The 1988 film Hobgoblins explores the rocky relationship shared by reality and fantasy. It’s also one of the shoddiest films ever to rip off Gremlins. Joe Dante’s controversial 1983 chiller about ultra-violent micro-monsters spawned many imitators. Hobgoblins tried to put a new spin on horror’s cuddly killers-sub-genre by turning it into garnish for bigger themes of existentialism and psychological horror. While these touches never hide the film’s lowbrow subplots, Hobgoblins’ attempts to subvert its own formulaic goofiness make it an essential work.

Hollywood High graduate Rick Sloane was the young weirdo responsible for concocting Hobgoblins. Its marriage of the complex and simple, the cheesy and profound wasn’t new for this young schlockmeister. The root of the film’s thematic clash lay in Sloane’s first major creation, a horror fandom event called “The Third Annual Transylvanian Convention.” This event became famous for premiering Shock Treatment, the 1981 sequel to The Rocky Horror Picture Show. The convention was produced and booked by Sloane and covered in a syndicated TV special called Rocky Horror Treatment. Clips from that special later made it on to NBC’s Real People, one of the first American reality TV hits. Sloane carefully crafted an environment where people could gather together and become one with beloved characters via the creative cosplay, fashion design, and other performative elements inspired by the Rocky Horror series.

Rocky Horror Treatment and Real People’s “Transylvanian Con” coverage put the spotlight on an immersive fandom strain that was just beginning to become commonplace. The two works must’ve inspired a litany of questions for middle-of-the-road/commercial TV audiences of the early-1980s. Were these insane people lost in a fantasy? Or, like rock festivals, The Super Bowl, organized religion, and electoral politics, was it all just another socialized ritual of mass performance? The connection of reality and fantasy was also an element in Sloane’s first celluloid offering, Blood Theater. In that 1984 film a decrepit movie palace becomes possessed by violence as a new staff attempt to launch a grand re-opening for the architectural relic. By depicting a cinema as a catalyst for brutality, Sloane implies that immersive entertainment’s effect on consciousness can often be just as volatile as insanity, social unrest, and other sources of physical and mental destruction.

