Josef von Sternberg’s cinematic vision was focused on aesthetics rather than social commentary. Although the social mores and class structure have been part of his oeuvre (most notably in his 1930 The Blue Angel), von Sternberg was not driven politically or ideologically. He was more interested in the ways interior lives of the characters could be illuminated on the screen.

One can understand the angry reaction of Theodore Dreiser—the author of the 1925 novel, An American Tragedy, which was adapted by von Sternberg and financed by Paramount Pictures. Dreiser, a committed, card-carrying Communist, turned literary symbolism into socialist ideology, and expected the adaptation on his novel to be true to his creation. The interactions between the classes and evil of capitalism as Dreiser saw it was far more important than aesthetic visions of a difficult, expressionistic film director.

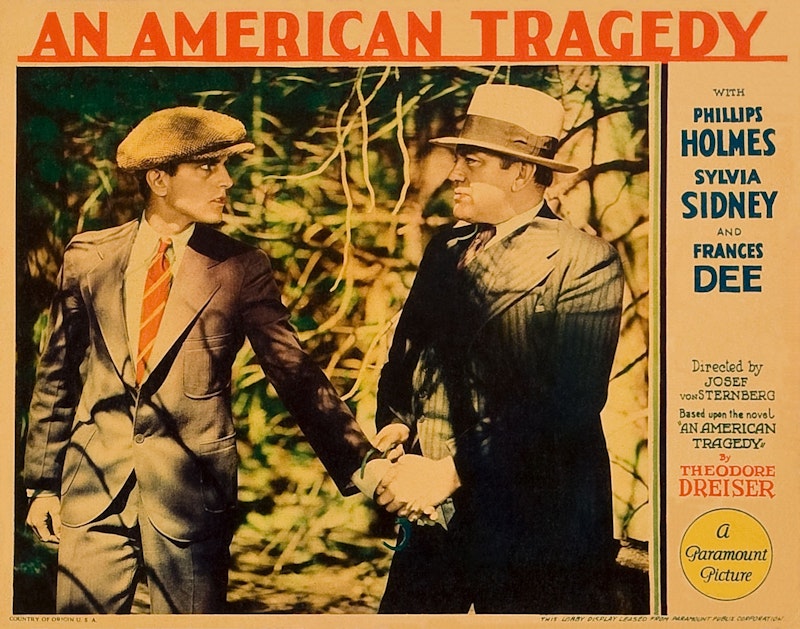

Despite this, von Sternberg’s 1931 An American Tragedy stands out as another unique vision of this painterly director. Much like Dreiser’s novel, the film tells a story of Clyde Griffiths, a poor young man seeking a better life in America. His parents run a Christian mission but he wants nothing to do with it. After taking many menial jobs, and trying to avoid culpability of a hit-and-run accident that his friend caused, Clyde leaves his home, seeking better fortune.

He takes a job at the factory of his wealthy uncle, who gives him a supervisory position, in which Clyde is in charge of young women workers. There, he meets Roberta Alden, and it appears that he falls in love with her. She’s smitten by him and hopes that they’ll get married. But there’s something unsettling about Clyde. The more Roberta trusts him, the more the audience questions his motives.

Clyde’s an opportunist, and once he enters the high society and meets Sondra Finchley he drastically changes his attitude toward Roberta. He avoids her and things get even more complicated when Roberta tells Clyde that she’s pregnant. An implied talk of abortion is present but neither is the pregnancy nor abortion ever mentioned by name. They decide to not see each other for a little while. Roberta’s assured that Clyde will remain faithful but he abandons her for Sondra.

As he’s moving up in society based purely on his association with Sondra, Clyde realizes that Roberta will only get in the way of his success. Luring her into the beautiful woods and the lake, Clyde plans to murder her. Roberta knows that something’s wrong. Clyde’s face turns icy, and as she’s trying to repeatedly ask him what’s wrong, Clyde becomes aggressive and the boat capsizes. Roberta’s unable to swim and although Clyde has many opportunities to save her, he chooses to swim to the shore. Unfortunately for Clyde, he’s caught and endures the trial. He makes no sense, and continuously gives contradictory and confusing testimony. He plays an innocent, morally corrupt coward, which is the approach the defense has taken. But Clyde can’t escape the jury’s verdict of guilty.

Von Sternberg chooses to focus on the symbolism of water. Drowning is obviously one of the main themes of the film, and throughout the film, we see the intertitles (something von Sternberg continuously used) that are disappearing into the shimmering and brilliant river or creek (we see a similar approach to filming water in his 1933 Blonde Venus).

As always, von Sternberg is concerned with reality and illusion of existence. Clyde and Roberta are living in separate worlds, making demands on each other. Both are tired of their lives and social standing, and as a result, they oscillate between what is and what could be. But their paths are divergent. Clyde appears to be more of an opportunist who’s willing to shape shift in order to get ahead. It’s not clear where his fantasy of an American life is going or where it will end. One wonders whether he would’ve left Sondra Finchley for another socialite once he got tired of her.

The characters are far from authentic and almost everyone has some moral corruption. Without a doubt, Dreiser would say that it’s capitalism that has made them into morally bankrupt people, and there is some indication of this at the end. As Clyde sits in his jail cell, awaiting to be executed, the only person who comes to see him is his mother, who, in some way, excuses Clyde’s actions. She blames herself for not giving him a better life, and tells him that he never should’ve been exposed to so much evil.

Is Clyde evil? Von Sternberg’s aesthetic subtleties transcend any social commentary at the service of Communism that Dreiser has done. For most of the film, Clyde is hapless, almost a fool that falls into bad situations. He’s like a bad child who stole a pack of gum something and then yells, “I didn’t do it, mister! I swear on my life!” But there’s more to the seeming stupidity of Clyde’s personality.

There are two mirroring scenes that von Sternberg brilliantly juxtaposes. In the earlier part of the film, Roberta passes a note to Clyde in the factory. He hides behind the staircase and reads it. In the note, Roberta implores him to see her. In one brief moment, Clyde smiles at her, and in her naïveté, Roberta accepts it as a sign of love. But Clyde’s stare is icy. It’s a smile fraught with darkness and evil intentions despite the dullness of his personality.

Mirroring this is the scene that comes at the film’s end. His mother, sitting in the courthouse, looks at her son, seeking the truth whether Clyde was capable of murder. Tears stream down her face in what begins as an acceptance that Clyde’s innocent. But as Clyde looks at his mother, he offers her nothing more than the icy smile that only leads to a mother’s confusion and absolute sadness.

It’s thankful that von Sternberg chose to reject social commentary because his aesthetic vision is far more powerful than Dreiser being a shill for Communism. He shows what lies beneath the dark lake of one’s soul, as well as “the banality of evil,” to use Hannah Arendt’s phrase. The point of the film is not whether Clyde’s evil deeds are the result of an unjust society, but what kind of evil he’s exhibiting. He’s a dull young man, and somewhat confused. This may induce compassion because he’s not a stereotypical villain but the line between virtue and vice can be thin, which makes us question the very meaning of evil. Clyde Griffiths may not be a psychopath, and he may be dull and even dim-witted. Ultimately, however, what makes his actions evil is the indifference toward human life.