There’s no filmmaker in history less suited to provocative political screeds than Michelangelo Antonioni. Cinema’s greatest chronicler of domestic depression may have had passion and drive in matters of American civil discourse, but any message in Zabriskie Point is drowned out by his natural instincts as a stylist. The man wants to talk about consumerism, inequality, environmentalism, the rich, student protests and the Black Panther party, but he just can’t help himself... when an arthouse director sees a wide-open desert, a sea of billboards, a house exploding, they need to make it beautiful. He needs us to see the style, and allow it to drive our experience.

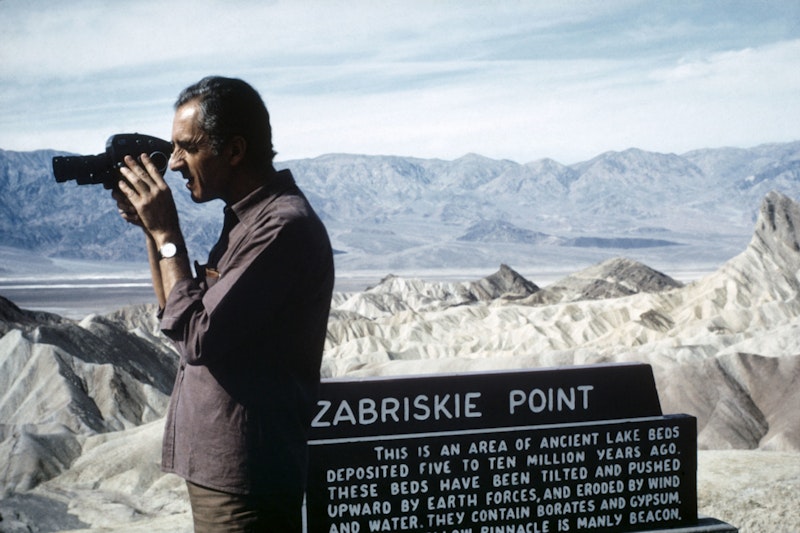

The historical standing of the Italian director’s first Hollywood-backed production is odd. It received an avalanche of terrible reviews at release, but this is one of the most beautiful movies ever made, maybe cinema’s definitive visual portrait of the American desert (aside from Paris, Texas). The framing of its first act (based in Los Angeles) is gorgeous, the frame cutting up ads and using massive buildings and walls of windows to show its characters swallowed by their surroundings. The man who so beautifully captured the emptiness and beauty of Rome, Milan, and Turin, seamlessly transitions his gaze to the streets of Southern California, making the palm trees and the traffic just as striking and foreboding as their Italian counterparts.

The opening scene takes place at a student meeting of mostly white students led by two black students about civil rights protests and “what they can do to help.” The scene realistically devolves into an argument: the white students increasingly agitated at the black leaders’ hesitance and rejection of their desire to contribute to the cause of civil rights. The way this scene frames these students is slippery and weird; it’s not immediately clear whether Antonioni sympathizes with the white frustration or simply means to capture the internal turmoil of liberal inaction. Either way, it ends with Mark (Mark Frechette), the soon-to-be outlaw hero, storming out of the discussion.

This leads to a series of circumstances where the main character maintains one foot in and out of his own story. He misses a student protest that ends in mass arrest, only to be arrested himself once he comes to bail out a friend (in one of the movie’s more juvenile and sincere moments, he tells the police he identifies as “Carl Marx,” a name that no member of the LAPD has apparently ever heard of). He makes sure to attend another protest, with a gun, only to have someone else beat him to the punch when an officer is shot. Even though he’s completely innocent, he flees, steals an airplane, and flies out to the barren national parks to the east of L.A.

While this is happening, the movie occasionally cuts to the mundane adventures of Daria (Daria Halprin), a young woman who works for Lee (Rod Taylor), a real estate developer readying the opening of a large development in Death Valley called Sunny Dunes (in one of the blunter moments in the film, the TV spot for this neighborhood does not star actors, but well-dressed mannequins). She drives out to the desert, claiming at first that she’s looking for a man who works with “emotionally disturbed” children, before continuing to drive on further, with less purpose as the mile count goes up. While stopping to water her radiator, Mark sees her from the air, and gets her attention in an insane way: he flies his plane closer and closer to her car, like a daredevil version of automotive flirting.

Once they finally meet, the movie turns into a quasi-lovers-on-the-run narrative. Contrary to the hopes of the producers, and maybe Antonioni, all of whom probably wanted this story to feel urgent and modern, everything from here on out becomes shockingly old-fashioned, a story about first-look romance between two people from different backgrounds that climaxes before turning tragic. Most other versions of this story don’t chronicle the peak of the romance with a gauzy orgy sequence, where the central couple make love amidst a spread of other couples doing the same, the reality of the story shattering for a moment into rapidly changing shots: disorienting close-ups, match cuts, so much dust, and a couple of beautiful wide shots of the landscape, peppered with young couples in embrace. But that’s when the real appeal of Antonioni’s work reveals itself: what must’ve seemed pretentious and outrageous at the time comes across as dreamy and gutsy now, as pure and sincere an expression of joy as any sequence of its decade,

None of this is meant to last. Mark’s journey of uncommitted free fall ends bittersweetly, as he chooses the most honorable path while being punished for it. The real comment is the very end, where a dazed, emotionally shellshocked Daria finally ends up where she was going all along: a house, carved into a desert rock, a mirage of modernity in the cliffs. Lee is there, and so are other unnamed women. She’s treated as an afterthought to the meeting being held, which is explaining further development outside of Sunny Dunes, every shot seemingly facing a window, emphasizing the vastness of the landscape. Daria, numb to everything, exits, drives away, stops, then looks back. What follows is the most audacious moment of Antonioni’s career: as a Pink Floyd track fades in, then starts to wail, she imagines the house exploding. Not once; the moment repeats, non-stop, from every angle possible. We see the walls, the roof, the rooms, the bookshelves, the lamps, the windows and the pool go up in smoke. As the projection goes into slow-motion, what started as a consumerist assault becomes a reality time-warp, a fireworks factory of music and images that’s as awesome as it is unsubtle. Then, everything stops. Daria watches, and drives away.

If there’s one political shade that’s timeless, it’s that ending moment. Daria only destroys the house in her mind, and for those caught up in the machine, walking away is as much a true act of defiance as any tear-gassing or protest. But what makes Zabriskie Point a wonder is its artfulness. It’s a movie obsessed with images, both as agit-prop and portraiture, with the latter usually winning out. The work’s earnest, rooted-in-the-moment attempts to chronicle and take down the capitalist framework that destroys the environment, and continues cycles of oppression, come across as quaint, completely missing any mediating perspective, its characters blank slates. As a piece of political art, it’s a curio. As a piece of aesthetic filmmaking, it’s eternal, a hodgepodge of stunning framing, impeccable mood, and existential malaise.