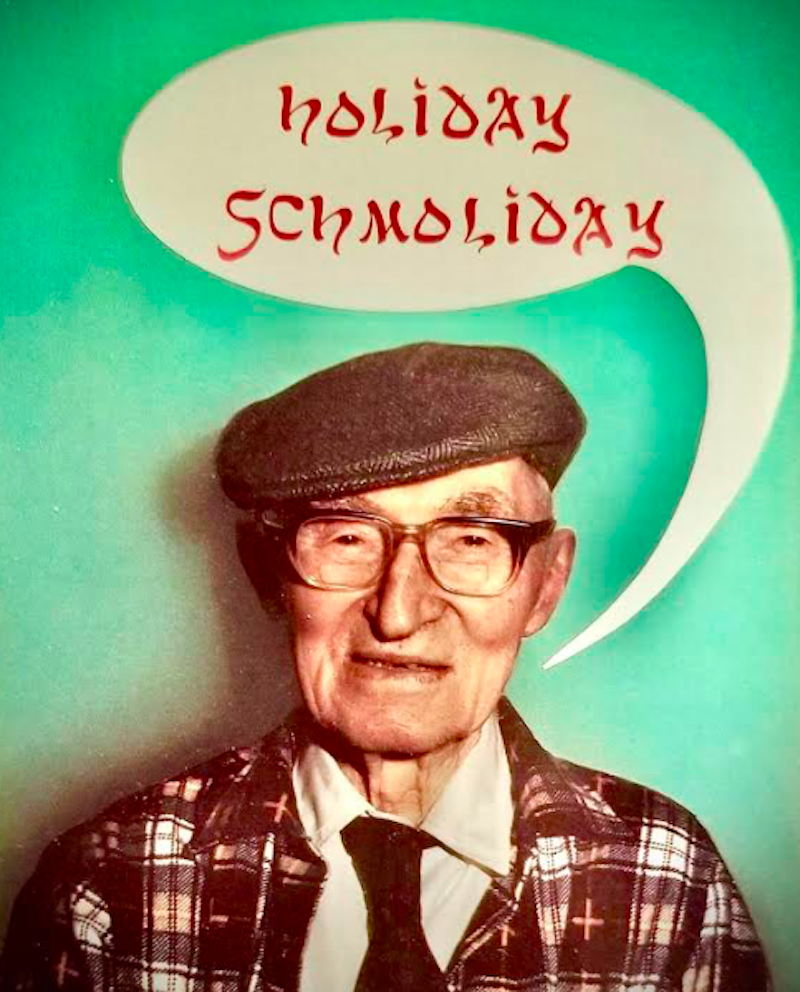

Born in Baltimore, quiet and contemplative as an owl, every morning newsstand owner Abe Sherman (1898-1987) squeezed a full lemon into a cup of hot water. He carefully stirred this citrus concoction sitting in his crow’s nest position overlooking Park Ave. near the bookstore door. The life-long newsboy started hawking papers at an early age in 1906.

His first newsstand opened in 1919, at the base of the Battle Monument in Baltimore on Calvert and Fayette Sts. Some critics disliked how drivers would circle their cars around when Sherman delivered newspapers. Politicians, attorneys, and celebrities alike, such as H.L. Mencken and F. Scott Fitzgerald, received the most recent news, rain or shine. Eventually, Baltimore City would ask him to relocate.

I saw an early advertisement for the news vendor showing traces of history, it read: “Sherman Bros. I will be pleased to leave you The News every evening. It is the only newspaper in Baltimore with The Associated Press. ONE CENT A COPY.”

Before a typical day started, Sherman would deliver worldly consul to his employees while sipping his drink. “If you do this every day, you’ll live forever. Now get that stack of papers out of the way.”

During the early-1980s, he was my boss. I worked at Sherman’s for a summer. Other colleagues who also worked there included artists Tom Chalkley and Bonnie Bonnell. When you got to know Sherman, you discovered a kind, old-school personality who could be just a bit grumpy at times. In the early-1970s, the lively, downtown retail market took a hit. Changes from redlining and blockbusting ravaged Baltimore. Antique, art and jewelry establishments could still be found along the Howard St. corridor. For Nehru shirts, bell bottoms, and assorted accessories you shopped over on Read St. at The Bead Experience, Middle Earth, The Clothes Horse and Omar’s Tent Factory.

