Last Sunday, at the stalwart Charles Theatre in Baltimore, before the main attraction of the excellent Bill Nighy vehicle Living—my son’s review—I saw a trailer for the current documentary Turn Every Page, an account of the 50-year working relationship between author Robert Caro and editor Robert Gottlieb (whose daughter Lizzie directed the movie). I’ve read all four volumes of Caro’s LBJ biography series, enjoyed them greatly, but like many have doubts that the historian, now 87, will finish it off. I hope he does—although the actuarial realties aren’t in his favor—since the fourth volume (2012), The Passage of Power, left off at the beginning of Johnson’s tumultuous presidency, just before the payoff is set to get rolling. Caro’s painstaking detail of Johnson’s life before he became president is marvelous, and believable (if from a liberal slant). But. What was LBJ thinking in, say, 1966, when he was ramping up the Vietnam War, taking weekly potshots from arch-rival Bobby Kennedy and other dovish Democrats who railed against the war, and, much to Johnson’s anger, put his civil rights and immigration achievements in the rear-view mirror? How did Lady Bird react to the ubiquitous taunts of “Hey, hey, LBJ, how many kids did you kill today?” I remember those years clearly, even as a teen, and would love to read Caro’s 800 pages. We’ll see.

That brought to mind a recent column in the U.K.’s Spectator by my old friend Taki, who, at 86, still meets his deadlines and might continue that pace until he’s 107. I wrote about Taki in this space a couple of years ago, which he probably didn’t see since, as detailed in the “Speccie” column, he leads an “unplugged” digital life. Nevertheless, he was complimentary about our association more than two decades ago.

He writes: “I think I was the last one to switch to writing on a word processor… when I founded ‘Taki’s Top Drawer’ for a New York weekly. The Bagel weekly was New York Press, and it was run by two of the best Americans in general and writers in particular I ever met, Russ Smith and John Strausbaugh… The editors’ only defect was that they did not accept typed copy delivered by fax. I had to learn to write on a computer.”

Taki’s praise of NYP is overly generous, typical of this well-mannered man, and appreciated, but we remember the issue of how copy was “accepted” differently. As I recall, although by 1998 every writer for the paper—with the exception of over-the-transom submissions—either emailed or dropped by a floppy disc containing their latest, we were so keen on Taki contributing that he could’ve dictated his 750 words. (It didn’t hurt that Taki refused to accept a fee for his efforts and, in fact, paid out of his own pocket for the men and women who comprised the “Top Drawer.”) In addition, at that period, the late-90s, NYP received more than 50 Letters to the Editor each week, and I know that those missives, mostly negative, came by fax or hand-delivery, were typed or hand-written, because the receptionist/keypuncher at the time would, after a few pints after work, complain about the backward process.

One more very Taki excerpt from his column about his internet-free life: “Recently the wife sent me some pictures on my mobile [which he says he never uses when a landline’s available] of my two angelic blond grandchildren, aged 2 and 3, frolicking naked on the beach, and when I went to a Bagel Apple store to learn how to open it, the man gave me a dirty look. I told him he had a filthy mind and who the seraphs were, but he looked unconvinced. But what did I expect in the Bagel, a place where sexual miscreants vastly outnumber normal folk?”

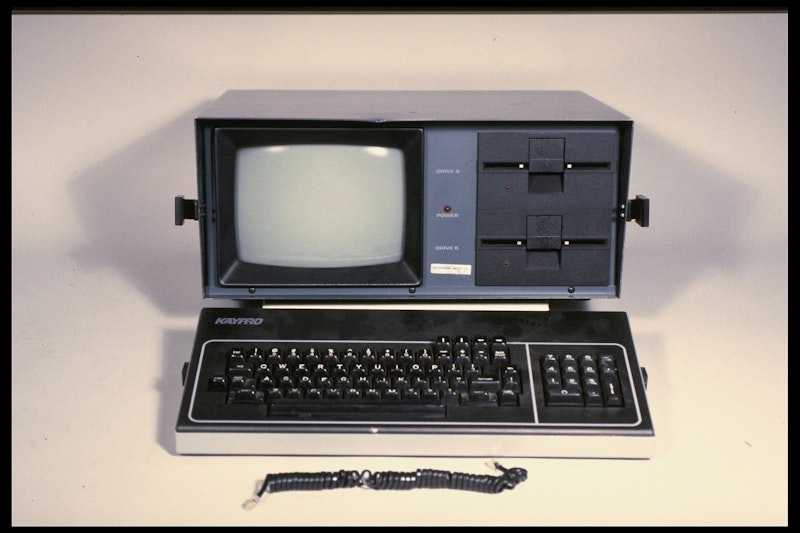

As it happened, earlier last week my son Nicky asked, in a general conversation about tech and writing, when I retired my portable Olivetti. He was somewhat surprised that that event occurred in the spring of 1986, when my business partner at City Paper sensibly bought a bunch of clunky, and large, Kaypro computers for the editorial staff, mostly to make the life of our typesetters easier (and cut down on their hours!). Like Taki, I was hesitant at first, and it was two months before my colleague and close friend Phyllis Orrick took me aside, and sternly said, “It’s time, Russ. No more white-out or scribbled corrections, and let me be the first to welcome you to the 1980s.”

It was a grueling two-hour tutorial, and though I grumbled, the ability to move blocks of text around, and, most importantly, not have to re-type a story three times, was nothing short of flabbergasting. That’s likely incomprehensible to younger people today, and quaint to those in my age bracket, but it was pretty incredible, especially at a time when Concorde appeared to be the vanguard of air travel, plans for bullet trains in the U.S. were in the news, and Craigslist had many years yet before it destroyed the cash-cow classifieds sections of weekly newspapers. Airline and train travel has become much worse since the 1980s—a fact that would’ve raised eyebrows back then—and the internet has mostly ruined newspapers, but composing on a computer rather than typewriter is still the very best.

•••

The best short story I’ve read in a long time comes from Homesickness, Irish writer Colin Barrett’s second collection. “The 10” is the final story in Homesickness, and is mostly about Danny Faulkner, 18, who lives on the West coast of Ireland, works at his father’s Nissan dealership, and has an on-again, off-again girlfriend in Shauna, who’s on the prowl for someone a bit more lively. Danny doesn’t drink, is outwardly happy-go-lucky, modest, and close to his father JJ and older brother Jeff. But Barrett leaves the reader up in the air about Danny’s fate, for he was once a can’t-miss football prospect who spent three years in Manchester training for a shot at landing with a pro team.

He writes: “The day he was cut loose by United was the day Danny decided he was done with football, and he was still done with it, because it was an awful thing, maybe the worst thing, to discover that in the end you were only good enough to get far enough to find out that you were not good enough.”

That’s one hell of a sentence, conveying so much about Danny in particular, and millions of people in general, in just 59 words. “The 10” stands out in Homesickness—all the stories are very good—because there’s not as much action, is far less ribald, just scattered drunken boasts and not nearly as much habitual promiscuity. Maybe that’s why it concluded the brief collection.

—Follow Russ Smith on Twitter: @MUGGER1955