Gauging public opinion is as hard as nailing Jell-O to a wall. It turns at breakneck speed, has zero subtlety and can simmer for decades at a time. And regardless of your political, religious or ideological views, it always feels your cause is unfairly subjugated to the sound byte: The out-of-context “gotcha!” that pigeonholes and threatens to bury a person, idea or movement. No one enjoys this; everyone participates.

Blogs and all that feel-good, "multimedia" stuff fit in nicely with the desire to sensationalize, to blow up over perceived injustices and to condemn. But there will always be the need for informed debate (insert bitter remark re: the ABC-sponsored Democratic debate). Through the muck and mire there are substantive writers and substantial commentary, but they’re often lost in the news cycle—the machine that roils the print, TV and online media. The flip side is the fact that this wide-open frontier of commentary is attracting all the readers for its instant accessibility and its limitless range of opinion.

All together, it’s a high-strung atmosphere. Case in point: In his column, “Below the Beltway” in The Washington Post Magazine, Gene Weingarten responded to the vehement vitriol he received after publishing a column (“about the overly contentious state of political punditry”) that took a few cracks at Bill O’Reilly and Rush Limbaugh. Weingarten was castigated by the infamous conservative pundits as a manic liberal from the liberal media machine spewing liberal waste.

“No criticism,” he wrote, “however nuanced, can go unanswered; it’s as though we are all on a 24/7, war room footing, where perceived attacks must be answered instantly, with maximum prejudice.”

The "war room" is the Internet and everyone has the access codes.

Go-to sites mostly reflect our political tendencies, but often those bleeding liberal or conservative wingnut destinations are part of the problem. High doses of “actually, screw you” arguments only invoke kindred responses and the cycle goes on and on. You have to wade through all that before finding a little grounded argument—but the road to enlightenment, as we know, has few working streetlights.

Newspapers are no longer in charge of setting the table for public debate—as often as not, it seems like they run in place trying to keep up—but the op-ed pages of The Wall Street Journal, The New York Times and (sometimes) The Washington Post throw their weight around with due cause. They represent the age-old structure of people with degrees sitting around and deciding what is right and what is wrong. What comes out from behind the closed-door meetings are unsigned editorials, the “voice and conscience” of a newspaper. The editorials are short, to the point and (in respectable cases) largely avoid the ad hominem attacks that subvert intelligent debate. We might not agree with them, but the best ones lay out a tight-knit, grounded argument.

To the general reading public, op-ed pages aren’t about unsigned editorials. No, it’s the other side of the op-ed page, the side with guest editorials and columnists—with their impossibly goofy headshots and total editorial freedom—that take public discourse to a highly caffeinated level. Guest editorials can feel like unmitigated cheap shots—“I can’t believe they let that idea get that kind of attention,” etc.—and columnists dish them out with seeming impunity. Each day witnesses a new domino effect of debate.

I worked at my school newspaper, The Michigan Daily, for a little over two years. In that time, I watched a variety of issues filter in and out of the op-ed pages there. Many students would tell you the Daily isn't held in high regard by the student body, evident in viral and vicious commentators heaping the bile and insults on our message boards. Letters to the editor were no different. Great umbrage was taken when a student group representing one side of an issue—say, the Middle East or affirmative action—was given the space to voice its opinion. That ire found its way into readers’ view of the paper itself. When the afflicted were given their chance in print, the other side hollered.

Further complicating this situation was the misunderstanding of the “wall” between the news and op-ed sections. Readers frequently dismissed the Daily’s well-reported stories as liberally biased since our op-ed page skewed that way. The New York Times caught a raft of shit for its February reporting on a potentially unethical relationship between Senator John McCain and a female lobbyist and many conservatives saw the article as perfectly in line with Times’ "liberal bias," that the paper was out to screw over McCain. Should op-ed pages run huge banners that explicitly explain how news and opinion are separated? Is the notion that many readers don't understand op-ed pages a "tough shit" scenario?