The diverse Cathedral Hill/Chinatown neighborhood had headshops and boutiques too. The New Era Bookstore, Music Liberated and Body Furniture sat alongside the White Rice Inn on Park Ave. The old-fashioned Maison Marconi’s continental restaurant served oysters Pauline in a three-story townhouse where waiters wore tuxedos at 106 W. Saratoga St. Down the block at 114 W. Saratoga St. is the Shrine of Saint Alphonsus Liguori; Mass is still said there in Latin. These locations work as an invisible Southern perimeter.

Towards the north end on Mulberry St. next door to Brass Towne Antiques; a red, neon Chop Suey sign hung above a doorway entrance that announced the “up one flight of stairs” Mee Jun Low. Remember a cheap eggroll on a high school date served by the waitress Irene, you probably had it here.

In the early-20th century, the former jazz speakeasy that later became Martick’s Tyson Street Tavern was situated across the street at 214 Mulberry St. This location is a benchmark—a steadfast, countercultural enclave that cultivated the development of Baltimore’s bohemian identity. Maelcum Soul (1940-1968), a beatnik princess and early John Waters muse, worked at this address. After 1970, it became known as Martick’s Restaurant Francais. Legendary Morris Martick (1923-2011) was born in this building, he owned and operated an eclectic and unique restaurant until 2008. Almost every employee Morris hired within this snakeskin-walled establishment had some sort of association with the art world. Amazing how an entire neighborhood might pass for a unisex, retro-bohemian movie set.

Right in the middle of it all, Abe Sherman opened a new bookstore in 1970 on the southwest corner of Park Ave. and Mulberry St. close to Edgar Allan Poe’s grave on Paca and Fayette Sts. The building’s windows were plastered with large black and white posters featuring: the iconic, bombshell Raquel Welch in a fur hide bikini from One Million Years BC, Humphrey Bogart nursing a shot and W.C. Fields holding a deck of cards.

Sherman’s Book Store is where Tom DiVenti bought his first copy of Arthur Rimbaud’s poems. The pulp wonderland had “too many things of interest” with obscure music, film and art magazines. Stacked floor-to-ceiling; newspapers from around the world. Adult titles naturally, kept behind the cash register. His amiable son, Philip Sherman, a Baltimore attorney would check in regularly to see how things were going. With all the blacklight posters, incense, and love buttons, it’s hard to believe the store was owned by a dual World War Army veteran.

If you ever crossed paths with Sherman, you had the honor of being reprimanded by someone who fought with Maryland’s 175th Regiment on the shores of Normandy, and you deserve a victory lap. With the grit and gusto of a Samuel Fuller movie soldier, he’d bark out combat orders, “Com’n you bastards, let’s go!” The attack launched on the Germans earned him a Silver Star.

Sherman was a charming sage with vaudevillian wit and wisdom. He had a reputation of rankling more than a few customers. I got a real kick out of it every time he threw someone out of the store, and that was a lot. The place was tiny and cramped with two little aisles. It was easy for him to hover behind you. Like clockwork, I’d hear the classic raspy, one-liner: “There’s no reading here, library’s up the street,” referring to Enoch Pratt’s Central Library branch, a block east on Cathedral St.

Baltimore’s a town full of eccentric characters. Just based on the numbers, there’s always going to be some degree of connection. When Baltimore’s parade-loving crowds lined the city streets, a regular, flag-waving participant was politician Hyman A. Pressman (1914-1996.) He was also a poet. Pressman, once wrote a poem for Abe Sherman when Baltimore City requested his newsstand move to another corner:

This is truly beautiful, Abe,

Treat it tenderly, like a babe.

Protect it from all passing trucks.

It cost eleven thousand bucks.

In November 1964, Gunther Brewery helped Sherman’s new kiosk open in its original spot. The first newspaper sold was purchased by then-Mayor Theodore R. McKeldin with a borrowed dollar from an onlooker. As things change, let’s hope future Baltimore government decisions don’t end in a quagmire. That would not please Abe Sherman; a patriot, soldier, and philosopher.