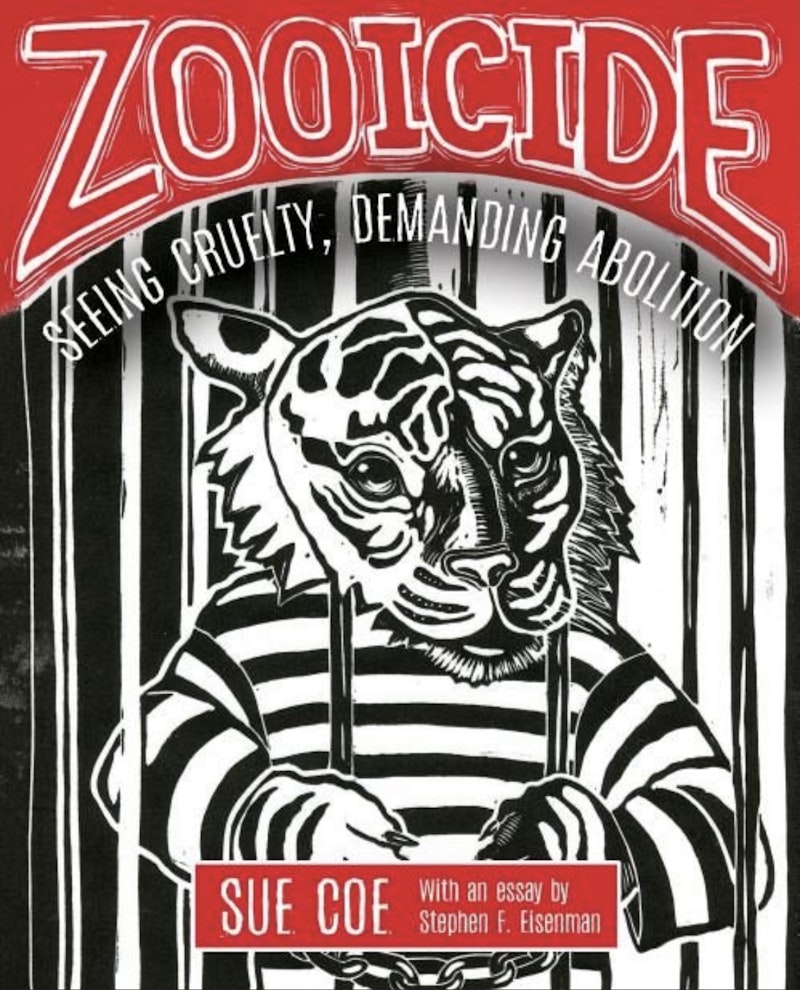

Zooicide: Seeing Cruelty, Demanding Abolition is a powerful collection of paintings and sketches from artist Sue Coe, depicting animals in captivity. It's hard to say you enjoy a book like this. The images and accompanying text are frequently disturbing. Still, the work is excellent and the reality is the suffering we inflict on animals in zoos is daunting.

Art historian Stephen F. Eisenman introduces the book with a semi-fictional essay written from the perspective of a vegan future. It details the evolution of the modern zoo, before assessing Coe's career. "She saw and depicted almost every horror visited upon animals in the conviction that cruelty must be witnessed and represented," Eisenman writes.

The images show a number of historical incidents. We see keepers poisoning or abandoning their animals in wartime. We see creatures escaping their enclosures and shot by police. But perhaps the most affecting pieces are the more mundane ones—despondent animals observed by humans from behind glass. I recently interviewed Coe about her work.

Splice Today: How did you decide to focus on animals in zoos?

Sue Coe: I’d done some drawings of Harambe—the gorilla who was shot by snipers when a child fell into his “enclosure”—which the publisher [AK Press] saw. They asked me to do a book. Zoos had killed Harambe's entire family. His mother and sister were accidentally gassed, so he was raised by a human keeper.

Every day another awful zoo atrocity appeared. Marius the giraffe was culled because he was an unwanted male. He was cut up and fed to lions, who were culled as well because they were surplus genetic material. A kangaroo was stoned to death because he or she wouldn’t jump. I also had a collection of older drawings from different events in which incarcerated animals had killed themselves or tried to escape.

ST: A number of paintings in this book depict historical scenes. What kind of research did you do for the project?

SC: I do forensic research for any project. Then I have to cast the words aside to make art. Sometimes an expert in the subject contacts me, as was the case with the “faithful elephants” who starved to death in a Tokyo zoo during World War II. A research librarian, working in Germany, contacted me. He had accumulated data on those elephants and could translate Japanese source material that went beyond anything I could discover.

ST: How many zoos did you visit while working on this book? Did you ever feel conflicted about supporting these institutions with your entrance fees or were you confident the trade-off was worth it?

SC: I used to travel for teaching and visited a zoo everywhere I went. After a while, they become depressingly identical. All traffic is routed through the gift stores and cafes. The wealthy oligarchs and corporations stamp their names on the cages. I must witness with my own eyes to challenge my own assumptions and to see through the animals' eyes—if possible. I'm never confident the trade-off is worth it. If anyone who sees these drawings decides to continue frequenting zoos, then I’ve failed as an artist.

ST: What are you working on now?

SC: I've been working on pieces related to President Trump and his enablers for the last four years. I’m a social political artist with a preference for covering animals. However, Trump has required my attention. He’s leaving office, but the strains of fascism that created him still exist. In the future, I plan to explore zoonotic viruses in my work more.