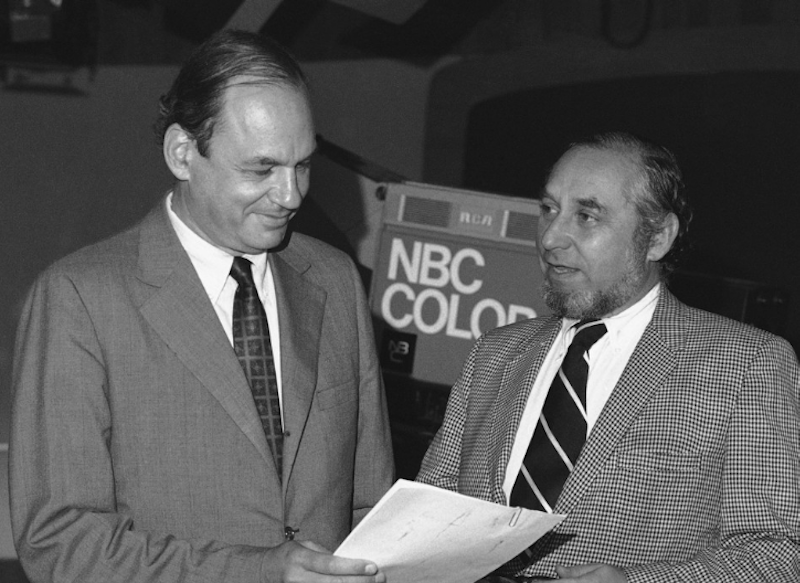

The truth is, I don’t mind uptight, right on, or chicken out. Nor do I mind can of worms, whole new ball game, carrying water, bottom line, or playing hardball. All these were held up for ridicule by a runaway best-seller of 1974, the brief and stylish volume entitled Strictly Speaking. It was written by a TV newsman of the type then described as tart-tongued and/or gimlet-eyed, and it deplored “the sad state of language,” warning us that “language is in decline.” Grudgingly, I concede that the author, Edwin Newman, knew how to write. But I’d say he missed the mark regarding every phrase listed here. I bet I’ve used most of them and I don’t mind any.

I might use marathon too. “Marathon talks are a relatively new development in labor negotiations,” writes Newman, feeling puckish. “As the representatives of employer and union pound along, gasping out proposals about wage differentials and grievance procedures, and accusing each other of not engaging in genuine collective bargaining, the virtue of marathon talks becomes clear. It is that the parties quickly tire of the pace and, rather than go on running, come to an agreement.” The joke is that a marathon, by definition, involves running, so the negotiators must be running. Huh. I’d say that marathon is a handy way of referring to a prolonged bout of some given activity, a bout that must continue until physical hardship threatens or arrives. Marathon negotiations don’t have to involve sweat socks and running shorts, and a Wagnerian accent need not originate with anybody named Wagner. I make this second point because at one point Newman refers to “a Wagnerian accent” when he means a German accent. If Wagnerian can mean German, then marathon need not hang back and be shy.

Admittedly, I hold a grudge against Newman. I had a boss I disliked, and one day he announced that he’d been reading Strictly Speaking again and it held up, and there you go. Let me expand on that. Like my boss, Strictly Speaking tends toward a simple-minded brand of smart-guy self-amusement. The book ignores facts so that it can marvel at manufactured absurdity. I point to Newman’s discussion of the “bonnie baby” question. British politicians used to campaign on promises of “bonnie babies” and “bonnier babies,” and Newman has lengthy fun with this: “The party in power claimed that the babies of the country had never been so bonnie, thanks to the enlightened policies of the party in power, while the opposition party claimed,” etc.

I scoff at Newman. The Brits conscripted during the world wars were shockingly undernourished; so was much of the country. Britons grew longer legs, wider shoulders, and squarer jaws because the government (following a peaceful revolution by popular vote) finally decided to bring nutrition within reach of the population. I know this from the class I took long ago on 20th-century Britain, and from seeing specimens of various Brits over the years.

When Newman heard the politicians talking about “bonnie,” he must’ve known why they were talking. One party was saying that at last Britain would give every child the same shot at a healthy life. The other party was saying that, yes, Britain certainly would, and that the second party was the one to do it. The politicians may sometimes have talked about “no more underweight babies” or “no more babies at risk of mental deficiency.” But to be briefer and more pleasant, they hit on a term of art: “bonnie babies.” That’s a contrived phrase, and its fad may count as a curiosity. (Who would ever say “bonnie baby” except under frightful socio-historic force of circumstance?) But it wasn’t absurd behavior, not unless you leave out everything except the bare fact of the phrase leaving a politician’s mouth.

Yet Newman was a talented man. His brisk, inventive, well-sounded prose becomes unclear only when his transition sentences contort themselves. This is the cost of loading together topics like an after-dinner speaker. As a TV personality, Newman may have been touring the dinner circuit; if so, I bet he earned his money. But, again if so, Strictly Speaking betrays an unhealthy influence. It’s a stream of anecdotes and opinions that would need to work its way up to be disjointed. This fact seems especially poor when viewed against the book’s pretensions. Newman, or his editors, carry on as if he’d written an unsparing look at a topic, namely the sloppifying and mushifying of language and what these things have done to us. The book is more like Goofy Things People Do With Words, Plus Other Goofy Things I’ve Seen in My Time.

The 1970s were a great decade for language scolds. Newman’s book was followed by many, all of them deploring the culture’s post-hippie linguistic casualness, the spread of bureaucratese, the plague of p.r. speak, and so on. Being vapid and slovenly was the new norm, and the language cops stood against the norm. Their means of doing so was to make a fuss about dangling modifiers and the use of hopefully. Almost half a century has passed. Were they right? We sure wound up in a vapid and slovenly mess, what with these being the Trump years. Even so, Newman was wrong about chicken out and the others.

—Follow C.T. May on Twitter: @CTMay3