Perhaps it’s only a sign of good material that I was called a bitch and physically threatened while watching For Colored Girls, the newest Tyler Perry flick. Yes, in the midst of watching a film about violence perpetuated against black women, I was on the receiving end of a very personal verbal assault. In the backdrop of the moving on-screen characters was a baby girl in the row behind me, intermittently giggling, crying, talking, and patting a friend sitting next to me on the forehead. While adorable, she was distracting. And as I had ignored her father’s earlier commentary on the “faggots” in the film, I felt like I was well within my right to let the management know about the frequent interruptions. I should have anticipated the threats of physical violence and name-calling that my action would provoke.

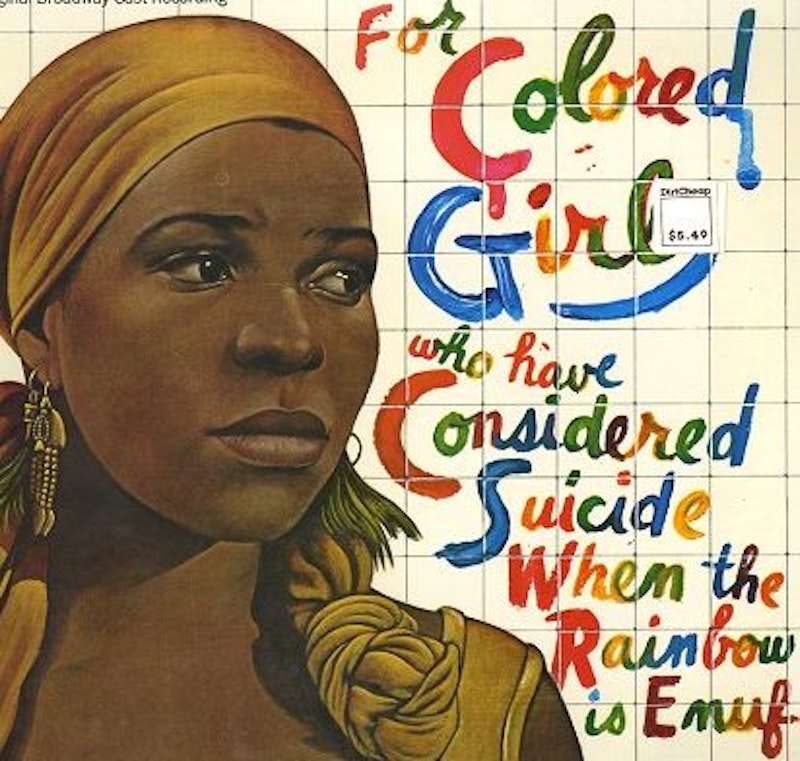

Now, I offer this tale of the theater experience of seeing For Colored Girls because it seemed to justly supplement the material on screen. The play-adapted film is largely about giving black women the opportunity to tell stories that we so often hide, lending faces and bodies to the insecurities, fears, and traumas that are rarely voiced. Perry’s version of Ntozake Shange’s choreopoem is both impressive and over-the-top. Perry’s cast members, including favorites such as Phylicia Rashad, Kimberly Elise, Loretta Devine and Whoopi Goldberg, make the screen sing with their presence. One surprise is the performance of Tessa Thompson, who lends realism to her occasionally awkward lines as a troubled but ambitious teenager.

Despite the cast’s best attempts, the persistent presence of Perry’s inner demons and flawed directing find themselves spoiling yet another cinematic venture. As if the original script of For Colored Girls is not fraught with enough of its own heartache and troubles, the director reaches into his familiar bag of tricks to add in narratives about a “Down Low” cheating gay husband and an incestuous grandfather aided by a neglectful mother. This forces unnecessary melodrama into a script already filled with angry, beaten down, cold, abused, and embattled characters. Mix that in with one character’s HIV contraction and Perry’s story moves past the bounds of stereotype and becomes just plain offensive. I’ll leave out most of my other commentary on his use of cheap film devices (please God, stop with the close up and opera-singing), but will say that his heinous borrowing from movies like The Godfather and The Devil Wears Prada just reinforces his lack of originality and makes his weaknesses as a director more clear.

There are moments when the film shines. The first is that Perry was able to make the film at all. Most of us theater buffs and lovers of Shange’s work were unable to imagine any way that one could convert the series of unrelated, poetic monologues into a concrete set of movie characters. Perry’s work to develop the characters frequently pays off, weaving the poems into the characters’ lines with surprising ease. The women perform loud and quiet, strength and weakness, coldness and vulnerability, sexuality and love, all through a wide range of hair and body types, ages, and skin tones. This diversity in representation, perhaps, is the film’s greatest strength. Perry’s film manages to defy the simple asexualized mammy/ hypersexualized jezebel archetypes that so often restrict black female performers.

After the movie was over, I walked out of the theater into a confrontation with the couple, baby and all. Fortunately, no fists were swung and I did my best to defuse the situation. But, I was in large part surprised—one would think that this film would open up conversations about city violence, that it had the potential to make people think. At the very least, I did not envision a black man and woman, holding their female daughter, physically attacking someone over their inability to finish For Colored Girls in an urban setting.

Maybe that was Perry’s biggest failure. Don’t get me wrong; I don’t expect his work to bring about world harmony. But with greater artistry, beauty, and talent, I think the material of For Colored Girls could have offered more than easy cracks at the expense of gay men and shocking, gratuitous violence. While it entertains, some of the work's power gets lost. In terms of the scarcity of such incredible performance opportunities for black women, I would not hesitate to recommend this film. But, in the end, Perry’s rendition doesn’t ask much of his audience.