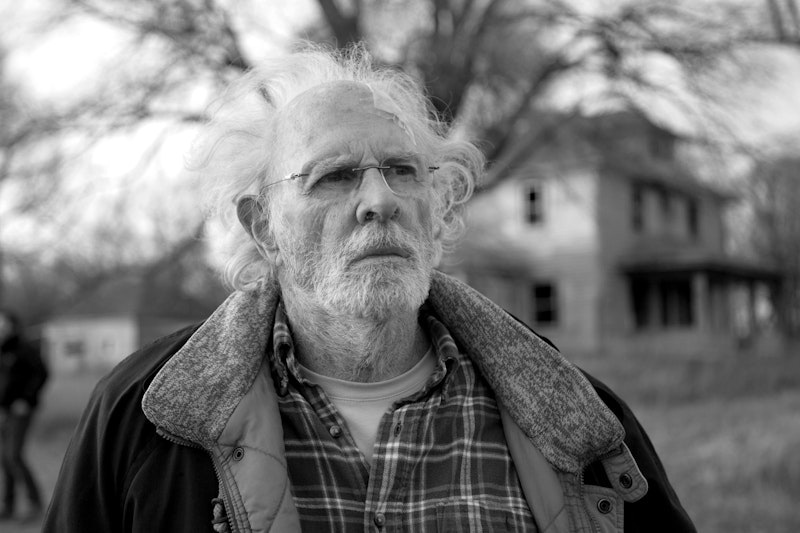

Alexander Payne’s Nebraska is a devastating, hopeless film. The beautifully simple premise: Woody Grant (Bruce Dern) is grumpy, bitter, stoic, a man of no words, near senile—a Korean War veteran with a wife (June Squibb) he should’ve never married and two sons who languished under his alcoholism, distance, inaccessibility and temper. Remarkably, they’re both successful and reasonably well-adjusted human beings—David (Will Forte), a home audio salesman and Ross (Bob Odenkirk), an anchor for the local news in Billings, Montana, where the four of them still live. With diminishing faculties and the childlike idealism and delusions that come at the end of a long, hard life, Woody gets a piece of junk mail that says he’s won a million dollars, next to a million asterisks and half a page of fine print he never sees. He’s obsessed with reaching the address listed in Nebraska and claiming his winnings, at first by walking himself, then driven by a guilty David hoping to satisfy his father’s delusions to make him happy and his mother less angry.

Kate Grant is not a beaten and mentally battered housewife—she’s clearly been the dominant partner for some time, openly admonishing and insulting her increasingly oblivious and grumpy husband in front of her sons and mixed company, with a knack for concise, acidic personal assessments (standing over the grave of a teenage acquaintance: “Whore. She was already screwing guys in the back room of the cake shop, at 15! God rest her soul but what a slut.”) Nebraska is about Midwestern men of few words, what it means to be an accomplished American man. Emotional constipation. Throughout the movie, as Woody and David, and eventually Kate and Ross, pass through dive bars, dim karaoke halls, living rooms with football and Budweiser, and endless corn, Woody insists the only reason he wants the million so bad is because he wants “a new truck... and an air compressor.” It’s not until the very end that he tells David all he wanted was to leave something behind for his sons and his wife.

The movie is shot in warm, soft black and white with appropriately stoic exterior and landscape shots, with a humble and modest eye that renders the Midwest romantic more than anything else, although this is a movie about the death of the American dream. Even though Nebraska is the first film Payne has directed without writing as well, his voice rings through, that mix of sentimentality, and an awareness and willingness to play with and embrace the absurd, a darkness towards human behavior verging on misanthropy (see Election), but always rounding back to the conclusion that individuals are basically good but institutions, traditions, nations, and habits are what make the world a hellish place. Nebraska is his most reflective and mature work yet, with a calm melancholy that sings softly from the knots in the wood paneling, the ashen skies, and the ruddy, sagging faces of small town men and women with one foot in the grave. Nebraska is a film about impotence, helplessness, feeling affectless as a “man” in 20th century terms. It offers no resolution or hope for our future as an industrial power. Instead, what we can take from Nebraska is its study of family dynamics and how emotional repression and misdirection is the root of most of our problems.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1992