(Ed: For context, please watch this video. Embedding was disabled, but the link will open in a new window).

NOT MY WILL, BUT THINE, BE DONE is the legend, in raised gold lettering, hovering above the pulpit at Victory Prayer Chapel. To call that passage “instructive” would be to court riotous understatement, black comedy, or some ghastly farce. There is no choice but to believe this; to disavow the truth behind those words is to surrender to the idea that what happens or doesn’t happen to us in this life is without any meaning whatsoever, without sense, without reason. Funerals don’t lend themselves well to narratives; it’s easier to understand or interpret them as floods of melancholy, of pathos, of detail that’s vivid or less so, depending on one’s degree of mourning.

It had been exactly a week, so I’d made peace with the shock, the spiraling chasm of disbelief that accompanied the news; within our family a grim stoicism reigned, with interruptions. Christopher’s Old Dominion classmates—they were legion, a credit to his impact as a human being—were less sanguine, astonished in their grief. One mourner had a raggedy Mohawk. Police orchestrated traffic at Victory and escorted us to the mausoleum. My uncle Elijah’s incisive eulogy struck me as appropriately unprofessional, unabashedly unemotional, all-inclusive: he helped us locate a meaning in my cousin’s life, find a joy in who he was and what he meant to us, a purpose, a positivity. The family posed for a photograph, and we were ordered to say “Chris!” instead of “cheese”—a new interfamilial meme. The press kept a respectful distance. We got lost on the way from the mausoleum and enjoyed an accidental tour of rowhouse Baltimore: tilted, tidy, block-like, bombed-out. Everyone asked after Nodin and Alecia; I displayed his pre-school graduation photograph with fatherly pride. When my mother wept during intense moments during the service, I held her close, draped in the Pronto Umo suit she bought me. The pastors and deacons officiating were the same ones who helped my grandmother run the chapel when I was a boy.

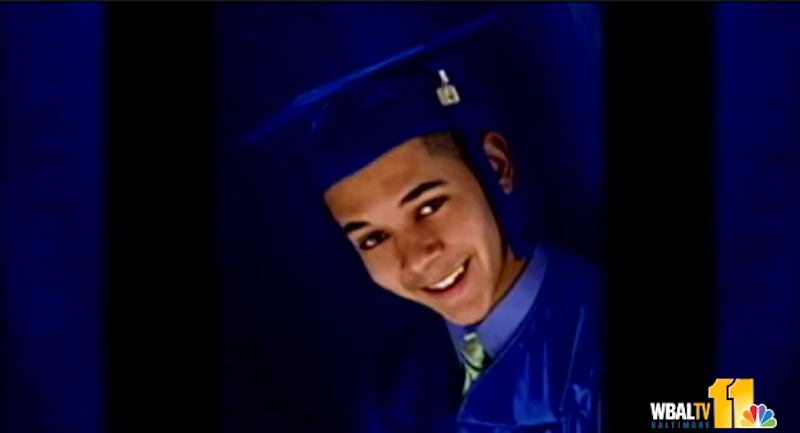

I didn’t know Christopher very well, I confess. Fourteen years of age separated us, a vast generational chasm, or maybe I’m just a bigger narcissist than I’m willing to admit. Which is to say that I can’t eulogize him properly, and I won’t try; dozens of people closer to him have already paid testament to what an amazing person, leader, and friend he was. As for me, I can remember him as a baby, as a boy, and as a teenager; just glimpses at holidays, caught in the flash of other people’s photographs.

In the early 00s, my father, Chris, his father, James, and I drove from Maryland to South Carolina for a weekend; the intent was to savor the open road, visit some sites of historical significance to our family, catch up with some distant relatives. Memories of that trip are a blur: questionable tales of family lore, decrepit headstones, gorging at Shoney’s, sweating plastic-encased furniture in someone’s living room, scribbling on postcards, joshing between my dad and my uncle, regional papers we picked up along the way. I’d recently acquired the two-disc version of Stephen Malkmus and The Jicks’ Pig Lib, and I listened to the second disc again and again, on a Discman loop: “Old Jerry,” “Fractions and Feelings,” “Dynamic Calories.” Chris, as I recall, occupied himself with some sort of hand-held video-game system. And we just didn’t talk to one another. At one point he reached out to me—I can’t remember what he wanted, perhaps he was inviting me to play something, but I blew him off. It was June. Almost exactly eight years later I gazed out of the window of a Southwest Airlines plane, watching the country flash by, the Jicks’ new Mirror Traffic lending the experience a welcome, anesthetizing warmth and an accusatory irony.

En route to the mausoleum: a cousin I hadn’t spoken to in years filled me in on her third-world PR career, then an education about psychotic second-graders and their unreasonable parents. Two cousins have followed in our grandmother’s footsteps and are budding ministers; sometimes when I look at them, they’re still the snot-nosed brats their older brother and I didn’t want to be back when we spent summer weekdays along Edmonson Ave. Various fault lines disappeared, or healed temporarily, but related intrigues buzzed in memory. Despite the heat the men donned their suits; some suits were formal, appropriate in a versatile way, but then some were like the “zoot suits” Spike Lee and Denzel Washington wore in Malcolm X, suits that dared.

My cousin Debbie wore eye-piercing pinks, with a head-wrap; she looked like she was on an expedition to India; my cousin Kevin, somewhere in Hawaii, didn’t answer his cell phone, but his voicemail was full. Condolences felt weak but maybe the point was to extend them. And the fragility of things revealed itself, and my father, wiping his forehead with a handkerchief, turned to me and said, “This gives you a whole new perspective on fatherhood, doesn’t it?” And I agreed, and accepted that our funerals are our reunions now. To my chagrin, I contemplated starting a Facebook page. There was a sense of inclusion and warmth and devastation, but an equal feeling of that familiar journalistic detachment, of observing someone else’s tragedy and empathizing from a slight remove. Same as it ever was, but at the same time totally different.