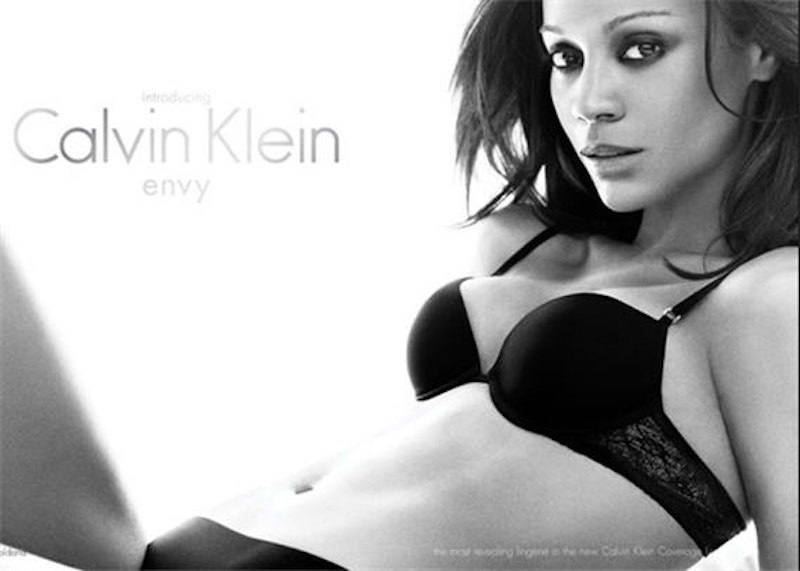

In a world where the prime-time television landscape is liberally splashed with enticements for Victoria’s Secret and vibrators—no, seriously—there is nothing inherently shocking or scandalous about Calvin Klein television advertisements for intriguingly named fragrances. These ponderous, black and white visual poems set tongues wagging even as they helped make stars out of everyone from Brooke Shields to Kate Moss to Mark Wahlberg. In our post-appalled, racy American Apparel ad-plastered epoch, it’s startling to see the ads make a return to the national scene—and it’s even more surprising that the camera’s subject is actress Zoe Saldana. Saldana’s Hollywood fame is, unquestionably, in a comfortable upward trajectory—she had a bit part in a Pirates of the Caribbean flick, then won secondary and starring roles in Star Trek and Avatar, respectively—but she’s yet to wrestle a part requiring melodic heavy-lifting. She’s exotic in an on-the-cusp-of-alluring, Rihanna way, not a round-the-way girl way: a beautifully telegenic cipher, whoever you want her to be, and as such the perfect post-racial go-to Glamazon for comic-book flicks.

The first time I watched Saldana’s Calvin Klein spot—for underwear, for a scent, for the overall CK brand, is there seriously a separation between these things anymore?—I couldn’t figure out why she signed on for it. Surely she didn’t need the money or the exposure; she just appeared in the highest-grossing movie ever made as a blue-skinned, nine-foot tall alien warrior princess.

It took watching the ad on YouTube a few times for me to understand her logic. Only then did I finally get it and realize why Saldana felt compelled to smile with a mixture of coyness and intimacy into America’s living rooms, to rolling about on a mattress in black lingerie as cameras lasciviously tracked every exposed inch of flesh, as white lights and fans lent the scene a sense of the ethereal, the fantastic. Saldana seized what struck her as an opportunity to introduce herself, to define and guide her public persona, to present “Zoe Saldana” as an actual person, a flesh and blood human being—not a cultural construct, a fetish object for super-geeks. "Whether the saucy innuendo about tattoos or Facebook-esque “openness”

was

dialogue-script hokum is totally beside the point; Saldana adroitly

harnessed

the power of advertising, via an established brand, to extend her

career possibilities and sidestep typecasting. (Not to mention deftly

deflecting the male gaze away from her flesh and, however briefly, into

her soul; I hear echoes, however faint, of the Halle Berry topless

scene in Swordfish.)" Why become the new Linda Cardinelli if you don’t have to?