At times it’s fairly difficult—even for the discerning public—to not cry “partisan!” when a newspaper reports on divisive issues. Charges that the Daily was an irresponsible liberal rag were grounded in the fact that, yes, the paper is quite liberal (though the powers that be rebuffed my idea to print a whole issue on hemp paper). The fact remains that the editorial staff did make significant efforts to broaden its ideological output (with admittedly limited results). The news staff reported as fairly as it could, gaffes and all. What remained was a common misunderstanding of the lengths to which newspapers go to separate their news and op-ed staffs. One hundred percent impartiality is impossible to achieve. We're left with great news reporting subverted by negative opinion drummed up via inflammatory op-ed pages, as well as one-sided reporting overshadowing calm op-ed commentary.

Microsoft’s Steve Ballmer recently predicted that all things media will be solely on the Web by 2018. Newspapers as we know them will be dead. Whether it’ll be 2018 or 2019 or if you believe that prediction at all doesn’t matter: It’s time for op-ed pages to start rethinking how they approach public discourse, and the answer—of course—lies with the Internet. It's time for op-ed pages to break out of their exoskeletons of privilege. The platform of celebrity columnists dominating any given day of the week is antiquated. It speaks less to public debate and more to traditions of journalist laurels and pedigrees. Hyperbolically partisan voices only service the political sensation industry.

The page needs to open up: more voices, more point-counter point features, more diverse sourcing. Hard numbers, vetted facts and level arguments. Even if print is still around, stick the heavy-hitters on the Web and let the physical page operate with more nuanced debate. The big dailies certainly still have the clout to real in legitimate pundits for guest editorials—they need to take advantage of it. The machinery that churns out unsigned editorials has the right idea: present an idea as succinctly as possible. I'm not calling for an elimination of long-form commentary; I'm calling for op-ed pages to throw the rusty templates and take a different approach to public debate.

Stop endorsing candidates, stop allowing columnists to heap egotistical he-said-she-said elitism on English language enthusiasts. Understand that your time is waning with all print media; that if you do not evolve you will be devoured by the Internet or fade into irrelevancy. Take the clout you still have and hit the ground running: further blur online and print commentary, take note of how great blogs and Internet pubs aggregate disparate opinions and parse the intelligent, if still partisan, ones. Remake yourselves in the image of the public you wish to serve. Discerning readers can quickly find well-written rebuttals on the Net—sometimes better written and more nuanced than your columns.

Cut them off at the pass. Be the legit sounding boards you know you can be. The clock is ticking.

Elevating the Discourse

The problem with op-ed pages isn’t that they’re partisan, it’s that they don’t offer the Internet’s variety of voices and formats.

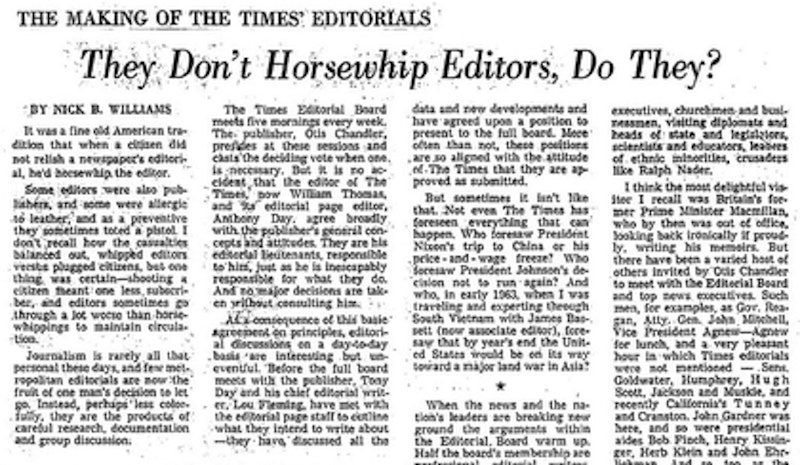

A Los Angeles Times op-ed piece from 1971.