As bad as Magnolia is, it holds together. Through the frogs and the singalong (the best parts of the movie, besides Tom Cruise’s performance), the movie is bad: over-earnest, saccharine, adolescent, treacly, and lacking in every way that Paul Thomas Anderson’s previous film, Boogie Nights, wasn’t. Anderson’s 1997 breakthrough may have been advertised and written about as a cross between Robert Altman’s Short Cuts and Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas, but Boogie Nights is far more precise than any Altman film, and it’s so much more fun than any of Scorsese’s rise and fall epics. Both Boogie Nights and Magnolia are three hours long, give or take, and they feel tight as a drum.

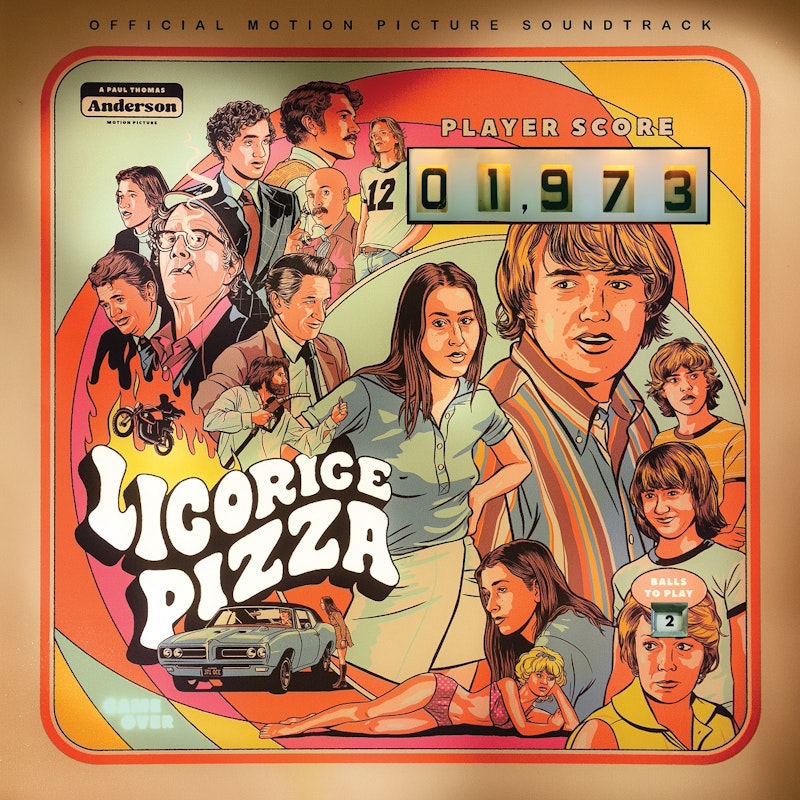

Since Punch-Drunk Love in 2002, every movie Anderson has made has felt bloated and empty, films full of holes and a lack of exposition that rarely feels purposeful or effective, rather revealing a shaggy script and a shoot that produced far more footage than could fit in a feature film. Anderson, like peer Quentin Tarantino, views himself as a writer as much as a filmmaker, and his films suffer for it. Licorice Pizza, his latest, is the best movie he’s made since The Master, but more than ever you can see the seams: this is a movie of episodes with no connection. There’s no Magnolia or Short Cuts criss-crossing, or even the slender thread that keeps Richard Linklater’s Dazed and Confused going. Ditto for Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, another Los Angeles period piece hangout movie set around the same time.

Licorice Pizza never criss-crosses or loops around, it goes in a straight line: here’s the Sean Penn section, here’s the Bradley Cooper section, here’s the Benny Safdie section. Anderson’s disdain for traditional exposition, almost always a good sign elsewhere but usually a problem for him, works here: the opening shot is Gary Valentine (Cooper Hoffman) and half a dozen other boys in their high school bathroom combing their hair on Picture Day. Suddenly you hear a fuse, someone yell “CHERRY BOMB!”, and a toilet in the background erupts with water. They all rush out with smiles on their faces.

Cue the title. Gary meets Alana (Alana Haim) in the next scene, rushing up to her in line with all the confidence and charm his father’s characters always lacked in Anderson’s movies. Gary Valentine is a far cry from the sad, pathetic slob Philip Seymour Hoffman played in Boogie Nights; or the saintly but sniveling nurse to Jason Robards in Magnolia; or the boneheaded mattress salesman gangster in Punch-Drunk Love; or, even, finally, Lancaster Dodd in The Master, outwardly confident and successful but a fraud and a spiteful dilettante at that. Anderson’s usual dives into American male plumbing—upstairs and downstairs—are refreshingly absent from the thoroughly joyful Licorice Pizza.

Even so, this could’ve been his masterpiece. Instead, it’s another stoned collection of scenes and set pieces that don’t amount to much or say anything cohesive. No statement or grand experiment is necessary, but this is a movie that suggests so much more—as always, look at how much unused footage is in the trailer. I’m not asking for a mini-series or a Shoah-length director’s cut, but Anderson’s approach to “masterful filmmaking” is holding him back. There’s enough in this movie to make it an instant classic—mostly Hoffman and Haim, but what they’re given to do in just 130 minutes doesn’t feel enough, and not in a satisfying way. Anderson writes his scripts in prose form in Microsoft Word; a fine method, but misleading when it comes to typing it up as a screenplay. You inevitably end up with scripts that will make movies over three hours long.

It’s a really great movie, but it’s not a masterpiece. That may sound bratty, but Anderson’s one of the few active American filmmakers who really could make a masterpiece. Besides the structure, Jonny Greenwood and he need to take a break from each other. Since 2007, Greenwood has done the music for every Anderson movie, with diminishing results each time. From the astonishing atonal score for There Will Be Blood to the bloodless glissandos of Phantom Thread, Greenwood takes a backseat here essentially as music editor for pop songs and themes of the early-1970s. You’ll hear Ernie Anderson, the dearly departed elder, on the TV announcing some sitcom, you’ll hear the overused “Life on Mars?”, you’ll hear commercials wrapped in static coming from car windows and bedside tables. But there isn’t a single memorable musical moment in the movie, unlike Tarantino, whose movies frequently have dozens. Anderson is usually good with music as well, but the score to Licorice Pizza wafts by without offense like pot smoke, like all of the movies he’s made in the last decade.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith