. But Bodie is most significant as series creator David Simon’s stealth avatar through the rotted vagaries of the late capitalist structure, an underworld example of how the American Dream can fail even the most battle-ready of soldiers. We don’t witness the entire character’s life. To get comic book about it, had there been a The Wire Season 0, we might’ve gotten to know Bodie as a young hopper, a lookout whose brother was still alive. (His parents are a mystery.)

The show presents him to us, in Season 1, as a “crew chief”—tantamount to something just below middle management. In fact, it may be helpful to think about Bodie less in terms of narcotic-sales chain of command, and more in terms of the modern office environment; viewed through this lens, the parallels between The Wire and your own live become starker.

Season One: We meet Bodie as one of two supervisors, Poot’s the other; D’Angelo serves as their chief. (A key scene, from Season 1, where D’Angelo teaches Bodie the basics of chess, presages the fates of most characters and provides the audience with a blueprint for what the show is about.) D’Angelo demonstrates loyalty to his superiors and underlings, showing deference to the former and imparting wisdom and guidance to the latter. Bodie proves himself reliable by fending off regulators and aggressively defending the business, sometimes at great risk to his personal freedom and well-being. The CFO, subverting chain of command, subtly entrusts an unpleasant bit of immoral corporate skullduggery to Bodie and Poot; when D’Angelo departs for “greener pastures,” Bodie and Poot collectively inherit the chief role. Oh, indeed: Bodie has worked hard, stayed true, and earned this fucking promotion. He’s on his way up.

Season Two: With greater power comes greater responsibility for Bodie: important business travel, a seat at the table in staff meetings, a nominal say in the direction the business moves. Opportunity is knocking, and hard, though Bodie isn’t fully aware of this. Because the CEO is on an extended sabbatical, the CFO is in charge, but since the CFO is broadening his educational palette and exploring other avenues, the input of chiefs is at a premium. The downside of that is that downfalls in business lead the CFO, who is under a great deal of pressure, to lash out frequently at the chiefs. That, however, is the cost of greater power—which also means, sometimes, that one must take part in naked, violent power grabs.

Season Three: Two major things happen at once: the company is forced to relocate and a re-org shakes things up. Then, suddenly, supply difficulties force the company to partner with a competitor. In the midst of chaos—Bodie, who is frequently responsible for coordinating supply and overseeing distribution at this point—stands tall and is mostly unshaken. Continuing to side-step persistent regulators, Bodie made a point of extending a welcoming hand to a key returning resource, helping that person feel at home within the company culture again after a lengthy retirement. Then, one huge thing happens: regulators shut the company down as it was preparing to pursue the hostile takeover of a feared competitor. The CEO and CFO are in the wind. And just like that, all of the corporate capital Bodie has acquired is gone; he’s left wandering the edge city alone, empty briefcase dangling in hand, a man without a country.

Season Four: Following a brief stint with a subsidiary of his old company, Bodie, now a freelance chief managing a team, has tumbled several rungs back down the corporate ladder—he’s working for the competition. The competition promotes a frostier, more disparaging corporate culture, one where profit sharing is little more than a pipedream. Stationed in a poor business district, Bodie’s prospects for advancement are dim. One of the supervisors who reports to him, Lex, allows emotion to get the better of him, sabotages another department, and is dispatched forthwith; his employees are young, inexperienced, and uncommitted. Bodie takes on a temp (Michael) after one of his freelancers (Namond) is unable to work consistently. When another of his supervisors is fired, Bodie experiences a meltdown, and is forced to take a leave of absence. The stress and uncertainty of circumstances is getting to him; he’s not a young man anymore, and doesn’t have as many options as he once did. Certainly there are bills to pay, and less money to pay them. Returning from leave, a regulator asks him to lunch, and as Bodie makes the mistake of accepting, an executive observes this. At mid-day, in a humiliating display of arrogance, the company has Michael—the onetime temp who has been promoted associate security consultant—fire Bodie within view and earshot of his employees. Just like that, his career is over.