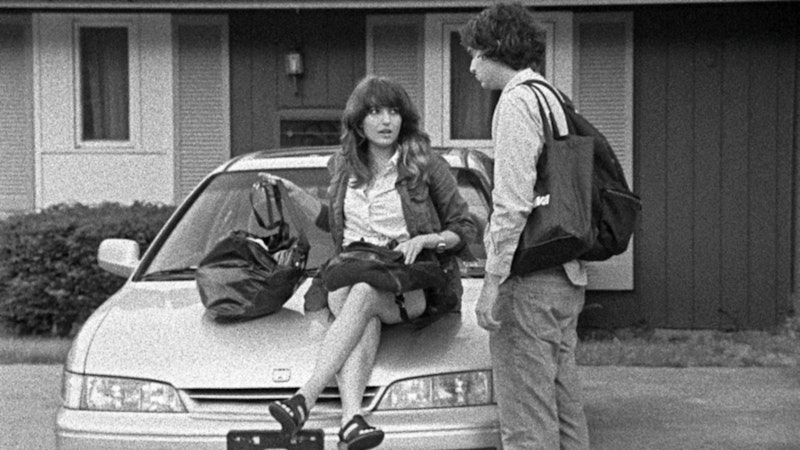

In the penultimate moments of The Color Wheel, the story one character tells another begins as an earnest projection—a potentiality, starring the listener—but ends as a co-starring fable. What happens next forces the viewer to effectively revisit and reevaluate every aspect of the movie thus far. Director Alex Ross Perry’s second film subsists on a conceit thinner than its non-existent budget: college girl enlists younger brother to help her move out of dick professor/lover’s house. And you can’t miss all the money this production didn’t spend. Everything is shot in a cloudy black-and-white that threatens to become color but never quite does; restaurant scenes presented as having taken place in different cities or towns are obviously staged in one restaurant; it’s indisputable that Perry limited the no-name cast to a handful of takes. Most of the action takes place on streets or in a few interiors—probably a single interior, artfully re-purposed multiple times.

Carlen Altman, who plays JR, shares screenwriting credit with Perry, who portrays Colin, JR’s younger brother. Theirs is a bratty sibling dissonance so gleeful—foul-mouthed, mocking, wholly reductionist—that it’s as if both actors are high on the Todd Solondz anti-ideal of saying the worst, whenever possible. Colin whines arias of JR’s insufferability, and there are implications that their parents purposely exclude her from family gatherings, but The Color Wheel serves as evidence that Colin himself occupies a higher, darker misanthropic precipice. As if these two weren’t already the last pair you’d ever want to randomly run into, every other character is somehow worse: the leering clerk at the motel where they stay; JR’s cocksucker ex, gleefully deconstructing her; the successful asshole high school classmates circling like faux-cultured vultures at the party both siblings wind up at.

A tacit artificiality runs through The Color Wheel. None of it feels fully like real life; its various gags and indignities feel forced and stagy, more uncomfortable somehow than Perry intends them to seem, probably because he’s still finding his footing as a director. But this lack of surefootedness has the effect, whether intentional or not, of grounding the drama and demonstrating why Colin and JR are doomed as budding adults. Perry isn’t a natural actor, but his brusque bumbling is believable; Altman, who’s done time as a comedian, delivers most of her lines with a stinging antagonism that helps sell her as the nightmare we’re supposed to believe she is. To say more would spoil a movie that is tender and winning in ways it doesn’t seem poised to earn, until suddenly it does.