By 1962, I had a song and dance act consisting of show tunes from Broadway musicals and Sinatra tunes. I was performing at mob joints all over Philadelphia, eventually taking the stage at the opulent Academy of Music with Jimmy Durante in a classic Vaudeville rendition of “Me And My Shadow.” I got an agent and had my first major audition in New York for the film version of The Sound of Music in front of Richard and Daryl Zanuck. I came in at #2 for one of the kids. Not a win, but a damned good showing for my first time out.

I did a lot of television commercials, auditioning for the Mad Men at J. Walter Thompson (Nixon hatchet-man H.R. Haldeman worked there at the time) and BBDO. Mad Men did nail the culture of Madison Avenue in the 60s. In 1964, I auditioned for the role of Nick in the London production of Herb Gardner’s A Thousand Clowns and was selected by the author himself who loudly proclaimed, “This kid is Nick!” Unfortunately, British child labor laws and British Equity prohibited me from performing there, but Gardner got me into two summer stock productions of the show, a short tour with Macdonald Carey, whom I never really connected with owing to the fact that he was drunk most of the time, and a good long tour with James Whitmore, one of the most talented, generous, and down-to-earth individuals I’ve ever met. We really connected. There’s a moment in the show where Nick and his Uncle Murray bust out ukuleles and perform the old Vaudeville number “Yes Sir, That’s My Baby.” I’ve never had more fun than performing that song with Jim Whitmore night after night. Robert Ryan directed that show. He was one of the funniest men I ever met, and he could hold his drink as well as any man I’ve ever met.

I did an episode of The Patty Duke Show and a boatload of TV commercials. In 1965, I did an Industrial show for Royal Crown Cola at the Fontainebleau Hotel in Miami. I spent that summer touring with Tom Ewell and Ludi Claire in a stock production of Life With Father. Michael Kahn cast me in his well-received off-Broadway production of Thornton Wilder’s The Happy Journey to Trenton and Camden at the Cherry Lane Theatre, produced by Wilder, Richard Barr, and Edward Albee. Albee made a lasting impression on me. I was awed by his quiet power over the other adults. They were very cautious around him, as if there were some coiled menace ready to strike just beneath his polished and suave exterior, which, of course, during his drinking days, there was. That’s probably why he quit.

I had my Broadway moment in the Lincoln Center Repertory Theatre’s production of Bertolt Brecht’s Galileo, opposite Anthony Quayle. To give the actors ground for the story, director Michael Hirsch showed us the full film footage of the McCarthy hearings, which made a strong and indelible impression on me. My agent informed my mother and me that the next step in my career should be a move to Hollywood.

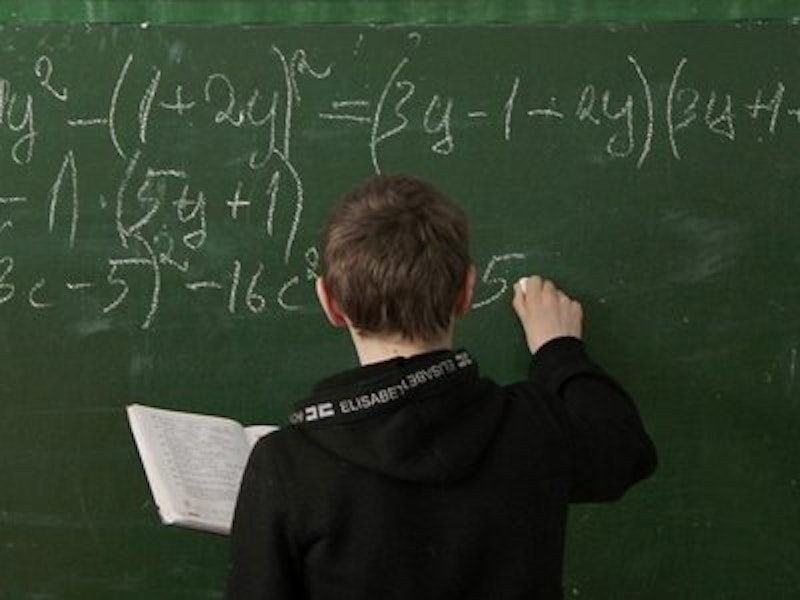

And then it all vanished. I was attending the Mace School for Professional Children on W. 71st St. I flunked eighth-grade algebra. My adoptive parents were still engaged in a divorce action initiated by my mother in 1956. Custody of me was a big issue. My father seized upon my algebra failure as evidence that acting was interfering with my education, calling into question my mother’s fitness as a guardian. For her part, she didn’t want to jeopardize any possible settlement in her favor by moving to California.

Against the advice of every other adult in my life, she pulled us out of New York and back to Camden, New Jersey. I couldn’t begin to grasp it. I was functioning as an adult, working full-time, a member of two unions, and was dragged back to Camden because of algebra.

I’ve never in my adult life used algebra. I did learn a valuable lesson about hard work, though: it doesn’t matter. You can’t win.