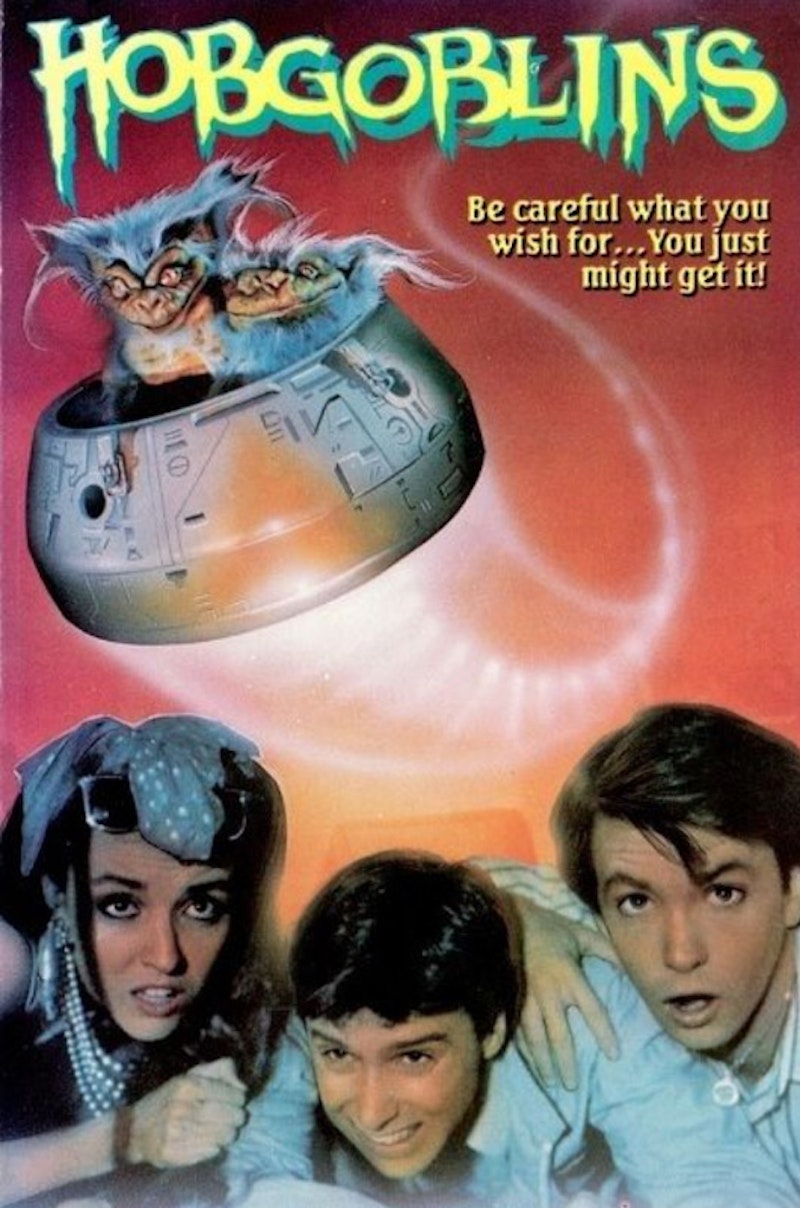

Just like Blood Theater and the “Transylvania Con,” cinema is at the center of Hobgoblins’ action. Cute/Teddy Bear-sized aliens (some of the most hilariously inanimate puppets ever) arrive on Earth and land on the grounds of a movie studio circa the 1940s where they begin killing and eating humans. Instead of just immobilizing the humans, before killing them they alter the consciousness of their victims by telepathically making dreams “come true” in vivid fantasies that annihilate all inhibition. A security guard at the movie studio traps the murderous critters (which he dubs “hobgoblins”) in a heavily-fortified film vault. Decades later a novice studio guard (Tom Bartlett as Kevin) accidentally sets them free. From there the monsters tear through suburbia leaving a tangled mess of outlandish delusions and dead bodies.

The main human characters are five teensploitation stereotypes, a group of friends who make The Scooby Gang seem like the cast of M.A.S.H. There’s Kelly Palmer as Daphne, the proudly promiscuous blonde hottie; Paige Sullivan as Kevin’s girlfriend, the meek prude Amy; Billy Frank as Nick, a lonely nerd obsessed with phone sex lines; Steven Boggs as Kyle, an alpha male soldier. Finally there’s Bartlett’s character Kevin, an insecure everyman. Riddled with guilt after unleashing the alien chaos, Kevin wants to make a positive mark on the world and impress Amy by becoming the bravest, hobgoblin-killing security guard ever. Under the dangerous spell of alien fantasy, Kyle becomes a valiant war hero, Nick mounts an effortless sexual conquest of phone sex star Fantazia (Tamara Clatterbuck), and Amy blossoms into a passionate striptease queen. Kevin and Daphne are never ensnared by alien fantasy traps. This is a sex positive nod to Daphne’s active love life, a living dream that came true as a result of sheer positive willpower. Always laughing at everyone else’s hang-ups, she’s never lost in any dream world other than the one created by recollections of her own wild sexual history.

Kevin’s dream is what keeps him grounded and protected against the hobgoblin-induced fantasies. He fights the aliens’ illusory threat by focusing on an idealized heroism that’ll strengthen his relationship with Amy and impress his aged security guard boss (the same guard who locked the hobgoblins away decades earlier).

Like New Age philosophy and dream interpretation, the hobgoblins are fuzzy weird things who originated in an out-of-the-way place beyond easy description. Sloane’s Hobgoblins is awesome because it inspires viewers to think when considering the source of dreams, goals, and mysterious phenomena. Can a mundane ambition overpower the forces of delusion? Can sexual promiscuity alone bring about a stress-free life? Are the blurry moments just before death all that can turn a dream into a reality?