Political satires by liberal and leftist filmmakers from the post-war period into the millennium grow more quaint with each passing year as American horrors mount: what’s so bad about having a job and readymade furniture? Fight Club and Office Space, both from 1999, made it seem like a soul-sucking hell, and David Foster Wallace’s last, unfinished novel The Pale King (posthumously published in 2011) was about coping with this boredom. Customer service humor—from Five Easy Pieces in 1970 to Big Daddy in 1999—was a staple for decades, now gone: who wants to bitch about intransigent drive-thru employees or pesky managers? Even if there are still insane people working everywhere like the drive-thru attendant at the Chinese restaurant in 2000’s Dude, Where’s My Car?, it’s left the lexicon, along with everything more noticeable.

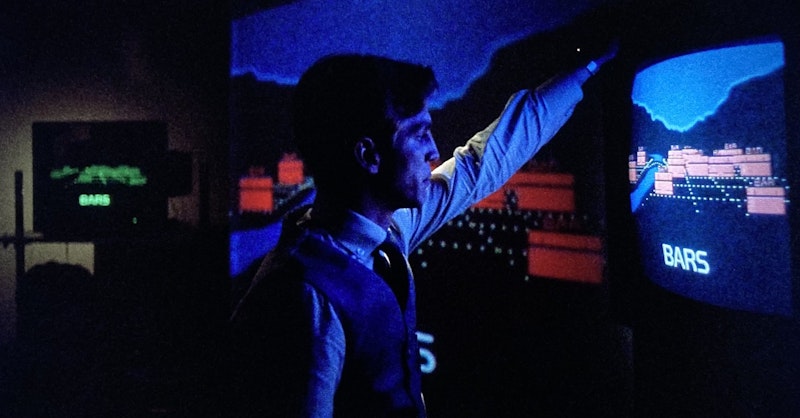

Even John Carpenter’s They Live, released the Friday before the 1988 presidential election, depicts a dystopia where capitalist aliens have colonized the Earth with the consent and complicity of the “Human Power Elite.” Like in The Matrix, the alien population is happy to give people the opportunity to earn money, eat food, have sex, and consume an endless amount of material of their choosing—all they have to do is stay asleep. It’s only when Nada (Roddy Piper) finds a revolutionary hideout filled with sunglasses that allow him to see the subliminal messages behind every advertisement and magazine and dollar bill: “OBEY,” “CONSUME,” “STAY ASLEEP,” “THIS IS YOUR GOD.” Nada and co. destroy the illusion for everyone, just like Neo in The Matrix, but what’s so bad about eating ice cream and reading magazines? The robot aliens are doing it, too.

Hal Ashby’s Being There (1979) hasn’t aged as badly as Network, from just three years earlier—Sidney Lumet did a brilliant job with Paddy Chayefsky’s unbearably purple script. Both, especially Network, castigate Americans for succumbing to TV culture while thumbing their noses at them and offering no alternative. Go outside, walk on water? In both, the principal problem is communication, and with so much information coming in constantly, it’s hard to say anything intelligible to someone else. I’m not so sure: invariably, the artists that make these kinds of media critiques are hardcore addicts, reformed or not, openly or not, including Wallace, who couldn’t own a TV for fear of recreating the device at the center of his own Infinite Jest (a book that remains potent 26 years on).

One of the reasons people responded so strongly to HBO’s Euphoria, negatively or positively, was because it was the first pop cultural product that dramatized life in America today. Andrea Arnold got there first with American Honey in 2016, but no one saw that masterpiece compared to the numbers Euphoria put up. Sam Levinson’s show is one of the only new pieces of work that depicts the doom of modern-day America in any meaningful way, and I wish it was better. Robert Eggers is a good filmmaker, but I’m disappointed that he vowed never to make a movie in a contemporary setting. Movies can’t abandon America now. Joker can’t be the most explosive pop sociopolitical satire of our time.

Dušan Makavejev’s The Coca-Cola Kid from 1985 was just reissued by Vinegar Syndrome, and while walking straight down the middle to avoid lawsuits from the surprisingly accommodating Coca-Cola corporation, it’s a movie that reminded me more of Marco Ferreri rather than Local Hero like the premise suggests: a Texas Coca-Cola man played by Eric Roberts heads to Australia to help them get into a certain market owned by an eccentric millionaire who owns the town and makes his own cola. It’s a light satire on capitalism in the vein of Robert Altman’s Buffalo Bill and the Indians, and anyone criticizing it for “not going hard enough” against Coca-Cola is missing the larger point: Makavejev spent the 1960s and 1970s making heavily censored political and sexual satires in Eastern Europe, and by the 1980s he was eager to work with Americans in a Western country. Qualm?

The Coca-Cola Kid is as dated as the above liberal critiques of globalism, but its broad characterizations recall other European auteurs sending up cowboys and “big Texas men” in a very particular and larger-than-life way that’s always more amusing than our own send-ups of ourselves. The American characters played by Italian actors in Ferreri’s Don’t Touch the White Woman! are superior to their historical counterparts in Buffalo Bill, if only because their objectivity and mild disdain can never lapse into self-pity and an obsequious need for redemption or forgiveness. American cinema is too forgiving to itself.

—Follow Nicky Smith on Twitter: @nickyotissmith