In interviews to promote the sometimes glacial First Reformed, director Paul Schrader has spoken of his invocation of “slow cinema.” Among Westworld the series’ virtues is a willingness to let scenes run several beats too long. (See also Martin Scorsese's slept-on epic Silence; see most episodes of 60 Minutes; see the last scene featuring Laura Flynn Boyle and Philip Seymour Hoffman in Happiness.) On an episode of WTF with Marc Maron, the late actor and comedian Garry Shandling extolled and demonstrated the power of a pause. Patience. Patience is magic, and for the most part, you, and I, and everyone else are routinely short on patience—ain’t nobody got time for that.

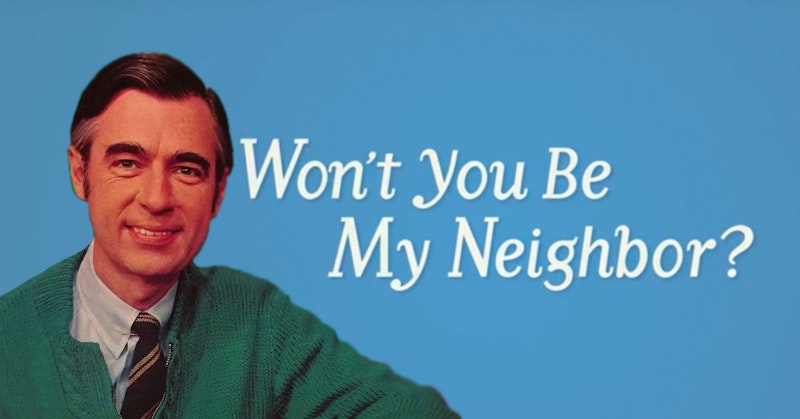

In the mid-1970s, the late Fred Rogers temporarily put Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood on ice. After a decade spent communing with children it was time, he felt, to engage with their parents. Old Friends, New Friends debuted on PBS in 1978. In Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, his new documentary about Rogers’ career, director Morgan Neville looks in on Rogers and a guest, the pianist Lorin Hollander. They are flanking a piano. Rogers is attentive, dialed in, solicitous but not to the degree with which we’ve become familiar. Unhurriedly, he asks Hollander something along the lines of “Does it ever feel like when you play this piano, you’re in another world?” Hollander’s answer—it’s a lovely one—is similarly protracted, moving at the speed of a train of thought coalescing in the present moment. It’s an exchange at once soothing, narcotic, and eternal.

Neville, a modern filmmaker, knows better than to mimic his subject’s pace. But he knows well enough to co-opt his subject’s rhythms, to give the audience a taste of what was. What was is dream-like in fidelity, in grain, in scale, in tempo: the camera dollying slowly over a marvelously makeshift model city, that signature red trolley disappearing into a tunnel, the regulars harmonizing with host-piloted puppets, the host himself, slowly shrugging into and out of colorful sweaters or performing an unguarded song about optimism that he wrote himself for every single child watching at home. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? paints a broader societal picture, to provide surrounding context, to encapsulate the Rogers origins story—the seminary school term, the emergence of television, the realization that television already kinda sucked and that he could likely effectively minister through it, the lifelong Republicanism—and to demonstrate how and why the man became an important cultural figure, a significant if imperfect voice in times of trouble.

I only teared up four times during Won’t You Be My Neighbor?, and fought off sobs twice. But Neville takes care to weave in humor to help leaven the sense of sadness here; Rogers’ children, cast, crew, and friends are hardly precious about the man. And they elicit enough laughter from audiences that we’re able to temporarily forget that our fraught, fractured modern world lacks anyone quite like him—a unifying, non-political moral figure we know from the idiot box who has our best interests at heart, who calmly cracked the code necessary to gently introduce children to life’s darknesses, who purposefully and repeatedly washed his feet alongside an African-American’s, who spoke slowly and deliberately because he knew that the things he needed to say really, really mattered.