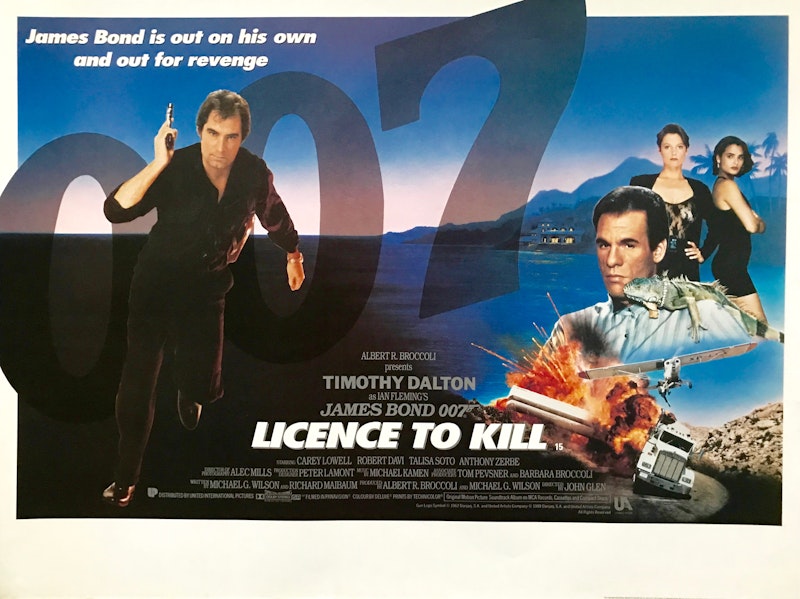

By the late-1980s the Cold War was fading away and replaced by the War On Drugs. Action stars changed their games up accordingly. From Arnold Schwarzenegger to Chuck Norris to Jackie Chan, heroes took on drug dealers and gangsters, villains audiences were happy to watch get ventilated. Timothy Dalton’s second James Bond adventure, 1989’s License to Kill, is equipped with a set of familiar characters: a sadistic Latin American cartel chef, his puppet. a hapless President-for-life, unsmiling bodyguards with sunglasses and earpieces and guns. Could this sort of crew really pose a credible threat to the world’s most elite secret agent?

They do a number on Bond’s American buddy Felix Leiter (David Hedison). After an opening sequence in which Bond and Leiter capture drug lord Franz Sanchez (Robert Davi), Sanchez bribes his way out of prison and with his lieutenant Dario (a young Benicio del Toro) feeds Leiter to a shark, maiming him, after (implicitly) raping Leiter’s new bride. Bond’s determined to take revenge, but his superiors won’t have it. When his boss tries to give him a mission in Istanbul, Bond turns it down, resigns his license to kill, and goes rogue. The pursuit of Sanchez leads him to a lovely DEA informant (Carey Lowell) and then to the Republic of Isthmus, where Sanchez is trying to swing a deal with a Japanese syndicate. Bond goes undercover into Sanchez’s operation, determined to take it down from the inside.

Dalton’s Bond never found a myth of the 1980s the way Connery’s Bond did in the 1960s, with his libertinism and mod secret bases and evil conspiracies. Roger Moore didn't have a myth of his times either, instead approaching the Bond material with an urbane irony that was a send-up of himself. But Dalton has no more irony than he does myth, presenting instead a Bond who embodies the tropes of the 1980s action film—in this movie he fights a crooked televangelist. (His Bond is also a man of the 1980s in his sex life; with AIDS a widespread if unmentioned concern, Bond no longer plays the field.) This isn’t bad, but you do feel something distinctive is missing in this movie.

The team of director John Glen and writers Richard Maibaum and Michael G. Wilson present here their fifth Bond film in a decade, and you can see steady evolution over the years from the tedium of For Your Eyes Only. Production designer Peter Lamont handled all the Glen-directed Bonds, and here creates some interesting spaces for the action, especially once the action shifts to South America. There aren’t any elaborate secret bases, but a rich hotel conveys a sense of luxury, something that works with the nature of Bond. There’s a feeling of a moneyed world, a setting separate from reality, and that’s enough to sell something of the Bond adventure fantasy.

It helps that this may be the most solid Bond film on a plot level. The villain doesn’t have an elaborate scheme to ruin; this is a pure revenge job for Bond. And, as in Dalton’s first movie, Bond performs actual espionage, infiltrating Sanchez’s gang. There’s no extraneous goofiness, and the overall tone is remarkably close to Ian Fleming’s original stories even though this is the first film not to take at least a title from Fleming.

It’s not much like previous Bond movies, though. Along with the lack of misplaced humor, there also aren’t any surreal Bond adventure elements. A couple of high-tech gadgets, but no weird cults, hidden lairs or secret satellites. It’s even more of a straightforward thriller than From Russia With Love, which at least had the criminal organization SPECTRE to liven things up.

Dalton has to be the focus of the film, and he’s a superb actor. Still, you want a bit more. Glen handles the action scenes well, Davi is good in a stereotyped part, del Toro conveys brooding menace, but there’s nothing surprising. Early Bond movies liberated the imagination by pushing the envelope of what was probable: surgically-altered doubles, hypnotic brainwashing, a woman killed by being painted gold. Without that, you wait for Dalton to stumble onto something exceptional, or do something out of the ordinary by action movie standards, and he never does. The movie’s like a cop show, one of millions of stories about a lone wolf who does things his way.

The idea of Bond as a rogue agent is good, but not a lot’s done with it. The briefing scene with M (Robert Brown) is a nice inversion from the Bond standard that triggers an action beat, but it plays out oddly—Bond refuses to turn in his gun, as though he wouldn’t be able to find another in five minutes. MI6 is never too worried about Bond slipping his chain, and Q (the ever-reliable Desmon Llewelyn) shows up later to establish that Bond isn’t all that rogue after all.

If Dalton’s Bond makes a solid action hero, he doesn’t bring something new the way the 1960s Bond films did. Oddly, although those films had a stylishness that’s distinctly of their era, Dalton’s Bond is more bound to his time because of the lack of style—he’s less of an archetype. Still, License to Kill is a perfectly sound action movie, overall arguably the best Bond of the 1980s, rivaled only by Dalton’s first film. It’s a happy coincidence that one of the most talented actors to play Bond arrived at the time the films experimented with slightly more character-oriented stories, and got material more interesting and darker than his predecessors. You can’t help but wish that he’d had more distinctive plot elements to work with. As it happened, he wouldn’t get another crack at the role.